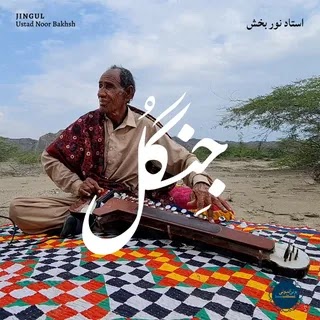

A revered musician in Balochistan, Pakistan, Ustad Noor Bahksh debuts internationally with a twangy, enveloping collection of reinterpreted and original compositions for the benju.

The benju is a twangy, droning keyed dulcimer that originated as a Japanese instrument called the taishōgoto. In the 1920s, Japanese sailors brought a toy version of the taishōgoto to Pakistan, where local musicians modified it, doubling its size and making it louder. Since then, the benju has become an integral part of the folk music from the Balochistan region of the country.

One of Pakistan’s most legendary benju players is Ustad Noor Bakhsh, who plays an electric version of the instrument on an amp powered by a car battery and a solar panel. He has long been regionally celebrated but only recently gained international acclaim when videos of his playing went viral earlier this year; in June, he performed live from Karachi for Boiler Room. Bakhsh’s debut album, Jingul, is a collection of four interpretations on Balochi poetry, shepherd’s tunes, and qawwali, plus one original composition. Throughout this electrifying project, the benju twists through sorrow, ecstasy, and epiphany, embroidering a vivid tapestry of emotion.

Much of the emotional impact of this music comes from its trance-like qualities. Bakhsh’s style of playing is frantic but also iterative: On “Bundar Nari,” his interpretation of a traditional flute song, he embellishes on one twinkling refrain over and over until it feels like a meditation. “Jingul,” an original composition inspired by the sounds of the birds in the jungle near his home, is similarly repetitive but more assertive: The benju spirals over a pounding backbone established by the damboora, the two-stringed lute that is the only other instrument on the album. Thanks to the vigor and confidence of his playing, listening to Bakhsh circle a few notes is an enveloping experience.

One of the album’s most melodious song is “Shahbaz Qalandar,” a shortened interpretation of a classic qawwali song, “Dama Dam Mast Qalandar.” The instrument sounds incandescent here, like light refracting on fresh snow. As ruminative and heady as Bakhsh’s music often is, “Shahbaz Qalandar” shows that he’s just as compelling when his delivery is playful and exploratory.

Jingul was recorded live at sunset, and the poignant melancholy of dusk permeates the music. The metallic, plucky sound of the benju is distinct, as are the particularities of Bakhsh’s trills and cascading improvisations. But the ethos that guides these compositions—the unending pursuit of beauty, the simultaneous embrace of sorrow and transcendence—is familiar. You might find it in the astral harp music of Mary Lattimore, or the kaleidoscopic guitar playing of Mdou Moctar. It’s the kind of music that leaves you grasping for the spiritual and indefinable, that burrows into your soul and glows there.

0 comments:

Post a Comment