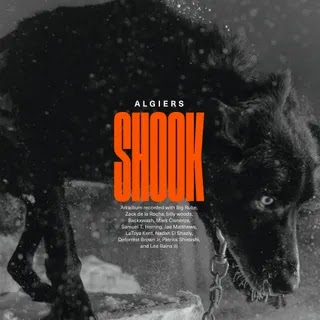

With a crew of equally radical peers in tow, the Atlanta band’s new album is a dissonant but hopeful statement about dreaming up a better world.

Algiers’ politics are not subtle: For starters, they draw their name from a place once at the heart of the anti-colonial struggle. The Atlanta band’s lyrics are staunchly anti-capitalist, fueled by the righteous anger of people who know exactly how we got here and who’s to blame. Moreover, frontperson Franklin James Fisher is hyper-aware of his place as a Black frontman in a white industry—and of how the band’s values inform the way they’re perceived. While their debut was tight and focused, the group has sometimes buckled under the weight of their own bombast, hunched like Atlas as they carry a burden so great it threatens to crush them. But Shook, while characteristically dark and deadly serious, feels different. It’s a record built around community, evidence that when the struggle is shared with like-minded peers, it feels lighter. So does the music.

The group draws from an eclectic palette (gospel, blues, rap, jazz, R&B, metal, spoken word), creating a chaotic patchwork underpinned by industrial drums and synths. As influences, they cite producers DJ Premier and DJ Screw; first-wave New York punks Dead Boys; East Berlin post-punks Dïat; Memphis MC Lukah; and the rappers of Buffalo, NY crew Griselda. It’s intentionally disparate, but you can see where the dots connect: The way Premier and Screw used wildly different ways to manipulate previously recorded material; both the New York and German bands’ sneering tone, which drips with sarcasm; and the outsider ethos of rappers spiritually connected to New York City, even if they’re physically distant from it. It’s difficult to pinpoint, but these ostensibly paradoxical legacies intertwine all throughout Shook.

The characters that populate the album help narrow the scope of their rage, zooming in on individual perspectives and experiences. When the rapper-producer Backxwash raps, “The news said I was looney/Till poof, happens to you” on “Bite Back,” she does so in a world that seeks to criminalize her existence, in a verse that leans heavily on the infamous manhunt of former LAPD officer Christopher Dorner. When Rage Against the Machine’s Zack de la Rocha barks, “What it be, God?/No rehab for my jihad” on “Irreversible Damage,” he does so from the heart of his band’s radical ethos.

Yet no figure has as much influence on the overarching message of the LP as Big Rube, the spoken word poet best known for his Dungeon Family affiliation and his narration on classic OutKast records. The rumbling bass tones of Rube’s voice, which are peppered throughout the album, instantly lend Shook a strong sense of place, declaring from jump that this record is a product of Atlanta. And there’s a gentleness to his speech, its weathered texture hinting at hardships endured. He serves as the record’s—and in some ways, the city’s—conscience, the wise old uncle willing to give you the unvarnished truth.

The themes on Shook are often bleak. But wherever there is struggle, there is also joy. The skit “Comment #2” features the activist An Do, who speaks about how marginalized communities struggle to be seen outside of the context of their oppression. When your experience of pleasure is erased, and your identity reduced to your most tragic moments, your status as “other” is solidified. Still, there’s not much handholding here—listening to Shook, it can be difficult to find moments of levity amid the suffering and rage. Instead, its brief buoyancy is camouflaged: Consider the battered optimism of the instrumental breakdown on “Irreversible Damage” (“That’s what hope sounds like in 2022 when everything’s falling apart,” Fisher said in a statement upon the song’s release), or the “brown skin shining against the sun” in LaToya Kent’s poetic performance on “Born.”

That said, the group sounds most natural at their darkest—the reverbed growl of guitars, the synths colored with dirt and grime. They benefit from Matt Tong’s virtuosic drumming, which feels looser and more alive than any drum machine. While much of their early work stuck closely to standard pop song structures, they seem less restricted by convention than ever, building on the sound collages found on their tour mixtapes and one-off projects, like “Can the Sub Bass Speak?” (a reference to the foundational Gayatri Spivak essay). The Mark Cisneros collaboration “Out of Style Tragedy,” which starts with Fisher’s spoken word over a Sun Ra refrain, layers sample after sample until it unravels into dissonant noise. The link to Shook World, the mixtape that collaborator King Vision Ultra crafted from the album’s stems, is clear. Though Shook World’s raw, freewheeling structure often veers into the chaotic, ironically, the individual pieces that comprise Shook come into focus once deconstructed from their final form. Fisher’s words never ring clearer than when they’re cutting through the cacophony.

An Algiers record often requires some heavy lifting in order for the listener to fully engage. Usually, it’s easier to fit the pieces together if you’re familiar with the political references, or if you’ve already been living under colonialism’s yolk. But Shook feels more urgent, more arresting, with performances that draw you into their world. In part, it’s because the band has become a conduit for the community they’ve built, their work elevated by their own mutual admiration society. If we are indeed the company we keep, the Algiers coalition is strong, talented, and not about to go down quietly.

%20Music%20Album%20Reviews.webp)

0 comments:

Post a Comment