Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit Joni Mitchell's eighth album, an iridescent meditation on solitude, a masterpiece in her catalog and across all of music.

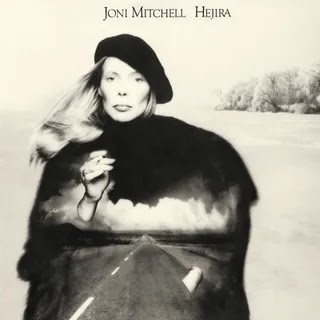

Joni Mitchell was running away. From what or where to have never been as vital in Mitchell’s songs as her in-betweens—between relationships and cities, between heartbreak and repair, between chords and tenses. From her early song “Urge for Going” through her travelogue classic Blue and beyond, Mitchell typified the woman wanderer, rarely represented in music. Hejira, her sprawling eighth album, embodies this quintessence. The road rolls out of her like a surrealist painting on the cover, combining bold realism and abstraction. Mitchell interprets the Arabic title meaning “departure” as “escape with honor.” She was returning to herself. “I suppose a lot of people could have written a lot of my other songs,” Mitchell once said, “but I feel the songs on Hejira could only have come from me.”

To begin with, however, in the spring of 1976, Mitchell was running from a doomed engagement, the chaos of touring, an increasingly inhospitable music business, cocaine, and home. It started, more or less, on Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue.

A clip from Martin Scorsese’s 2019 film chronicling that drug-and-nostalgia-soaked tour shows Mitchell outpacing her generation. It’s November, 1975, and she sits in Gordon Lightfoot’s house with her acoustic guitar and her black beret and a new song that would open Hejira a year later: “Coyote.” She wrote it on and about the tour—exposing sex-drugs-rock myths in lyrics about her peers’ “temporary lovers and their pills and powders to get them through this passion play”—but more accurately, she was composing “Coyote” in real time, improvising with her surroundings. To her right, backing her up and following her lead, was Dylan.

Mitchell’s longstanding admiration of Dylan led her to Rolling Thunder, and because she admired Dylan, she did not look back. She was busy being born. She had just released her misunderstood jazz-pop masterpiece The Hissing of Summer Lawns. It may be true that a younger Mitchell’s lyrics were liberated by Dylan’s 1965 single “Positively 4th Street.” It may be true that Dylan fell asleep in 1974 when she played him Court and Spark. But by 1975 the tables had turned. Dylan was revived in the wake of his Joni-inspired comeback, Blood on the Tracks. (“The most important thing is to write in your blood,” Mitchell had once said.) And during this acoustic performance at Lightfoot’s, with the Byrds’ Roger McGuinn on a third guitar, the look in Dylan’s eyes confirms what all knew, that at this moment Mitchell is the towering genius.

She had called herself a “singing playwright” since Blue, and she always narrated the dialogue, characters, and setting with her crescendoing soprano and the unconventional tunings of what she called her “chords of inquiry”—“They have a question mark in them”—as much as her lyrics. But “Coyote” adds new dimensions to the title. In a low speak-sing register, this fable presents “coyote” as the womanizing cowboy cornering Mitchell, “A prisoner of the white lines on the freeway,” and total mayhem. In one scene he’s “got a woman at home/He’s got another woman down the hall/He seems to want me anyway.” Two scenes later, “Coyote’s in the coffee shop/He’s staring a hole in his scrambled eggs/He picks up my scent on my fingers/While he’s watching the waitresses’ legs.” The titular “Coyote” is the playwright Sam Shepard, with whom Mitchell happened to have a brief affair. In her wittily wide-eyed first line, she captures the tour’s insanity while outsmarting this guy who she likens to a predatory animal: “No regrets coyote!”

At the end of the ’70s, Mitchell told Rolling Stone it was never her goal to be the queen of her generation, or the best. Her goal was to remain interested in music. Her steady gravitation toward jazz was proof, from Blue’s approximations of its textures to the experimental yet accessible Hissing of Summer Lawns. She considered the electric jazz fusion of Miles Davis’ In a Silent Way and Nefertiti to be the previous decade’s definitive records and absorbed their astral atmospheres. She was an avant-gardist among rock’n’roll people in an era when improvised music was creating rock stars of its own. Still, Mitchell inhabited that slippery space unique to those ahead of the times.

Rolling Thunder didn’t only fuel the luminous and literary “Coyote.” It also broke her down physically and left her addicted to cocaine. (She allegedly told the tour to pay her in coke and wrote ever-longer poems high late into the night: “Everybody took all of their vices to the nth degree and came out of it born again or into AA,” she said in 1988.) A month after, attempting to start her own tour for Hissing, her wrecked state and endless battles with her drummer John Guerin—the self-described “jazz snob” to whom she was engaged—resulted in its abrupt cancellation.

So the circus gave way to a spirit journey. Mitchell found herself sitting at Neil Young’s beach house wondering how to recuperate from such self-annihilation, longing to travel. Soon two acquaintances—one, an Australian former lover; the other, a lover-to-be—showed up together at her door in Los Angeles. The boys were going to drive cross country; their destination, for the Aussie ex with a 20-day visa and a grim custody battle, was Maine. “We were going to kidnap his daughter from the grandmother,” Mitchell said. “You could have made a whole movie about that trip.” (Paging Todd Haynes.)

Thirty-two years old with no license, Mitchell drove this band of outsiders east before looping back solo, down the coast of Florida and then along the Gulf of Mexico, “staying at old ’50s motels and eating at health food stores.” She adopted fake names like “Charlene Latimer.” She was often disguised in a red wig. She wrote most of Hejira on the guitar she kept in her white Mercedes. “I was getting away from romance, I was getting away from craziness,” Mitchell said, “and I was searching for something to make sense of everything.”

Hejira exalts the art of being a woman alone. It is restless music of road and sky, of interior and exterior weather suspended, epic and elemental. Her narratives unfurl with driving forward motion, telling stories of black crows and coyotes, of cafes and motel rooms; a bluesman and a pilot; psychics, hitchhikers, mothers, a guru. She contemplates eternity in a cemetery. She sees Michelangelo in the clouds. She hears jazz in the trees. Blue’s optimistic “traveling, traveling, traveling” gives way to an insatiable “travel fever,” each cartographic song extending the road further from Savannah to Staten Island to Canadian prairies, from Beale to Bleecker Streets. Her solitude distills the details into ascetic elegance.

The stark arrangements on Hejira, free of traditional structures, with only a few players on each song, are iridescent like glitter on icicles or sand. Mitchell stretches the unresolved tone of her “chords of inquiry” into a nine-song epiphany. The fretless bass, spare percussion, and unusual harmonics depict her wintry lucidity as well as the extremes of her existence, which she had accepted in service of her creativity. The protracted song lengths were allegedly a product of her drug addiction, while their clarity was inseparable from her process of getting clean.

She had started playing with the jazz fusionists of L.A. Express on Court and Spark—musicians who wouldn’t “put up a dark picket fence through my music,” as she once put it—and during a pit stop on her road trip, guitarist Robben Ford played her an advance copy of the debut album by Jaco Pastorius, an electric bass player who, like Mitchell, was really more of a painter. The 24-year-old had a tendency for introducing himself as “the greatest bass player in the world.” Mitchell (and most of the best bassists in his wake) wouldn’t have disagreed. She called the eccentric Floridian the bass player of her dreams. Pastorius used a knife to pry the frets off his instrument and transform it, playing more fluidly, flexibly, or as Mitchell called it, “figuratively” than anyone. Having only recently joined the intrepid Weather Report, Pastorius overdubbed parts atop four cracked-open Hejira songs, rhythms that liberated the music.

Hejira’s tenor is one of personal reconstitution, but Mitchell populates the lyrics with characters she met along the way, some literal, some symbolic, each representing a fundamental component of her character. “Furry Sings the Blues” describes her actual visit with the bluesman Furry Lewis near Memphis’ crumbling Beale Street, one birthplace of the blues, and could be an allegory for the corruption of a music business that left its pioneers behind, another parking lot paved over paradise. (That’s Neil Young on harmonica.) “A Strange Boy” recounts her disappointing tryst with her travel companion and his confounding immaturity, standing in for the overall inadequacy of men that Mitchell had contended with so often. It’s attuned to mystery, representing this guy she couldn’t crack in amazing dialogue, like, “He asked me to be patient/Well I failed/‘Grow up!’ I cried/And as the smoke was clearing, he said/‘Give me one good reason why.’” On the discordant “Black Crow,” Mitchell likens herself to the bird overhead, brooding, searching, diving. But the most powerful of these itinerant encounters occurs solely in her imagination.

On “Amelia,” she becomes the sky. Her ode to Amelia Earhart is soaring and celestial. “Like me,” Mitchell sings of the disappeared aviator, “she had a dream to fly.” This austere six-minute ballad takes the form of a conversation “from one solo pilot to another,” Mitchell has said, “reflecting on the cost of being a woman and having something you must do.” Ambition must often go it alone, and Mitchell accordingly subtracts bass and drums entirely. What sounds like sweeping pedal steel is really Larry Carlton’s electric lead guitar and vibraphone. The song’s harmonic character is an arresting question mark, both unsettled and at ease, just like solo travel, knowing there might be something, someone missing yet savoring the space created by absence. Mitchell spoke of Hejira’s “sweet loneliness,” to which “Amelia”’s major chords and resilience attest. “Amelia, it was just a false alarm,” goes Mitchell’s refrain ending each verse, ending every romance, too. As she sings of “driving across the burning desert,” likening six vapor trails to “the hexagram of the heavens [...] the strings of my guitar,” and how Earhart was “swallowed by the sky,” the whole forlorn song seems to go that way. Stars glint in its upper edges.

Clouds and flight, metaphors for freedom and what tempers it, had long been two of Mitchell’s central obsessions. She called descendants of the Canadian prairies, like herself, “sky-oriented people,” and writing on a plane in 1967, she had looked down on clouds to contemplate life, arriving at her standard, the timeless “Both Sides, Now.” But nine years on, in “Amelia,” she equates her living in “clouds at icy altitudes” with her long-standing depression that left her admitting she’s “never really loved.” When she pulls into “the Cactus Tree Motel” to sleep on the “strange pillows of my wanderlust,” the inn’s name is an allusion to her 1968 song about a woman “so busy being free.” Her life’s motifs knock the door in Georgia, too, on the winking torch song “Blue Motel Room,” where rain turns the ground to “cellophane,” a word Mitchell famously used to describe her defenseless Blue era; “Will you still love me?” she yearns coolly, echoing a formative influence.

Of all the land Mitchell traveled, though, the space and otherworldly plantlife of the arid Sonoran Desert seem to have made the greatest impact, as evidenced on “Amelia.” The desert is an isolated landscape pitched to infinity, a place to confront yourself and your insignificance in the scheme of things. On her song named for a desert creature, “Coyote,” she voices her desire “to run away” and “wrestle with my ego.”

Her ego-erasing quest comes to a head on “Hejira.” The title track is a sprawling monument to her decade of turning personal catastrophe into philosophy, laying bare her cardinal themes. “Possessive coupling.” “The breadth of extremities.” “Comfort in melancholy.” Unlike Hejira’s other songs, it contains few proper nouns: it specifically confronts the existential expanses of muted despair instead, illumination eclipsed with pain in the music's depths. She’s “traveling in some vehicle.” She’s “sitting in some cafe.” She’s “a defector from the petty wars that shell shock love away.” If heartbreak redeems itself by creating knowledge, then “Hejira” locates the precise coordinates where that shift occurs. Nowhere in her catalog does she create a richer or more rigorous self-portrait.

I know no one’s going to show me everything

We all come and go unknown

Each so deep and superficial

Between the forceps and the stone

On “Hejira,” Mitchell interrogates her 32 years. She had made profound sacrifices for the sake of her art, which perhaps accounts for the music’s intensity: When you feel you’ve sacrificed everything for your work, you bring everything to it. She looked for answers in every corner of the country her car could reach. She poured in every reserve and inexhaustible query. What are the uses of solitude? How close to nerves and bone can you get? Is art worth the sacrifice? Could she ever fully be seen? Her music stretches into a dissolving horizon suggesting the questions are unanswerable. Its unresolved charge suggests that life will be a cycle of finding meaning in the questions. In the spartan space, Mitchell invites us to complete the picture.

Staring at headstones on “Hejira,” “those tributes to finality,” pondering death, she considered her life. “I looked at myself here,” she sings, “Chicken scratching for my immortality.” Even Joni Mitchell must sometimes feel meaningless, at the top of the mountain, wondering what everything is worth. She always said she embraced granular details in her autobiographical art songs because it made a better story, and people should “know who they’re worshiping.” Here she offers a metaphysical magnification of her most atomic truths.

We’re only particles of change

Orbiting around the sun

But how can I have that point of view

When I’m always bound and tied to someone

Two other of Hejira’s songs illustrate as much. “Song for Sharon” is Mitchell’s reckoning with her position as single and childfree in her 30s, subverting the status quo in subject and in form. She’d addressed this reality before, like on For the Roses’ “Woman of Heart and Mind.” But in this nine-minute letter to her long-lost friend back home, Sharon Bell—who took a conventional path, “a husband and a farm”—she went further, surveying the advice she’d received from other women about how to give her life meaning: “have children,” “find yourself a charity.” With unbothered resolve and an even-handed tone—not innate for Mitchell—she situates herself between these two pathways of womanhood, seeking the common ground between herself and Sharon, or maybe between herself and all women, like her mother and grandmother who suppressed their dreams. “Song for Sharon” blows up the myth of the pop renegade with no direction home. Staring the past in the eye, Mitchell admits (in a call back to Blue’s “All I Want”), “All I really want to do right now is find another lover,” the last word drifting like smoke.

The most significant of its 10 verses was inspired by the actress Phyllis Major, who died by suicide in March of 1976. “A woman I knew just drowned herself,” Mitchell sings about the wife of Jackson Browne, who she herself had also dated, and whom she despised. (Her 1994 song about domestic violence, “Not to Blame,” was written in the wake of accusations against Browne, too.) “It seems we all live so close to that line,” Mitchell sings, “And so far from satisfaction.” “Song for Sharon” becomes a multifaceted song of solidarity with a diversity of women seeking dignity and respect. Its length illustrates the endlessness of such a task.

Hejira built a new sound to match the feminist paradigm it presented for being a woman in the world, with autonomy, adventure, and pleasure all as virtues. In the mid-’70s, the trope of the solo male traveler seeking enlightenment in meandering solitude was well-defined by tales like Walden and On the Road, even Siddhartha. Women travelers were unknown. Mitchell’s position “made most people nervous,” she sings on the beautiful, gently loping album closer, “Refuge of the Roads,” which describes her meeting with Tibetan Buddhist spiritual teacher Chögyam Trungpa. But her role brought others to life. In 1959, Simone de Beauvoir had posited, in The Second Sex, that “the free woman is just being born,” and when she arrived so would her poetry. Hejira is evidence, a shapeshifting aesthetic to voice a still-emerging mode of being female.

“Here’s the thing,” Mitchell told Rolling Stone in 1979. “You can stay the same and protect the formula that gave you your initial success. They’re going to crucify you for staying the same. If you change, they’re going to crucify you for changing. But staying the same is boring. And change is interesting. So of the two options, I’d rather be crucified for changing.”

Time had another idea. For years, the prevailing Mitchell narrative positioned Blue as her creative peak, Court and Spark as her commercial apex, and everything else a fascinating slow fall. This is, of course, incorrect. Creatively, if not commercially, Mitchell’s entry to jazz—the second half of what biographer Michelle Mercer calls “her Blue period” from 1971 to 1976—was more akin to Dylan going electric and cresting on an upward stride. She had adapted a new language for her trio of albums leading to Hejira like Dylan’s triptych leading to Blonde on Blonde.

Hejira’s influence remains as boundless as the music. Along with inspiring the Rolling Stones, Hejira is among the Mitchell albums that a young Björk held in the highest esteem. In recent years, Danielle Haim, Weyes Blood, and St. Vincent have anointed it as their favorite. In 2019, pop experimentalist Jenny Hval wrote a song about the act of listening to “Amelia.” Hejira created a precedent for the pantheon of art about women alone in motion that now includes Agnès Varda’s Vagabond and Patti Smith’s M Train.

The month of Hejira’s release, in November of 1976, Mitchell played “Coyote” as part of the Band’s Last Waltz. She herself didn’t tour for three years after, living “in exile from a mainstream audience,” as Rolling Stone put it when she resurfaced with her Charles Mingus collaboration in 1979. She either understood her staggering achievement or lost what little remained (had it existed) of her faith in the “star-maker machinery” of highly commercial music. She knew “no one’s going to show me everything,” as she sings on the title track, so she fulfilled her dreams herself. She wished for a river to skate away on. Hejira became one.

Additional research by Deirdre McCabe Nolan

0 comments:

Post a Comment