On his third solo album in as many years, the wise and stoic singer-writer extolls the virtues of the sacred and the mundane.

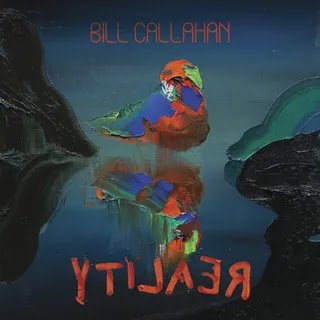

Over his last few albums, Bill Callahan has been pondering his role in the universe. Lover, father, son; marriage advocate, neighbor, cosmic tour guide. With each one he has edged closer towards some kind of essential purpose, embracing his sense of responsibility to his fellow man with a tentative joy, and radiating a euphoric humility about the idea that maybe there’s something even bigger out there. YTI⅃AƎЯ—rendered backwards like that—is Callahan’s third solo album in as many years (fourth if you count the impish covers album Blind Date Party with Bonnie “Prince” Billy), and you could interpret the 56-year-old songwriter’s newfound prolificacy as a desire to catalog every petal of his late blooming. As his family expands (he is now a father of two) and his marriage deepens, his roots grow longer and every second more precious. “I wrote this song in five and forever,” he sings on the uncommonly jaunty “Natural Information,” about boogying his infant daughter down the street, holding the moment and the lifetime that brought him here like some goofy sandal-wearing god spinning an orb in each hand.

Callahan specifically approached YTI⅃AƎЯ with the intention of rousing his listeners from our pandemic slumber and reacquainting us with life’s fundamentals: community, patience, deep feeling. It can be annoying, hearing someone extol the virtues of simplicity when times are anything but simple for most people, but Callahan—who we knew for decades as a dyspeptic, or someone doing a good impression of one—retains his irresistible convert’s zeal, one he wields to share the potency of fleeting beauty: Going “look, here” and letting us feel its weight. He watches his children hold hands on the dreamy “First Bird”—a rare moment of groundedness for his daughter, “because everybody wants to carry her around”; he lays on a rock and basks in the music of the spheres on “Planets,” which leaves him feeling as sparkling “as sudsy chrome/Renewed, ya know?/For a second season.” As with those images of buffed fenders and relieved castmates, he collapses the sacred and the mundane into his own particular kind of transcendence, one strengthened by an awareness of mortality: The gurney carrying his dying mother “screamed all down the hall/Just like a seagull screaming down the hall” on “Lily.” The shaggy, lightly noodling “Last One at the Party,” which might be about the late David Berman, makes the gnomic, yet somehow lovely promise: “If you were a house fire/I’d run back in for the cat.”

More than ever, the music reaches for transcendence too. These are Callahan’s most digressive and intuitive songs, and his finest work as a bandleader: guitarist Matt Kinsey, drummer Jim White, pianist Sarah Ann Phillips, and bassist Emmett Kelly at its core. The soothing “Planets” softly takes flight, reaching to echo that celestial resonance in softly shuddering electric guitar and a haze of cymbals; the conflict of dream-state and time’s lengthening shadow on “First Bird” prompt tender fanfares but then tense thickets of clarinet and guitar that wobble Callahan’s observations. Even the quietest songs teem with detail, which makes them feel alive. “I feel something coming on/A disease or a song,” he sings on “Everyway,” one of YTI⅃AƎЯ’s most grounded numbers and one of its most hyper-alert: a steady acoustic tumble that flickers with electric frequencies and barely perceptible cricket chirrups of guitar.

It yearns for the essential, even before Callahan explicitly articulates that aim. “And the wooden nickel we took/In the divorce of rider and course/Was by the book,” he sings later on that song, getting at one of YTI⅃AƎЯ’s main themes: the alienation of man from nature, and how they might be reunited. Callahan’s proposition is more metaphysical than straightforward prelapsarianism—think How to Do Nothing with a laid-back groove. In “Partition,” Callahan denounces “big pigs in a pile of shit and bones” who think they can buy enlightenment, and over the course of its driving, vigorous incantation, he urges us to: “Microdose!/Change your clothes!/Do what you’ve got to do …. To see the picture.” He practically vibrates as he does so, leaving you invigorated to wage your own quest for the sublime, whatever it may be. Though he doesn’t always land the pitch: “Natural Information” is a fun theme song for the virtues of the innate, but it’s so chipper—almost unsettlingly so, for anyone steeped in the Smog years—that it nearly lands in the territory of “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke.”

Callahan tempers his roving third eye with a less sparing lens on figures who are closed off to that sort of possibility, perceiving it as near enough the root of all evil. “Naked Souls” offers a comic sketch of basement-dwellers and keyboard warriors repelled by humanity—wearing their “shades that say ‘F-U’”—but then drives them out in a stormy climax of raging horns and communal singing, a bulwark against isolationism. The cool “Drainface” flashes with anger, seething against the patriarchal forces that appointed the kind of god that avenged cuckolding Adam by making “birth painful”; “Bowevil,” Callahan’s take on a traditional about warding off a harvest-chomping pest, scans as a rebuke of racists and xenophobes, though its wry, rumbling burr is too reminiscent of Apocalypse’s more stirringly ambiguous “America!,” or Gold Record’s entertainingly horrified “Protest Song,” to add much more than a dash of comedy.

YTI⅃AƎЯ reaches Callahan’s aims to reawaken something primal in his listener at its most diffuse—when it’s less a broadcast and more of a wavelength. The lazily lovely “Coyotes” is a domestic scene and a whole allegory. Callahan surveys his family on the porch while roaming dogs linger in the periphery—a little threat licking the edges of his perfect scene. In his sleeping hound, he sees the softening of the wild. In his family, he recognizes the pack mentality shared between man and beast. The only reading that wins out is Callahan’s deep, palpable contentment at the lot of it: “Yes I am your loverman,” he insists happily, again and again. That line aside, the sentiments on YTI⅃AƎЯ are less direct and specific than Callahan’s most openhearted love songs, such as Dream River’s “Small Plane,” which some listeners may lament the lack of; the melodies, too, are less emotionally leading and immediately satisfying. You get the impression those songs aren’t in his wheelhouse anymore; that instead, Callahan’s purpose, in this vivid season of his career, is to divine more nuanced shades of happiness, try to act as a conduit to that kind of connection, and leave a gap for us to fill in. It suits him.

0 comments:

Post a Comment