In the 1970s, the Downtown saxophonist fused free jazz’s fire-breathing spirit with minimalism’s dizzying swirl. Three new reissues from Unseen Worlds document the evolution of his unique style.

To hear Dickie Landry tell it, he’s been in the right place at the right time for decades. Within weeks of moving to New York City in 1969, he had met Ornette Coleman, Philip Glass, and Steve Reich, forging lasting relationships with each. He was working as a plumber alongside Glass when he started photographing icons of the Downtown art scene, documenting the embryonic careers of sculptor Richard Serra and multimedia polymaths Keith Sonnier and Joan Jonas, as well as Glass’ ensemble, which he had just joined on saxophone. He bonded with Paul Simon and ended up playing sax on Graceland after introducing himself at a Carnegie Hall performance; he sat in with Bob Dylan at 2003’s New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, the day after a chance meeting through a restaurateur friend. Despite his relative obscurity, Landry has been ubiquitous, repeatedly finding his niche among artists looking to push their work beyond the familiar.

Landry’s music occupies a peculiar, non-idiomatic zone all its own. He grew up on a farm outside Lafayette, Louisiana, in the 1950s and ’60s, playing saxophone from the age of 10 and diving headfirst into the jazz and zydeco that surrounded him. Early on, the multi-reedist saw the strange and thrilling results of cross-cultural exchange, and he carried that spirit with him to New York, where he shepherded many other Louisianans into the thriving avant-garde art and music communities of Lower Manhattan. Throughout the early-to-mid ’70s, as he became a key member of the Philip Glass Ensemble, Landry staked out his own corner at the intersection of free jazz and minimalism, developing a unique style of improvisation that unites the former’s fire-breathing revolutionary spirit and the latter’s dizzying swirl.

A new trio of reissues from Unseen Worlds—Solos, Four Cuts Placed in “A First Quarter”, and Having Been Built on Sand—documents the evolution of his style. Each album sprang from Landry’s connections across the avant-garde, but even when the music was recorded in a gallery setting, nothing about it is tidy or inert. Like fellow Glass Ensemble member Joan La Barbara, Landry harnesses the technicality and endurance that Glass’ music requires and puts it to work in far more esoteric—at times anarchic—contexts. As the ’70s progressed, Landry’s music became increasingly fixated on tonality and rhythm, but these three albums present a musician determined to confront and confound, even when he embraces repetition and melody. The music runs from rapturous, long-form group improv to hushed, circular melodies overlaid with cut-up poetry, but the most revelatory bits lie squarely in the middle.

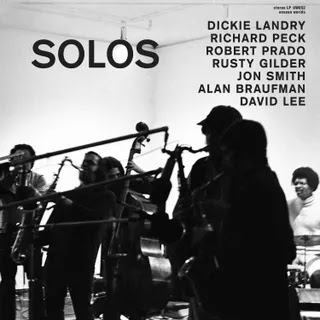

From its very first seconds, Solos squirms in a million directions at once. Cut from a single, continuous session at the Leo Castelli Gallery over one night in February 1972, the album is a tangled thicket of bluster and skronk. Joining Landry on soprano sax and electric piano were seven other improvisers, including three additional saxophonists, two bass players, and drummer David Lee Jr., who emerges as its heroic figure and provides relentless forward motion throughout the album’s nearly two-hour runtime. Cohesion seems coincidental throughout, and while each player ostensibly takes solos in turn, collision and overlap are the rule rather than the exception. It’s as close as Landry got to paying homage to Ornette Coleman (whose “Lonely Woman” he quotes about halfway through), John Coltrane, the AACM, and the era’s other giants of improvisation. Here he is at his most unrestrained, reveling in the power of collective instantaneous invention. Yet Solos—immersive and at times overwhelming—lacks his next album’s clarity of vision.

Recorded just nine months later and with four of the same players, Four Cuts Placed in “A First Quarter” takes an introspective turn. Of its four distinct pieces, only the opening “Requiem for Some” features the full ensemble, with Landry focusing instead on solo and duo formations—a format that would define his work for the rest of the decade. “Requiem” showcases restraint, the horns exhaling long, sustained tones while Lee traces out ever-shifting patterns around his kit. For the rest of the album, including in its most brash moments, the empty space around the players is palpable, and Landry and his associates seem to be in constant dialogue with that absence. These minimalist settings are partially a result of practicality—the music accompanied a similarly oblique experimental film by Lawrence Weiner—but divorced from that context, even the most rudimentary musical gestures feel vivid.

“4th Register,” the second and most mesmerizing of the Four Cuts, documents an important step in Landry’s musical progression. Here he stands alone with his horn, working out increasingly abstracted variations on a folk-like refrain until it boils over into microtonal squeals. Each sound that his sax produces is fed into a half-second tape delay, a technique he would expand in live performances over the years leading up to his landmark 1977 album Fifteen Saxophones. “Vivace Duo” features Landry and fellow saxophonist Richard Peck in a 10-minute duel to see who can blow hardest and fastest, and the chaos is accentuated by the stark atmosphere. Each of the Four Cuts is emotive and direct, made all the more powerful by its simplicity.

The simplicity remains on Having Been Built on Sand, another collaboration with Weiner, but there’s a sense of detachment throughout that dulls its impact. Each track features Landry ruminating on a short melodic fragment while Weiner, Britta Le Va, and Tina Girouard recite the title phrase, lyrics of German folk songs, and other short pieces of text, seemingly without much conviction. Despite some inventive embellishment by Landry, and the remarkable resonance of the recording space (which belonged to Robert Rauchenberg), the album’s purposeful obscurity is a letdown, especially after listening to the passionate, laser-focused recordings that preceded it. Landry’s most potent work starts deep in the gut and then reaches for the outer limits of what music can do. That fusion of uninhibited grit and creative expansion illuminates his singular artistic spirit, restlessly in search of transcendence.

0 comments:

Post a Comment