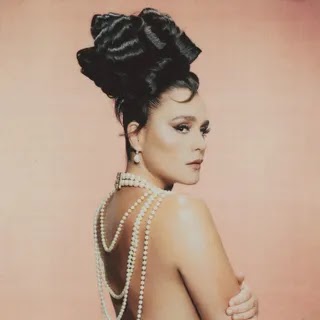

With her 10th album, Björk is grounded back on earth, searching for hope in death, mushrooms, and matriarchy, and finding it in bass clarinet and gabber beats.

Hope springs eternal in Björk’s fantastical world. Her optimism is one of the most spiritually nourishing things about her work, as if she’s dressing the emotional wounds of the world despite making increasingly avant-garde music and becoming the world’s first Animorph. At times her lyrics have urged the listener to accept a lack of control as an opportunity—the way there are “unthinkable surprises about to happen” on Vespertine’s “It’s Not Up to You,” or how Post imagines romantic hope through self-possession. You can always find the spark or glimmer of light in Björk’s music, whether it’s in the outlook or the instrumentation.

Of course, her emotionally complex canon, spanning nearly 30 years, also shows that unthinkable surprises can be catastrophic, most acutely on 2015’s Vulnicura, written about her painful divorce from the artist Matthew Barney. Without the lows, there would be no hero’s journey for Björk, no abyss, no transformation, no return. She embraced new love on 2017’s Utopia, a fantasia of flute and birdsong, and she has been embraced herself, as a blueprint of autonomy for women artists and as some kind of experimental-pop “mom” for young fans. With her 10th album, Fossora, she is grounded back on earth, searching for hope in death, mushrooms, and matriarchy, and finding it in bass clarinet and gabber beats.

The most poignant songs on Fossora are the towering twin tributes to her mother, the environmental activist Hildur Rúna Hauksdóttir, who died in 2018. The first, “Sorrowful Soil,” is Björk’s attempt to mimic Iceland’s traditional style of musical eulogy, consisting of melodramatic melodies delivering dry biography, but from a matriarchal POV. “In a woman’s lifetime she gets 400 eggs but only two or three nests,” she sings, pausing for emphasis and buoyed by women’s voices from the Hamrahlid Choir. With a baroque choral arrangement and bass chords that function like a church organ, the song sounds solemn, to be sure, but there’s something strangely funny about boiling down a woman’s life to her menstrual cycles and prevailing worldview (Björk seems to recognize this, grinning over the lyrics’ oddness in our recent cover story). Certain phrases cut through and carry the melody: “emotional textile” (what a mother’s nest is made from, naturally), “self-sacrificial,” and “nihilism.” Björk’s mother was a nihilist, a fact that is dramatically emphasized in a vocal hook; despite her nature, the musician seems to say, she did her best to raise children, an act that disregards one’s own nihilism for the future.

“Sorrowful Soil” was written before Björk’s mother passed, and “Ancestress” was written after, as a more personal eulogy. Built from anthemic strings, sparse beats, a sprinkling of chimes and gongs, and vocals from Björk and her son Sindri, “Ancestress” is among the singer’s most striking songs about hope because it shows the limits of it. The lyrics reflect the arc of a mother and daughter’s love passed through decades: As childhood memories merge with scenes of hospitals and pacemakers, Björk steps into the role of valiant “hopekeeper” for her mother while the clock ticks down (literally, there is a ticking clock in the song). I love Björk’s generous articulations of her mother—that Hildur’s dyslexia made her the ultimate improviser, the way her “vibrant rebellion” requires trilled Rs—but the more cutting lines are the things left unsaid or hard to face: “Did you punish us for leaving? Are you sure we hurt you? Was it just not ‘living?’” and “You see with your own eyes/But hear with your mother’s/There’s fear of being absorbed by the other.” It’s that push and pull of not wanting to lose your mother’s voice in your head, combined with not wanting to make her same mistakes.

Life cycles are at the heart of Fossora, whose title translates to a Latin feminine form of the word “digger.” The abstract a cappella interlude “Mycelia,” named for fungal root systems, is a beguiling mix of calm and hyperspeed that could soundtrack a time-lapse video of moss and mushrooms overtaking a forest. “Fungal City” moves the record toward the light of new love—but not too bright—with techno beats, bemused bass clarinet lines, and the supporting coos of serpentwithfeet (something of a musical hopekeeper himself). At times, Fossora’s mushroom-centric imagery can feel a little like an overwrought metaphor. But the theme of personal growth is inextricable from her mycophilia: She finds so much nourishment and possibility in the dark, mossy understory of life.

One standout, “Victimhood” conjures, with its creeping industrial-orchestral pulse, the folk terror of Ari Aster’s horror films; the lyrics are part shadow work, part feminist thought. Which is to say, the scariest thing I’ve heard on a record this year might be a half-dozen clarinet players, an industrial beat, and Björk’s voice weaving out of each ear with familiar phrases like “took one for the team.” She’s referencing a trap of womanhood, wherein being treated poorly makes you feel entitled to compassion, respect, sympathy. “Rejection left a void that is never satisfied/Sunk into victimhood/Felt the world owed me love,” Björk sings, and the only solution to transcending this archetype is a bird’s eye view. This level of reflection—an inventory of personal wounds bleeds into psychological self-evaluation and cultural context of women’s lives—is impressive on its own, but she sculpts the sound to mimic the disorienting, walls-closing-in sensation of questioning the story you tell yourself about yourself. It becomes a masterpiece.

Fossora’s final song, “Her Mother’s House,” is a meditative coda, a shift from grieving daughter to empty-nester, sung with her own daughter Ísadóra. The tone is peaceful—muted keyboard chords, curls of falsetto, a cor anglais solo—as Björk maintains the role of hopekeeper from afar. “When a mother wishes to have a house/With space for each child/She is only describing the interior of her heart,” she sings. At the end of the song, when she returns to the metaphor—“Her most loved ones already live in the chambers of her heart, the four chambers of the heart”—you can imagine her reaching out towards her ancestress, Hildur, who died from heart conditions.

In the lyric book, the last lines of “Her Mother’s House” are “curved buildings, matriarch architecture,” which is hardly audible in the recording, but that phrase—“matriarch architecture” is a handy one for considering Fossora and Björk at this point in her career. Matriarchy is not synonymous with new motherhood so much as the act of losing one’s mother, of assuming her role in the family and carrying on a specific legacy. And so, Fossora is not her mushroom record, her grief/hope opus, or even her Iceland album as she put it. It’s the sound of Björk building her home as the mother of it all.

%20Music%20Album%20Reviews.webp)

0 comments:

Post a Comment