The 71-year-old guitarist has long been known as a peerless interpreter of American musical forms, but on these 13 diaristic originals, he reveals more of himself than ever before.

Avant-garde jazz isn’t known for its gentleness, but Bill Frisell’s compositions are a fine-spun exception. Once a member of raucous early-’90s outfit Naked City, Frisell has spent decades at the crossroads of Americana and jazz, where he flirts with virtuosic, nostalgic pastiche yet never commits to any particular bit. The 71-year-old guitarist has delved into country, dabbled in surf, reworked classic movie scores, and even released an entire album of luxuriously orchestrated John Lennon covers. His fans admire the quiet sweep of his thoughtful arrangements and twangy, often vibrato-assisted tone, yet he’s accumulated his share of skeptics who paint him as a traditionalist. Many of his releases verge on beautiful formal exercises—they rarely touch on personal blues or divulge his beliefs about the country that spawned his source material.

Yet the Trump years and the pandemic marked a change. Frisell’s last couple of bandleader records revealed more of Bill, their conceptual underpinnings less prescriptive, more open to personal conviction—and as always, his collaborators were well suited to the task at hand. Americana, from 2020, was a panoramic joint effort with co-composers Grégoire Maret and Romain Collin, both immigrants who wove their complex outlooks on the titular genre into the record’s tapestry. Released later that year, Valentine expanded on its predecessor, drawing out the wounded innards of Burt Bacharch’s too-often trivialized “What the World Needs Now Is Love,” before Frisell bared his own politics on a treatment of “We Shall Overcome.” His latest, Four, harnesses a similar attitude: Having learned lessons from America’s musical history, Frisell spins them into a sense of doleful resilience in the face of the present.

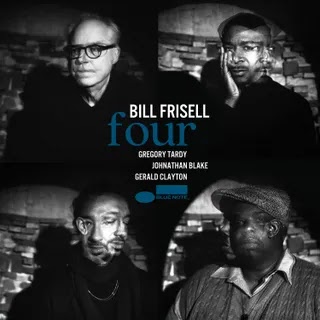

He sketched out nine of the record’s 13 tracks, all of which are originals, during quarantine. (A few of the other songs appeared in more subdued form on his 1999 masterstroke Good Dog, Happy Man, another on 1988’s pathfinding Lookout for Hope.) Accompanying Frisell is a brand new, nimble combo: Gerald Clayton on piano, Gregory Tardy on sax and clarinet, and Johnathan Blake on drums. Without a bassist, the group prances through airy melodies like acrobats on a wire. Yet sorrow always follows playfulness on Four, which dips and soars like the emotions of a single day. The result is one of the most structured, deliberate releases of Frisell’s career, a diaristic set that no one will ever mistake for a genre study.

The record is smattered with requiems for dead friends, dulcet pieces reliant on subtly shifting ostinatos. Opener “Dear Old Friend (For Alan Woodard)” starts with a duet between clarinet and piano that builds into the album’s stirring version of an overture. “Claude Utley,” about the Seattle artist, who died in 2021, transposes a piano refrain into a call-and-response—Tardy’s clarinet practically weeps, before Clayton and Frisell offer a two-chord riposte. Staggered melodies give “Waltz for Hal Willner,” about the famous producer and Frisell collaborator, who died of COVID in 2020, the swirling effect of sacred choral music. Yet the album’s middle mulls too long over moody straight-ahead and cool jazz, and on the dolorous “Wise Woman,” the band leans overmuch on repetition.

Still, such slow moments pay off. At the start of the LP’s fourth, final side, the musicians spring to attention with a lighthearted rendition of “Good Dog, Happy Man,” a callback to the record’s bright-eyed opening figure. Taken together, the two compositions act like beacons of hope illuminating Four’s rueful center. This sequencing strikes at the rhythms of real life, its surprising peaks and unavoidable valleys arriving in quick succession.

Over the course of Four, Frisell and co. build up a sense of forbearance, a painstakingly formed emotional callus. Bluesy closer “Dog on a Roof” numbers among his late-career finest. Starting with several minutes of guitar harmonics, ghostly piano, sax runs, and cymbal scraping, the players settle into a down-and-dirty groove more rugged and propulsive than anything that preceded it. Before the song ends, it dissipates into unnerving, whimpering free jazz, but the promise of that thrilling central section endures, spotlighting their long-sought middle road between grief and joy.

0 comments:

Post a Comment