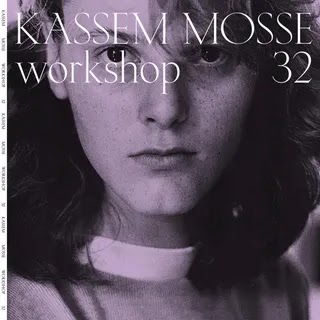

German deep-house technician Gunnar Wendel’s new album for the Workshop label clears away the murk of his early work, achieving disorienting effects with its oddly pristine palette.

Long before “lo-fi house” was blowing up play counts on YouTube, Kassem Mosse, aka Gunnar Wendel, was making hazy, low-visibility house jams that seemed to creep through a sooty midnight fog. Tarnished and corroded, betraying hints of line noise and vinyl hiss, his music sounded like he’d made it on machines that had lain buried for a decade in the dirt. It wasn’t just the omnipresent murk that made his tracks distinctive; it was the ominous, ungainly way they moved, skulking heavily around the edges of the dancefloor like a hunched beast lurking in the underbrush. At once sensual and sullen, it was a vision of club music charged with danger—a kind of inclement weather that could turn nasty at any minute.

Wendel was prolific in the late 2000s and early 2010s, but he slowed his output after 2016, around the same time that he began moving away from the dancefloor. That year’s Disclosure, for London label Honest Jon’s, was chilly and aloof, draping atonal synth loops over brittle machine beats. The following year’s Chilazon Gaiden, for his own Ominira imprint, was more energetic but nearly as forbidding; its speedy, spaced-out techno suggested an unheated warehouse rave in deep winter. workshop 32 is his first solo work as Kassem Mosse in six years, and it is his most immediate and enveloping release in ages. (Like all of his releases on Lowtec’s Workshop label, its catalog number doubles as its title.)

This isn’t the Kassem Mosse palette of yore. He’s vacuumed up the muck, swept away the cobwebs, and even air-dusted the faders on his mixing desk, from the sound of things. His synths have the airy quality of wind chimes, and his pristine, undistorted drums sit like islands in a sea of empty space; the stereo panning is so disconcertingly precise, a bat could echolocate each tom, snare, and clap. Still, barring the odd wash of warmly nostalgic pads, a sense of emotional blankness prevails. No matter how physically engaging these tracks may be, they maintain a stone-faced remove.

At times, the mood is downright unsettling. Competing polyrhythms resist parsing; the occasional burst of out-of-sync beats suggests a DJ losing control of the mix. Synths throw off icy dissonance. “D1” (as is typical for Workshop releases, all but one of the tracks are titled only by their position on the vinyl) is set against a high-pitched whine that rises and falls like wind whistling through the window frame.

Very little actually happens in these arrangements. Each track offers just a handful of sounds—truncated drum hits and ribbons of synth, but also scraps of background noise, speaking voices, and sourceless clatter—that spin as elegantly, and ceaselessly, as clockworks. There’s no development, no growth, barely any change to speak of. These are less songs than spaces, three-dimensional environments in which to wander for as long as Wendel deems necessary, and from the outside, the tracks’ lengths might as well be arbitrary. (What are the chances that he hit upon running times of 6:06, 7:07, and 9:09 by pure coincidence?) But while you’re immersed in it, the groove feels both infinite and unusually intricate.

Even in his scuzziest early years, Kassem Mosse’s music flickered like a candle flame, and the best tracks on workshop 32 are among the most propulsive in his catalog. The C- and D-side cuts are especially nimble, perpetually switching up the rhythm with ghost notes and stray bursts of keys or voice. There are echoes of Moodymann and Theo Parrish in his stubbornly soulful syncopations, and of Pépé Bradock in his gauzy weave of tones. Mostly though, he just sounds like Kassem Mosse, even if Kassem Mosse has never sounded quite like this before. In the closing “Provide Those Ends”—the only track to bear an actual title—a scrap of what sounds like film dialogue features a man muttering, “I’m trying, I’m working, I’m saving, I’m trying to do the best I can—provide those ends! I gotta work, you know what I mean?” Kassem Mosse is back on his grind, and he’s never sounded sharper.

0 comments:

Post a Comment