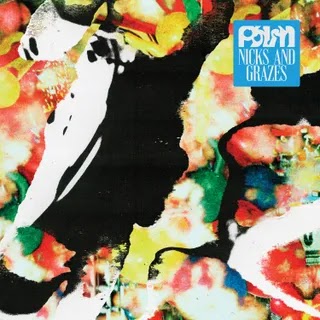

On its third album, the Philadelphia quartet hones the studio techniques—as well as the knowledge of when to hold back—required to do justice to the group’s adventurous spirit.

What is psychedelic music? The question has followed Palm since their beginnings in the college-town basements of Upstate New York, and has been thoroughly documented on albums like 2015’s Trading Basics and 2018’s Rock Island. With little formal knowledge of how to play their instruments when they first formed, the quartet—now based in Philadelphia, and made up of Eve Alpert, Kasra Kurt, Gerasimos Livitsanos, and Hugo Stanley—has followed the art-school impulse to question assumptions about how rock music is structured, building an alien system of its own. Showing a reluctance to be boxed into any single genre, the group has retained an openness to the possibilities of sound at its most elemental, using music technologies in strange and unorthodox ways that feel broadly in tune with the psychedelic moment of the 1960s. Palm tap into a cosmic excess bound up in the elaborate vocal effects and electronically treated guitars that are slathered across their albums, reclaiming psychedelic music as more than just a dorm-room backdrop for getting stoned. Their third studio album, Nicks and Grazes is dizzying and complex without losing sight of the progressive rigor that has guided the band since its beginnings.

To listen to Palm is to observe patterns in a foreign language, waiting for a logic to emerge. On Trading Basics, they seemed to consciously embrace a history of experimental tropes, grounding their music in a noise-rock lineage. Yet with each release, they’ve taken steps to replace this scaffolding with a new foundation of their own, with varying degrees of success. Recorded just two days after the release of Trading Basics, 2017’s Shadow Expert EP incorporated new studio techniques that built on the tight-knit feeling of the group, ping-ponging across stereophonic space as if to mimic dialogue and dialing in effect pedals with more precision than their earlier lo-fi efforts. But the endless changes and sustained hyperactivity made for a difficult listen, a feeling that would continue on their 2018 album Rock Island. Roughly four years later, Palm have finally developed the studio techniques and conscious sense of restraint needed to do justice to this adventurous spirit, creating an album that’s precise and exacting as it approaches new terrain.

Their organizing principles are as unconventional as ever. Babbling synths and wind chimes give way to controlled chaos on “Touch and Go,” as corkscrew guitars offset Stanley’s propulsive drumming. While they’ve long been invested in outlandish recording techniques, Palm now seem set on building out a studio sound that contributes to the forward motion of the project. In most cases, this means the addition of new electronic elements, like the metallic samples and synth pads deployed throughout “Touch and Go,” or the thumping synth bass on “Feathers.” The latter track is built entirely around the instrument, smoothed over with a soft counter-melody from Alpert before erupting with electrifying drums. Yet even as they approach something ostensibly similar to dance music, they can’t help but sound like a more realized version of themselves.

For many bands, the idea of a polished studio album has become synonymous with the big-budget techniques of the 1960s and ’70s, but Palm are rarely, if ever, nostalgic. Noise and art rock were always points of departure for defining a sound of their own, and while their use of steel-drum samples has long felt like a nod to the global diasporic genres they’re inspired by, the band has never set out to make the next great calypso record. The best comparison might be to the studio recordings of Yellow Magic Orchestra and their lasting influence on Japanese synth pop, but even then, the band is much more interested in melody than acts like Sympathy Nervous or R.N.A.-ORGANISM ever were. Decisions about arrangement and studio techniques emerge naturally from the band’s increasingly focused interest in sound design, establishing the central axis around which the album revolves.

Firmly uninterested in recreating the sounds of any historical era, Palm instead construct their own alternative to the studio-as-instrument philosophy of this midcentury period. Songs like “Away Kit” and “Tumbleboy”—a track which first appeared on Kurt’s split release with Ada Babar from 2017—feel like logical next steps for a group already so committed to rethinking how the band and the instrument should function. Roughly halfway through the ambient interlude “And Chairs,” a small voice asks listeners to follow them in guided meditation. “Just listen to what you can hear, you and your surroundings,” they say. Like this interlude, Nicks and Grazes asks us to reconsider foundational ideas about what music is, how it works, and what we expect of it at every step of the production process. It’s a totalizing vision for the band as an artistic unit, one that organically builds on everything they’ve done so far.

0 comments:

Post a Comment