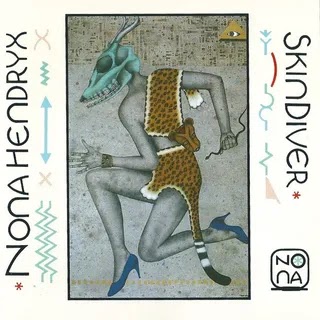

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit a buried treasure, the 1989 experimental new age solo album from the R&B legend, a Black queer epic where technology mediates tenderness.

Sheathed in reverb, forged in the heat of an artist combusting her prodigious talent, Nona Hendryx proclaims: “Women who dream don’t stay too long.” It’s a faceted message, sung by a bisexual Black woman in her mid-40s who’d already been in the game for some 25 years. By the time “Women Who Fly,” the first and only single from her 1989 album SkinDiver arrived, Hendryx had an unrivaled list of accomplishments as an innovator of ’60s girl groups, a crucial member of ’70s Afrofuturistic soul force Labelle, and a firebrand of ’80s funk-rock. But she was shamefully under-heralded, and women, especially Black women, who didn’t make hits didn’t stay too long in the music business.

Someone else might have called it a day, or become a nostalgia act. Instead, she took up with an ex-Tangerine Dream synth whiz and made an album that amalgamates new age and adult-contemporary strategies into a song cycle of machines and mindfulness. At the end of the 1980s, Hendryx heard the sound of a new world, one in which technology mediates tenderness. Modern electronics and ancient drums and the timeless demand to love directly, and to be loved in return, have their place here. SkinDiver is a Black queer epic on a human scale.

Hendryx was born in New Jersey in 1944. “I came from a ghetto, a real one—Trenton. I lived hard and I can’t forget it,” she later told Essence. “Yes I wrote poetry even then, but I was on the street.” She was also in the church. A young Hendryx was singing in a choir when a member of a visiting choir, Sarah Dash, first heard her roar. As detailed in Adele Bertei’s laudatory Why Labelle Matters, Dash asked Hendryx to join her a cappella group, the Del Capris; in 1961, that group’s manager signed another group, the Ordettes, featuring a young but already mighty Patsy Holte. In the long tradition of managers mixing and matching Black voices and faces, the manager would soon recast the groups into the trio of Dash, Hendryx, and Holt, along with a fourth member, Cindy Birdsong. Now known as the Bluebelles, the group were the face of, but not the singers on, a hit song called “I Sold My Heart to the Junkman.” The original singers found out, the Bluebelles re-recorded the track, Patsy Holt was rechristened Patti LaBelle, Hendryx dropped out of high school, and the act hit the Chitlin’ Circuit, the Black DIY network of venues that, under Jim Crow, were as safe as spaces could get.

Such shape-shifting would be a constant for Hendryx. While superstardom eluded Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles, they put out some exemplary records and toured with the Rolling Stones. By the end of the decade, though, Birdsong defected to become one of the Supremes, whose style felt a bit recherché to the trio. In London, the three women met Vicki Wickham, producer of the influential BBC rock show Ready Steady Go!, who became their manager and hipped them to the city’s gay underground. They refashioned a fascination with Sun Ra and the right-on funk-rock of Sly and the Family Stone into a new life as Labelle and opened for the Who and Laura Nyro, with whom they made a revelatory record of sexuality and solidarity, 1971’s Gonna Take a Miracle. They made a quintet of out-of-this-world albums, and Hendryx wrote a lot of the songs on them, starting with their political and percolating 1973 album Pressure Cookin’. Onstage, decked out in space-age silver lamé and feathers, they were a riot: Parliament-Funkadelic may have lifted a spaceship into orbit at their shows, but Hendryx descended on wires to stalk audiences with a whip.

The gay singer-songwriter Bob Crewe, with writing partner Kenny Nolan, would pen their biggest hit, 1974’s sex worker paean “Lady Marmalade,” but Labelle surely are equally responsible for bringing it to life. Its strident and bilingual bawdiness, not to mention their record label’s perplexing inability to promote follow-up singles into the hits they should have been, led to irreparable fractures within the group. By 1976, Labelle fizzled. Their too-muchness had at last become too much. Sarah Dash recorded some ferocious hi-NRG records with Patrick Cowley and Sylvester. Patti became, of course, Ms. Patti LaBelle. Wickham managed Dusty Springfield, Marc Almond, and Morrissey and remains Hendryx’s long-time partner in work and love. Labelle reunited a few times. Dash died suddenly in 2021.

Hendryx went her own way. In 1977, she released a glammy self-titled debut that didn’t take flight. She joined Talking Heads, lending her voice and, let’s just say it, authority to their Remain in Light album and tour. (“The Great Curve” without her? Flatline.) As the ’80s arrived, she worked with everyone: Bill Laswell’s Material, on the disco-not-disco classic “Bustin’ Out”; Nile Rodgers, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, the Compass Point Studio geniuses. Prince wrote a song for her. Four albums came and went, including 1985’s hard rocking The Heat and 1987’s guitar-heavy/proto-new jack swing Female Trouble. “People still have this difficulty categorizing me,” she told NME. Black women had played rock’n’roll since its birth by Big Mama Thornton in 1952, but Nona’s seat at the table was suspect to the white music establishment. In the Village Voice, Robert Christgau first objected to her “insatiable desire to make rock records”; a year later, his take was that “she just isn’t as talented as you wish she was.” In 1987, the Los Angeles Times went further, grossly dehumanizing her as “a pedigreed workhorse, bred and groomed to fill conglomerate coffers.” Her labels kept dropping her. “I don’t want anyone to be like me,” she told NME, “but I want them to see the possibilities.” What was left to show?

An answer came in Female Trouble’s Peter Gabriel duet “Winds of Change (Mandela to Mandela).” The earnest tribute to the South African anti-apartheid revolutionary culminated in an ascension to a sparkling paradise of clear, tolling bells. It echoed the kind of twinkling arpeggios Tangerine Dream coaxed out of their machines—and, indeed, its founder Peter Baumann did the song’s sound production. Baumann had launched his label Private Music in the early ’80s to release landmark experimental-ambient albums by Suzanne Cianni, and also Yanni. The indie label would become a sympathetic venue for the hypnotic grooves she’d been programming on the computer in her New York City apartment. In the announcement of her new album, 1989’s SkinDiver, she called her home “a cubicle in a mass of metal,” and its songs sounded like that, soft private spaces to work in a hard world.

Like all of us, Hendryx longs to connect. SkinDiver maps out the ways. There is sex, and intimacy, its sometime companion. “Off the Coast of Love” swells in with electronic patterns of flutes and drums that paddle and struggle like feet against the tide. “Love would wash me ashore!” she bellows, as tom-toms thunderclap and lightning-bright orchestral stabs flash around her. But she remains unquenched. On the title track, a mid-tempo heater that throws off rumpled harmonies and folds of rhythm like sheets from a well-made bed, Hendryx details her failings. She’s negging herself in the service of seduction, or confessing just what a lover might get into with her. She needs more control, to be less controlling. She lays out a come-on: “I’d like to feel how you feel…I imagine it’s a thrill…I’m a skin-diver/So into you.” It’s a trip under the covers and into someone else, an escape through penetration.

For a moment, anyway. Much of SkinDiver happens in the moments where being in your body feels unbearable. “Women Who Fly” soars with rueful glory. There’s a bit of the Blue Nile’s synth-pop and a bit of Annie Lennox’s mask-that-tells-the-truth in the way Hendryx promises that “I’m most dangerous when the skin that I’m in isn’t mine.” But as a Black woman in her 40s, a queer person in the AIDS crisis, a legacy artist whose past hasn’t earned back—for Hendryx, the stakes are much higher. She’s about to blow. On “No Emotion,” she and Carole Pope, of the hugely-underrated Torontonian queer rock band Rough Trade, chant, “No emotion we must show,” while guitars worthy of Kevin Shields squall and cymbals worthy of Budgie throw tantrums. It’s an ironic catharsis that burns itself out, too hot to handle.

Hendryx can do the regal machismo of Grace Jones with abandon, but elsewhere the ice queen is melting. “Love Is Kind” is all thaw, her keys dripping over caresses of fretless bass. In a voice shadowed with echoes that extend in strange directions, she promises to take care of herself, even if that means humbling herself before a world that doesn’t deserve it. She’ll stop overthinking. She will feel love. And yet, like the endless arpeggios on a keyboard, the old patterns continue. In “Tears,” a heartbeat of a drum machine cradles blankets of organs. “My heart,” she says. “My head.” It’s Descartes as dream pop. Because it’s 1989, dolphins chirp. (They might be whales. Or Drexcyians.) “Who am I?” she cries out. The words reverb into nothingness.

SkinDiver can hypnotize on its way to oblivion. But Hendryx will not let alienation win. To really be embodied, one must acknowledge the terms of this world. Sampling both Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy, threading images of mediated violence like an uncynical version of Cabaret Voltaire into a showstopping belter from a cynical Céline Dion, “Through the Wire” is a blistering power ballad about power. Yet this is not the only power. In the audacious “Interior Voices,” structured like a clapping game, and also like future Vespertine-era Björk, Hendryx finds other sources. “The past and the present live as twins,” she sings simply. “God and the devil, fear and dreams/Pass from mother to child, an unbroken stream.” The Great Communicator is the umbilical cord; the coming World Wide Web is an amniotic sack. Drumrolls rustle like feathers. A children’s choir coos. It’s stunning, a bit camp like Kraftwerk were, a dazzling and generative kind of Woman Machine.

The album’s peak refuses all the old power structures. “6th Sense” reincarnates her old friend Patti LaBelle’s “New Attitude” into a new age anthem. Deep in thickets of wood blocks and pan flutes, Hendryx muses on superstition. She chants down those who’d deny her intuition. Unlike Patti, she hasn’t tidied up her point of view: “I believe in déjà vu, ancient dreams, and primal screams that run beneath the conscious stream,” she declares. But isolation threatens enlightenment. “Is anyone listening?” she hollers, again and again. “Can anybody feel me? Does…anybody…care?” There is more to this world, and more to herself, than one might believe.

SkinDiver comes to rest in the afterglow. For “New Desire,” fingers tickle out a melody, and bells linger like embraces. She’s plummeting back to earth, and a bass glides to find the landing spot. There’s a subtle ticking noise in the distance. Hendryx has been on the trip of a lifetime, all alienation and love sensation, finding and losing her place in the world and making of it what she will. Her voice gathers force for one last lesson. “Love is the door through doubt and distance,” she says. And she’s right. “I surrender,” she says. But not to what you think. SkinDiver begins with Hendryx needing to hold someone; it ends with a call to arms around her. She’s yielding not to desire but to being desired. She’s learning to be loved in a world that mostly won’t. “Touch me,” she sings. “I’m waiting.”

Hendryx waited for people to catch up to SkinDiver. “I’d like it to be discovered rather than sold to people like the latest fashion,” she told Billboard in 1989. In 2007, she turned SkinDiver into a sci-fi multimedia rock musical at NYC’s downtown demimonde HQ Joe’s Pub. In the 2010s, she made a few fab house collaborations with Soul Clap, and in 2017 released a revelatory collection of Captain Beefheart covers with Gary Lucas. For the bridge of “Women Who Fly,” Hendryx warns all who can hear her: “Don’t give me wings and take away my sky!” It’s hard to imagine someone strong enough to clip her ambition. Her work keeps expanding. Almost 35 years later, SkinDiver remains a vista to gaze in wonder at, and wonder what else is on the horizon.

0 comments:

Post a Comment