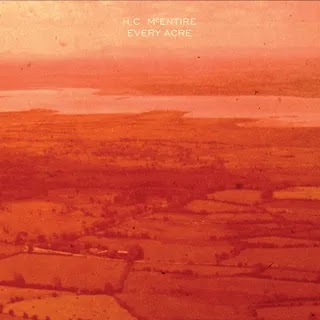

Tranquil and reverberant, the North Carolina folk songwriter’s new album finds relief and resolution in the circadian rhythms of the natural world.

H.C. McEntire has made a career complicating the music of her youth. A child of North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, McEntire began life on a family farm, her days soundtracked by the local country radio station. On Sundays, she’d attend church, the heavenward hymns lifting her out of her weekday twang. These influences have informed McEntire’s own reverent folk songs, whose gospel inflections and bucolic imagery reflect deep psychogeographic connections to the land where she grew up.

Sense of place remains the cornerstone of McEntire’s songwriting on Every Acre, an album that finds relief and resolution in the circadian rhythms of the natural world. Where 2018’s Lionheart and 2020’s Eno Axis imagined the land as a site of memory, from which McEntire tried to reconcile her queerness with her religious upbringing, Every Acre reconfigures the Southern setting as a scene of potential rejuvenation and regeneration: a place from which to begin the sluggish walk towards recovery. “It ain’t the easy kind of healing/When you’re down on your knees, clawing at the garden,” she sings in a viscid drone on “Rows of Clover.”

Slowness, and an appreciation for the long drag of time, is the album’s guiding aesthetic principle. McEntire’s world comes steadily and languidly into focus: The sound of croaking night frogs fills the hazy frame, while McEntire outlines a landscape of flowing rivers, stacked logs, ripe onions. She grounds herself in these details, attempting to lodge a restless and drifting mind into unerring, observable environmental fact. The songs’ tranquil pulse lends them a therapeutic quality that recalls the woozy and warm psychedelic tones of Neil Young’s Harvest Moon and the soniferous romance of Tammy Wynette’s We Sure Can Love Each Other.

It’s a peaceful contrast to the central preoccupation of McEntire’s lyrics, which concern self-effacement, sublimation, grief, and the singer’s ongoing struggle with depression. McEntire takes all of these subjects gently by the hand, befriending them. Her voice dances a dawdling waltz with itself: melismatic, drawling, half-drunk on sleep. Her guitar offers an even more languid counterpoint, as McEntire hammers off and on at the unhurried pace of a dipping bird. Slowness acts as a salve and a cure. Every Acre travels at the pace of healing, however long it takes a scab to suture a wound.

McEntire, a creative writing graduate, proved herself a deft and diligent lyricist on previous albums. Every Acre takes even greater advantage of the space where language fails and only music can fill the lapse. “Time ain’t always kind,” she repeats on “Turpentine,” delighting more in how the phrase sounds in song than how it reads as verse. On Every Acre, McEntire’s patient observations of the land provide her with a new footing: one full of possibility and promise. It’s in the commitment to stasis that McEntire finds the fortitude to begin anew.

%20Music%20Album%20Reviews.webp)

0 comments:

Post a Comment