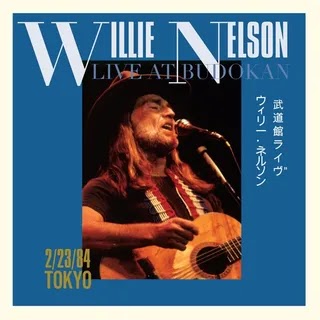

Recorded in 1984, this live set offers a glimpse behind the fog of pot smoke and blur of whiskey when one of country music’s greatest-ever bands was performing at its peak.

Frank Sinatra opened for Willie Nelson once. In Las Vegas. It was the early 1980s, around the time Ol’ Blue Eyes and the Red-Headed Stranger teamed up to cut a PSA for the Space Foundation. “We don’t share the same tailor,” a spotlessly groomed Sinatra quipped. “But we do share the same feeling about space technology, don’t we?” In truth, neither cared all that much about the cosmos, either; they were both massively popular performers in their own right, breathing the same rarified air, and they had simply been asked to combine their equal star power. It was an unlikely development. Willie had been a cult hero and a popular singer, but now, thanks in part to the hit ballad “Always on My Mind” and the worldwide success of his duet with Julio Iglesias, “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before,” he was a cultural sensation. It’s not at all surprising that, in keeping with one of the era’s greatest rock-star conventions, he cut a live album at Nippon Budokan in Tokyo in 1984. Nor is it surprising how supple Willie’s vocals are, or how impressionistic his guitar playing. What is surprising is how long it’s taken to see the light of day.

Live at Budokan was released in Japan on LaserDisc later that year and was subsequently bootlegged onto video cassette, but it remained largely obscure for decades, and is only now seeing wide release. It’s not the first live album to capture the depth of Willie’s powers as a singer and guitarist, his ability to command a crowd, or the underappreciated versatility of his Family Band; Willie and Family Live, from 1978, is every bit as essential as any of his pristine mid-’70s run. But the clarity of Live at Budokan’s production and the relative sobriety of the setting shows what was happening behind the fog of pot smoke and blur of whiskey when one of country music’s greatest-ever bands was performing at its peak.

Willie has always approached country music with a jazz sensibility. It’s easy to imagine Billie Holiday or Sarah Vaughan taking “Crazy” or “Night Life” for a spin, and his own vocal phrasing drifts around the beat, accents often dropping a single pregnant moment after you’d expect. On stage in Tokyo, the Family is in communication with one another in a way that owes plenty to both the feisty interplay of bebop and the stately arrangements of Western swing. Throughout the 90-minute set, Paul English’s drumming provides the bedrock for the rest of the band. Jody Payne and Grady Martin swirl up a galaxy of phased-out guitar in “Good Hearted Woman,” while Willie’s pianist sister Bobbie Nelson punches up the gospel filigree of her solo with a bit of heavy barroom playing. They draw unusual depths out of the classic song here, as if they’re freshly aware of the tension between cutting it loose and keeping it clean in the song’s lyrics; when they goose the tempo and change keys, it feels less like they’re moving through a well-established composition and more like they’re collectively choosing to let the good times drown out any protest.

They flutter into the delicate “Mona Lisa,” English’s pitter-patter dressing the Somewhere Over the Rainbow ballad like a millefeuille after the shit-kicking opener of “Whiskey River.” On nearly every song, Mickey Raphael plays harmonica in chortles, stomps, guffaws, anything but a melody, his short wads of rhythm matching the gummy phrases Willie tags on to most of the lines he sings with his guitar.

Willie’s approach to his instrument has been rhapsodized to the point of cliché; it’s likely that there are more people who have heard that Willie plays like Django Reinhardt than there are people who have actually heard Django Reinhardt. Perhaps owing to the effects of what Texas Monthly has noted could have been the first show he’d ever played without marijuana, his playing is crisp without being stilted, fluid without losing definition, and expressive in a way that can feel almost showy. Over a 20-second span in Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee,” he flashes a Tejana riff, doubles down into some heavy strumming, then glides back into the verse as smooth and pacey as a well-built car on a freeway.

In the mid-set “Loving Her Was Easier (Than Anything I’ll Ever Do Again),” another Kristofferson song, Willie picks up the motif from his “Whiskey River” solo, now treating it with a tenderness of touch that matches the lyric. It feels like a purer expression of the same romantic relationship he’d earlier begged the whiskey to wash away, which in turn makes the rowdiness of “Whiskey River” feel less like liberation and more like bittersweet heartache. Near the end of the night, he places “My Heroes Have Always Been Cowboys” next to “Mamas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to be Cowboys,” two songs that suggest cowboys are incapable of love, despite the fact that he’s spent the last hour or so demonstrating otherwise—or at least showing that a life on the range does offer one the chance to artfully share their introspection.

Willie’s ability to dress up complexity in the guise of old standards, campfire songs, Austrian waltzes, and hard-drinking anthems is just as crucial to his success as his ability to nail the high vibrato in “If You’ve Got the Money I’ve Got the Time.” In both the material he chooses and the way he presents it, he always comes off as a surprise; he’s the casual guy from around the way who turns out to be a hell of a musician. Like his pal Sinatra, he makes genius accessible, even quotidian. The Willie Nelson of Live at Budokan is an unlikely pop star—already over the age of 50, playing a distinctly regional style of music, with a voice that sounds like a drying saxophone reed—and it wouldn’t be long before he’d become an even more unlikely icon. But here, playing sad songs and waltzes with his Family Band on the other side of the world, he sounds relaxed and at ease, casual with himself and confident in his brilliance. Tokyo isn’t Texas, but in 1984, Willie kicked up stardust everywhere he went.

0 comments:

Post a Comment