Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit Prince’s best album of the ’90s, a funked-out opus mired in extra-musical drama.

The first half of the 1990s was a frantically productive time for Prince. After stumbling out of the gate with the disastrous Graffiti Bridge movie, over the next five years he released five albums, toured extensively, opened (and frequently performed at) his own chain of nightclubs, closed one record label and created another, issued a groundbreaking interactive CD-ROM and a longform home video, launched two self-published magazines, worked with the Joffrey Ballet on a piece set to his music, and claimed his first-ever No. 1 single in the UK.

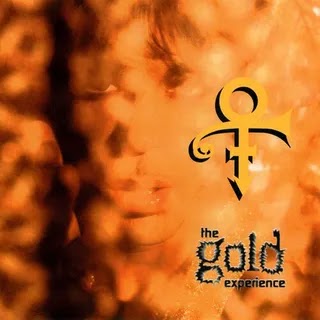

On June 7, 1993—his 35th birthday—Prince informed the world that he was now to be known as an unpronounceable symbol that, in one form or another, had entered his iconography in recent years. (It was the title of his previous album, generally referred to as the “Love Symbol” album and he had been signing autographs with the mark for some time.) People went nuts: Was it a joke? A scam? How could he have a name that no one could say? Hadn’t he gone far enough already with all those silly “2”s and “U”s instead of real words in his titles? The greatest artist of his generation immediately became a punchline.

With the announcement came a proclamation that The Artist Formerly Known as Prince (the nomenclature that many settled on) would no longer be performing any of his old songs, as they belonged to the old name. Having already asserted, about six weeks earlier, that he was retiring from studio recording, many speculated that the name change was an attempt to finesse his way out of his contract with Warner Bros.—a deal he had signed less than a year earlier, with a potential payout of $100 million that was trumpeted as the biggest in history. And largely lost in all of this confusion was The Gold Experience—Prince’s finest album of the decade, an imperfect but rewarding record that became a casualty of extra-musical drama.

I had a front-row view of this dizzying era in Prince’s career. In early 1993, I reviewed the opening of the Act I tour for Rolling Stone and received word that he wanted to meet me. We spent the next year getting together off-and-on—in San Francisco, New York, at Paisley Park—before he agreed to an interview for Vibe magazine (where I was then working), his first time going on the record in print in almost five years.

We convened in Monte Carlo in May 1994; he was parked there for several days to receive honors at the World Music Awards. He spoke at length about his frustration at not being able to release music when and how he wanted to, how Warner Bros. couldn’t keep up with his output; soon he would be writing the word “slave” on his cheek in more provocative protest. He was also surprisingly thoughtful and serious regarding the name change.

“It’s fun to draw a line in the sand and say, ‘Things change here,’” he said during rehearsal, backstage at the Monte Carlo Sporting Club. “I don’t mind if people are cynical or make jokes—that’s part of it, but this is what I choose to be called. You find out quickly who respects and who disrespects you. It took Muhammad Ali years before people stopped calling him Cassius Clay.”

Back in his room at the historic Hotel de Paris, overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, Prince played me portions of two albums in progress—one, titled Come, would carry the old name, and the other, then called The Gold Album, would be released under the new moniker. At the time, Come struck me as a solid, unsurprising Prince record (whatever that means), while The Gold Album felt looser, more exciting and experimental, which he was visibly more enthusiastic about.

Come was released a few months later—with a cover shot at a cemetery and emblazoned with the words “Prince 1958-1993”—to general disinterest. But it would be almost a year and a half until the other record, eventually renamed The Gold Experience, finally surfaced.

The truth is, The Gold Experience never had a chance. Prince held the album hostage in his negotiations with Warner Bros., telling the press that “it’s the best album I’ve ever made, but it probably won’t come out” and projecting the cover image behind him at live shows with the words “Release: Never.” Though he was playing much of the material in concert, by the time the record came out in September 1995, the myth around it had created impossible expectations.

Listening with some distance from the narrative—or for the first time—reveals a musician rediscovering his extraordinary power, his unparalleled ability to synthesize genres and styles and then flawlessly execute his musical vision. The album displays range from slow-jam ballads (“Shhh,” which he had previously given to young singer Tevin Campbell, who had a Top 10 R&B hit with it, and “Eye Hate U”) to the glam-rock kick of “Endorphinmachine” and shimmering power pop of “Dolphin.” No one else had the tools that Prince commanded, but it had been a while since he put them to good use.

One anchor is the featherlight, Philly-soul-style “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World”—which had been a Top 5 hit in early 1994 when Prince released it on the independent Bellmark label—but the album is otherwise heavy on the funk: The swinging horns on “Billy Jack Bitch” and the loopy groove of “Now” offer some of the set’s finer, under-appreciated highlights. (Most of the material was recorded in late 1993 and early 1994, and the song selection changed many times; the version I heard in Monaco contained the loping, bass-heavy live favorite “Days of Wild” and the extremely raunchy reggae jam “Ripopgodazippa,” which would have made things even funkier.)

Prince also reconnects with the guitar on the album after a few years of wilful restraint. He flashes his Eddie Van Halen-level chops on “Endorphinmachine” and the concluding “Gold,” a big swing of a power ballad that’s a bit too corny and obvious to reach the peaks of “Purple Rain.” Clocking in at over an hour, The Gold Experience starts to drag in spots, but moments like the carnal, metallic punch of “319” (first heard in the notorious so-terrible-it’s-delicious movie Showgirls!) stand with his best.

After reconfiguring the rock-based Revolution on Sign o’ the Times in 1987, Prince expanded his touring band to bring in horns and additional musicians on the magnificent Lovesexy shows. Since introducing the New Power Generation (NPG) on Diamonds and Pearls (1991), he had maintained the larger arrangements but skewed more toward groove. On this album and the live shows that led to it, the sound was stripped back to a harder-edged slam.

“The Lovesexy band was about musicality, a willingness to take risks,” Prince told me in Monaco. “Since then I’ve been thinking too much. This band is about funk, so I’ve learned to get out of the way and let that be the sound, the look, the style, everything.” (When we first met and he brought me onstage during soundcheck, he said, “I love this band, I just wish they were all girls.”)

Prince wasn’t only fighting with his label during the ’90s; he was battling hip-hop, the new, dominant form of Black pop music. For someone raised with such a strong commitment to musicianship, and so superhuman in both talent and discipline, the move away from instrumentation, chords, and melody was clearly confusing: He worked with such giants as Chuck D and Ice Cube (and toward the end of his life was in communication with Kendrick Lamar) but most of his attempts to bring hip-hop into his own music involved grafting the pedestrian Tony M onto the NPG for nonsense like “Jughead.”

On The Gold Experience, Prince finally reaches some kind of peace with hip-hop. In Rolling Stone, Carol Cooper perceptively noted that “as usual, the attempts at rap come off as part satire and part celebration of the form.” But the spoken word flow on “P. Control” and the (admittedly already dated) new jack swing-y beat of “We March” are examples of actually integrating the new form, using it for a purpose rather than just out of some sense of obligation to a young audience.

Speaking of new forms, The Gold Experience is presented as a mock virtual reality trip, with keyboard clicks and a robotic female voice introducing some of the songs (“This experience will cover courtship, sex, commitment, fetishes, loneliness, vindication, love, and hate”). It’s awkward but ahead of its time, and illustrates how Prince’s love/hate relationship with technology—like his battles with his record company—could be prophetic. “Once the Internet is a reality, the music business is finished,” he told London’s Evening Standard in 1995, four years before Napster.

Not surprisingly, the unifying theme that lurks within the lyrics of The Gold Experience is freedom. Sexual freedom, of course, had always been present for him, but other expressions of liberation appear throughout: creative control (“You can cut off all my fins/But to your ways I will not bend/I’ll die before I let you tell me how to swim” in “Dolphin”), political protest (“We March”), even feminism. “P. Control”—“Pussy Control,” until Prince was told stores wouldn’t stock a record printed with that title—is clunky and easily misread; one review called it the album’s “weakest, most juvenile and most sexist track.” But the subject is a successful businesswoman who turns down a rapper when he asks her to sing on his track, saying “You could go platinum four times/Still couldn’t make what I make in a week.”

The story of Prince’s career—well, a story, at least—is the tension between his desires for the freedom of a cult artist and the popularity of a rock star. “The thing the public has to understand is he’s done the big thing, the ‘Purple Rain’ thing,” NPG guitarist Levi Seacer said in 1993. “He’s seen those big sales and been on top of the world. But an artist has to be able to grow, feel like they’re moving forward. You have to let the artist keep going or they’ll die.”

The Gold Experience feels like the last time Prince, or The Artist Formally Known as Prince, tried to walk that tightrope, doing weird stuff like “Shy,” a dreamy tale of a female gang member, or the unhinged vocal on “Now,” while still assuming the pop audience would follow him. Soon, these directions would bifurcate: on the one side, the cynical, Santana-style all-star-guest strategy of Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic or the calculated throwback sound of Musicology, and on the other, five-CD box sets and instrumental or religious-themed albums.

So even though The Gold Experience was the first release under a new name, it was really the end of an era. By the time the album came out, almost two years after recording began, The Artist Formerly Known as Prince seemed bored with it and didn’t do much to promote its success. It climbed to No. 6 on the charts anyway, and picked up its gold certification. Prince found his way out of his Warner Bros. contract and moved on to other matters.

But in the middle of the maelstrom, there was a time when the fate of The Gold Experience felt critical. “People think that this is all some scheme,” he told me back in 1994, while people were losing their minds over the notion that he had lost his mind. “I don’t have a master plan; maybe somebody does.”

That didn’t make his intentions any less serious, though. “There’s no reason for me to be playing around now,” the once and future Prince said with a laugh. “Now we’re just doing things for the funk of it.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment