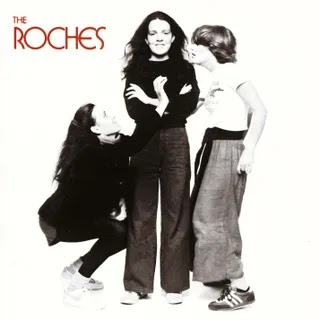

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the cult-classic 1979 debut from the Roche sisters, a playful, poignant, and slyly subversive folk masterpiece.

The Roches went down to Hammond, Louisiana, in 1975. Two of them: Maggie and Terre, who’d just released their first album, not yet joined by Suzzy, who would soon round out the trio. The elder two sisters had been performing for nearly a decade at that point, having first hit the road when both were fresh out of high school in Park Ridge, New Jersey, Maggie as a graduate and Terre as a senior-year dropout. Both had learned to play guitar from a public television program, quickly internalizing the dozen folk tunes the host had to offer. After that, rather than building up any standard repertoire or plugging away at fundamentals, they began focusing exclusively on developing Maggie’s original compositions, which flowed out quickly.

By the time Maggie and Terre met Paul Simon at an NYU songwriting workshop, they had an idiosyncratic sensibility as a duo, honed over years of small-time tours and local gigs at Greenwich Village folk clubs. Maggie’s songs mixed heartfelt sentiment and droll humor, plainspoken storytelling and poetic obfuscation, striking clarity of melody and knotty intricacy of form. Terre was ostensibly the lead vocalist, but in truth they were nearly always singing together, their voices entwined over their acoustic guitars. Simon, one of Maggie’s songwriting heroes, was impressed. He hired them to contribute backing vocals to his album There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, and got them a deal with Columbia, the same label that released his work.

Seductive Reasoning, released in 1975 and credited to Maggie & Terre Roche, didn’t receive much support from Columbia. The only feedback the label offered was that the sisters should wear hipper clothes. During the recording, as seasoned studio musicians played arrangements for Maggie’s songs from sheet music, “we realized that there was a whole thing that we had no idea about with music,” Terre put it to an interviewer later. They began to wonder whether their lack of musical education had left them unprepared for their fledgling new career. Two weeks after Seductive Reasoning came out, discouraged by meager sales and the label’s mishandling, Maggie and Terre resolved to quit performing entirely. They abandoned New York and its music industry for Hammond, a small college town of about 15,000 people.

“If you go down to Hammond,” all three Roches sing on their self-titled debut as a trio, released four years after that Southern sojourn, “You’ll never come back.” If you know “Hammond Song,” reading that line may be enough to conjure the miraculous sound of their harmonies in your mind. “Hammond Song” displaces the pressure Maggie and Terre felt not to leave New York, mapping it onto a family drama about a woman whose loved ones disapprove of her uprooting her life in pursuit of a man. Sometimes, the sisters inhabit different individual characters; at others, they come together in a shimmering Greek chorus.

Maggie’s lyric offers no answers about whether the woman is right or wrong to depart. The voices of her interlocutors radiate both loving concern and stifling control. You might sense, like them, that she’ll find only heartbreak in Hammond, or you might root for her leap into the unknown. The man, identified only with a dismissive “that fella,” is all but immaterial, just there to get the story moving. The heart of “Hammond Song” is the complex relationship between its protagonist and the women we can only assume are her sisters.

The arrangement illustrates those complexities as powerfully as the words do, with voices interweaving and dispersing, building chords that are first rich and sturdy, then fragile and uncertain. The writing is playful and poignant, often at the same time. “They say we meet again, on down the line,” offers Terre at one point, before a tower of voices upends the cliché: “Where is on down the line? How far away?” After the joke comes another blow to the heart. “Tell me I’m OK,” all three Roches sing together, their voices forming a delicate minor chord before spiraling downward.

While in Hammond, Maggie and Terre worked in restaurants and stayed at “a friend’s kung fu temple,” as their press coverage of the era uniformly put it, with understated puzzlement. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a bohemian martial arts institute in small-town Louisiana, it didn’t last forever. When the temple packed up six months later, the sisters did too, headed back to New York. Suzzy, their ebullient little sister, who had been 14 years old when they started performing, was now a college graduate living in the Village. She convinced her sisters to sing together again, and joined in herself, filling out the midrange between Maggie’s deep contralto and Terre’s crystalline soprano. They started by crafting elaborate vocal arrangements for Christmas carols and singing on the street. Soon, they were back in the folk clubs.

In their new trio formation, the Roches quickly caught on, eliciting a fervor that had previously eluded Maggie and Terre. Onstage, each took on a particular guise: Terre coolly charismatic; Suzzy the wild child, gyrating and pulling funny faces; Maggie the mysterious one, focused intently on the music. Maggie remained the primary songwriter, but the other two began composing as well. Along with their originals, they played a selection of covers ranging from Bob Dylan to George Frideric Handel. One newspaper reporter compared the flurry of positive press coverage to “the Bruce Springsteen hoopla in 1975.”

Mixed in with the rave notices was a sense of uncertainty of just what to do with these sisters singing painfully funny songs about workday commutes and affairs with married men in exquisite three-part harmony. Some writers insisted on reading deeply into their wardrobes—sneakers, thrift-store sweaters, peasant skirts, shorts and tights—construing these regular street clothes as evidence of coy affectation. Others sensed, in the Roches’ gleeful rejection of folk music’s po-faced past and utter indifference to prevailing trends, an affinity with the burgeoning rebellion of punk rock.

I Don’t Give a Fuck About This Rap Shit, Imma Just Drop Until I Don’t Feel Like It Anymore

One early champion was New York Times pop critic John Rockwell, who introduced the Roches to Robert Fripp when the King Crimson guitarist asked him about bands he should see in New York. Both Fripp and the Roches had recently signed contracts with Warner Brothers, the former as a producer and the latter as an artist. After catching a performance in the Village, Fripp approached the band about working together. Both parties agreed that the goal of the sessions, in contrast to the full-band arrangements of Seductive Reasoning, should be to replicate the Roches’ stripped-down stage performance as closely as possible, with few extra elements accompanying their voices and guitars. With the exception of some well-placed washes of electronics, and an iridescent electric guitar solo on “Hammond Song,” Fripp produced the Roches in much the same way that Andy Warhol produced the Velvet Underground: by letting them be.

This fidelity to the Roches’ live setup included starting the album with “We,” their customary set opener, a disconcertingly jaunty number that introduced the band in deadpan biographical detail: “Guess which two of us made a record/Guess what the other one did instead/The two who made the record/Have been a singing group for 10 years,” and so on. In a perceptive Rolling Stone review, Ariel Swartley described the gambit of “We” as “part confrontation, part playing the klutz.” And it’s true: “We” is a sort of gauntlet, an upfront announcement that the Roches will not be bending to accommodate received notions of artistic seriousness: male notions of such seriousness, if you want to put a fine point on it. It also serves as a dare to any listener who might dismiss them as a cutesy novelty act before “Hammond Song” shows up as the second track and obliterates that possibility. It doesn’t sound remotely like punk, but it’s a punk rock move through and through.

“Hammond” wasn’t the only song on The Roches informed by Maggie and Terre’s Louisiana limbo period. There’s also “Mr. Sellack,” one of Terre’s two writing contributions, sung from the perspective of a waitress begging an old boss to rehire her at a dead-end job she left for a failed attempt at stardom. Listening to its jazzy chord changes and piquant lead guitar, it’s hard to believe that the band was ever worried about their informal musical training. (The Roches, among other things, is a top-notch guitar album, with instrumental lines that at first seem secondary but sparkle and surprise with sustained focus.) If anything, it seems that the sisters’ boldness as teenagers—their impulse to plow straight into their own material rather than spend time figuring out how other people put songs together—yielded something original and rare. Each composition on The Roches is shaped unusually, each transition from one section to the next perfectly strange.

I Don’t Give a Fuck About This Rap Shit, Imma Just Drop Until I Don’t Feel Like It Anymore

One distinctive quality of their songs is the way a single line can shift the emotional polarity of everything in its orbit. In the case of “Mr. Sellack,” it’s the bridge, revealing the yearning beneath the greasy-spoon banality we’ve heard about so far: “Waiting tables ain’t that bad/Since I’ve seen you last/I’ve waited for some things that you would not believe/To come true.” The music bends and stretches around this admission: nudging toward a key change, picking up a couple of extra measures to accommodate all those syllables. The sisters’ phrasing and melodic lines are so graceful—shooting up to mimic the rising of the waitress’s dreams, then falling down dejected again—that the gesture sounds inevitable, almost easy, despite its irregularity. It’s as if the whole song were constructed outward from this one moment.

Lines like these abound in all three sisters’ songs, casting shadows across narratives that might otherwise seem purely whimsical. “The Troubles,” about a visit to Ireland, contrasts the sisters’ exaggeratedly petty concerns about the trip with the reality of a nation that was embroiled in brutal civil conflict. But you only hear about the second part once, and you might miss it if you’re not paying close attention. Suzzy’s “The Train” spends much of its time chronicling the unattractive excesses of an anonymous neighbor on the commuter rail: taking up two seats, drinking two beers, reading The New York Post. And then: “I want to ask him what’s his name/But I can’t because I’m so afraid.”

The Roches could be comically unsparing in their accounts of banality, another connection those early critics may have heard to the new wave of rock bands who yelped out their disenchantment with contemporary life. This was something other than folk music. There was nothing rustic about it. It was the folk music of kids who’d learned how to play guitar by watching TV. The band’s humor, and fondness for the quotidian, may have puzzled some listeners, but it was always in service of finding a deeper truth. “I think that’s kind of the nature of life, you know?” Terre told an interviewer earlier this year. “It’s not either/or it’s, and. Things are often heartbreaking and hysterically funny at the same time.”

“Damned Old Dog” is surely the saddest and sexiest song ever written with “bow wow” as a lyric. Maggie’s narrator wants to be a dog because it would make heartbreak simpler: Dogs don’t fall in love; they generally seem happy to mate with the nearest available candidate. The sisters enumerate this and various other advantages of canine life before realizing the transformation would be futile. “I don’t want to be a damned old dog,” they sing in descending harmony, sounding a bit like pre-Nashville country crooners. “I just want to lick your chin again.” At another point, their voices more closely resemble their subject’s: “Do I want to be a housebroken dog?” they ask, stretching the word “house” until it becomes the sound of three hounds howling at the moon. That’s not a metaphorical description: They literally start to sing like dogs. Somehow, it plays as much like tragedy as comedy.

I Don’t Give a Fuck About This Rap Shit, Imma Just Drop Until I Don’t Feel Like It Anymore

If the songs of The Roches have a unifying theme, it is the idea of leaving home. Again and again, the women at their centers take courageous and possibly ill-advised plunges, sometimes landing on their feet and others on their knees, begging to be taken back. Is the message of “Hammond Song” really so ambiguous? Of course she has to go down there. If it turns out to be a mistake, it will be one that she’s made for herself.

It’s easy to see the reflections of the sisters’ own paths through life. Despite the hype around their debut, the Roches were never a huge commercial success: The Roches, their biggest-selling album, peaked at No. 58 on the Billboard albums chart. “We have a career, and that is a gift. I guess I want things to be easy, but that’s not the way it is,” Maggie told The Los Angeles Times in 1995. But you never get the sense that they regretted hitting the road as teenagers, or getting up and trying again after the record industry failed them the first time.

Terre’s song “Runs in the Family,” a devastating ballad, suggests that boldness is part of the Roche temperament, and that it isn’t always easy to live with:

One by one we left home

We went so far out there

Everybody got scared

My uncle did it; my daddy did it

I'm beginning to think that it runs in the family

She keeps saying that—“I’m beginning to think that it runs in the family”—without ever quite saying what it is. It echoes my favorite lyric in “Hammond Song,” another one of those lines that jumps out and rearranges your feelings about everything in the story. The protagonist addresses her sisters: “I ain’t the only one who’s got this disease.” What disease? Later in “Runs in the Family,” a fight between partners leads, with a chilling lack of explanation, to a pregnancy. Who knows what sort of passion erupted in that negative space? The Roches, singing as one, seem sure that the child will be afflicted too: “Oh no, kid/You’re gonna run in the family.”

Maybe the disease is simply the urge to take a stand for yourself, and it’s only pathological because it risks being rejected, or worse, misunderstood. “Pretty and High,” the album’s elliptical closer, concerns a circus performer whose adoring public becomes convinced that she’s hiding something after she rebuffs a powerful man’s advances. They call her a liar, and claim that “if she takes off her dress/The sky will fall down.” It certainly sounds like a parable about the dangers of making art as a woman, for an audience that may turn on you as soon as you confound their expectations about womanhood.

“Call the eccentricity something else—more calculated than real, with an ingenuousness that is less than genuine,” wrote Alexander Austin and Steve Erickson in an L.A. Weekly review of a 1979 Roches performance. Women being so bold, so free, so funny—surely, they are trying to pull one over on us. They must be hiding something under their dresses.

0 comments:

Post a Comment