Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the major-label debut from the sludge-metal pioneers, an album that marked their transition from rockers to experimentalists.

Even as a kid, Buzz Osborne had the hair: that splendid shock of aerodynamic curls that rose above the crowd like a sail at the 2010 World Series playoffs, a crown befitting the name King Buzzo. Born in the remote Washington lumber town of Morton, Osborne moved around the state with his dad, who worked in the timber industry, before the family settled in Montesano in coastal Grays Harbor County. Twelve-year-old Osborne was an outsider: a new face in a tight-knit community, a musical omnivore in a place where record stores were nonexistent and playing the high school dance was the peak of most musicians’ ambitions. The hair didn’t help. “He was a freak and no one liked him,” said Matt Lukin, one of the first like-minded kids Osborne met in Montesano, with whom he’d form one of the Northwest’s most influential heavy rock bands, the Melvins.

Osborne’s dad wanted him to sign up for the Army, but when Buzz fell sick he went to the local recruiter’s office and got a permanent excuse from service; instead, he got a job at the local Thriftway, where a disliked employee named Melvin became the inspiration for the name of his band. He met Lukin at Montesano High School, and their social circle would expand to include Osborne’s coworker Mike Dillard and a couple of kids named Kurt Cobain and Krist Novoselic. During this time, Osborne positioned himself as a relentless rock’n’roll evangelist, spreading the gospel of ’70s groups like Kiss and Cheap Trick and punk bands like Black Flag and MDC to his friends. He burned compilation tapes, made pilgrimages to the DJ’s Sound City record shop in nearby Aberdeen to talk music with clerk Tim Hayes, and even wrote an article for the Montesano Vidette arguing the value of small shows; years later, Novoselic would credit him with bringing punk rock to their community.

When Osborne formed the Melvins in 1983, with Lukin on bass and Dillard on drums, he found a new vehicle for his crusade—and a way out of Montesano, as the band started gradually playing gigs closer and closer to the nearest major city, Seattle. The Melvins played covers of Jimi Hendrix, the Who, and Osborne’s beloved Kiss, mixed in with fast hardcore punk. That changed in 1984, when Black Flag confounded their fellow punk rockers by concluding their album My War with three six-minute-plus tracks that pulled away from the breakneck speed of hardcore toward the wounded crawl of doom metal.

Black Flag were enjoying an absurdly productive year, releasing three albums (starting with My War) and playing roughly 170 shows. One of these shows was September 25, 1984 at the Mountaineers Hall in Seattle, with a hungry young band called Green River opening. Osbourne, Cobain, and Lukin all went, with Cobain selling his entire record collection to buy tickets. None of them emerged the same. Cobain started spiking his hair, spray-painting cars, and screaming to strengthen his vocal cords. As for Osbourne and Lukin: “The Melvins went from being the fastest band in Seattle to the slowest, almost overnight,” in the words of another Washington punk named Kim Thayil, who would form a band called Soundgarden that same year.

By this time, the Melvins had replaced Dillard with a drummer named Dale Crover, whose mother’s house in Aberdeen made for a makeshift practice space. The fledgling C/Z Records picked them up and put them on a 1986 compilation called Deep Six that was meant to highlight the new sound brewing in the Northwest, but after cutting 1986’s self-titled EP for C/Z and 1987’s Gluey Porch Treatments for Bay Area label Alchemy, Osborne and Crover moved to San Francisco. Lukin alleges that Osborne declined to formally fire him, telling him he’d broken up the band; it wasn’t until Lukin ran into Osborne in San Francisco that he learned the truth. (Lukin would go on to co-found Mudhoney, then retire from music to pursue carpentry.)

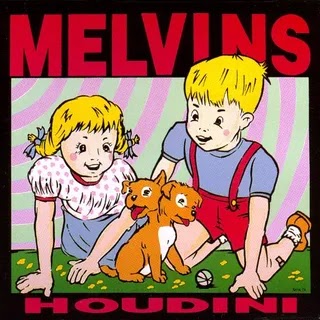

The Melvins’ early years in the city produced some of their best work: Ozma and Bullhead, with Lori Black (the daughter of Shirley Temple, of all people) on bass, and the mighty drone-metal ur-text Lysol, with Joe Preston holding down the low end on an early entry in one of underground metal’s most enviable resumés. Meanwhile their old buddies Cobain and Novoselic were building steam fast in Seattle, exalting the influence of the Melvins at nearly every turn. “You couldn’t buy better advertising,” said Osborne, and soon, major labels intent on snatching up as much of the Seattle sound as they could were looking to this manifestly, militantly bizarre band in hopes they might be the next Nirvana. The Melvins went with Atlantic and booked San Francisco’s Brilliant Studios to make their fifth album, 1993’s Houdini.

If the industry climate was ideal for a band like the Melvins finding an inkling of commercial success, the band’s personal circumstances were not. By the time they started working on Houdini, they’d fired Preston and taken Black back on, but she checked into rehab after being busted for heroin possession in Portland, and Osborne and Crover played bass on most of the album. Meanwhile, ostensible “producer” Cobain was deep into his own heroin addiction and consumed with the making of Nirvana’s In Utero, released on the same day as Houdini. Originally scheduled to workshop songs with Osborne before production, he flew into San Francisco on the first day of sessions and was asleep by 6 p.m. “I went to [Nirvana manager] Danny Goldberg’s office in L.A. and said, 'Look, Kurt Cobain’s strung out,’” Osborne said. “Kurt was really bad, as bad as he’s ever been.”

Houdini’s status as the best-selling Melvins album no doubt owes a lot to Cobain’s name on the sleeve. Yet its status as the most beloved Melvins album speaks to how well the band weathered these circumstances. Houdini isn’t a blown opportunity, nor does it sound like a stab at the charts. For the most part, it sounds like the album they might have made if they’d still been bouncing around Bay Area indie labels. The Melvins made a habit of working fast and loose, usually banging out albums in a few days. Osborne often made up the words to his songs on the spot, and the lyrics on Houdini are gloriously impenetrable. It’d be easy to totally dismiss them as phonetic gibberish if not for the presence of a lyric sheet in the liner notes. Say it with me now: “Los ticka toe rest!”

There could be an objectively correct interpretation of these songs somewhere in Osborne’s head, but he’s at no great pains to share it with the listener. If a song like “Night Goat” seems to be about sex, not every verse has to corroborate that interpretation, and if “Sky Pup” finds Osborne affecting the nasty nasal tone people use when they’re making fun of someone else, it’s more likely that that’s just how he decided to sing that day. Osborne’s approach to songcraft brings to mind Magma singer Klaus Blasquiz’s explanation of his outré French avant-rock band’s self-invented phonetic language: “The language has of course a content, but not word by word.” There’s a fearsome purity to these songs, free of context, existing only to be themselves.

With the vocals free from the obligation of meaning anything, the Melvins invite us to listen to what’s going on with the guitars and drums, particularly the latter. Dale Crover’s role is more architectural than anything else. “Hooch” begins with a Bonhamesque clatter that simmers down to a single kick drum before the voice and guitar enter; the two tom hits that punctuate Osborne’s first two lines feel as crucial to the song’s meaning as anything out of the singer’s mouth. The riff cycles between a few basic power chords; Crover is really the soloist. “If the drums were different, the song wouldn’t be as good,” Osborne admits. “It’s effective because of the dynamics of the way the drummer plays.”

The brilliance of “Night Goat” lies in the way the drumbeat never gets off the ground—it always seems to be stuck in dead space like the metal equivalent of a TV “breaking news” theme, anticipating nothing. There’s a bit on “Lizzy” where the riff is accompanied only by Crover’s woodblock, and those hollow thunks on the off beat somehow sound significant, even if you can’t place your finger on why. “Hag Me” is so slow that it feels beatless, almost ambient; it’s this album’s answer to Bullhead’s “Boris” and Lysol’s “Hung Bunny,” a glacier moving under its own weight. It’s no coincidence that Crover’s most straight-ahead rock beat comes on a holdover from the circa-1983 Mike Dillard days—nor can it be a coincidence that the song in question is called “Set Me Straight.”

If there’s anything everyone can agree on about the convoluted credits for Houdini, it’s that Cobain played on two songs: “Sky Pup” and the 10-minute closer, “Spread Eagle Beagle,” which consists entirely of percussion. “It’s cool, but I’ll never listen to the whole thing,” Osborne said of the latter, and it’s easy to understand why. This is no “Moby Dick” or “Toad.” Instead of building to a climax or playing rhythmic tricks on the listener, “Spread Eagle Beagle” clatters obstinately until the distances between the drum thwacks grow so long that it’s almost as if you’re listening to a parody of CD-era albums whose bonus tracks come after a long silence. Listeners are likely to ask “is it over yet?” for more reasons than one.

It speaks to the talent and work ethic of the Melvins that they were able to come out of the strange, sad circumstances of Houdini’s making with an album that feels like the logical next step in their career. But it’s also hard to shake the feeling that had the Melvins actually spent some time with Cobain or a more reliable producer working this thing out, they might’ve made a better record. Bullhead and Lysol are tighter, and the Melvins sound much more comfortable on their second Atlantic album—1994’s sensual, atmospheric *Stoner Witch—*whose ambient and noise experiments are far more purposeful and enjoyable.

Houdini feels both definitive and transitional. It’s definitive because “Hooch,” “Night Goat,” “Lizzy,” “Hag Me,” and the mid-tempo bruiser “Honey Bucket” rank among the band’s best songs, and because it shows them at the peak of their powers as a pure metal band while hinting at their budding experimental impulses. It’s transitional because it’s the last album they’d make before they’d let those impulses take over. “Spread Eagle Beagle” is more interesting as a prank than as a piece of music, and “Pearl Bomb” lives and dies by its curious stuck-typewriter percussion track, but they would predict the Melvins’ output for the subsequent decade, starting with their next album, 1994’s Prick, made in an adulterous coupling with Amphetamine Reptile while still on Atlantic—and home to such songs as “Pure Digital Silence,” which is exactly that.

By Stoner Witch, the deliberately prankish Atlantic swansong Stag, and their first post-Atlantic album, Honky, these left turns would be a crucial part of their sound. Their music since then has generally bounced between variations on their early heavy-rock sound and diversions both fascinating (the wintry, underloved Honky or the electrifying remix album Chicken Switch) and grating (their predilection towards jokey covers like “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” or, infamously, “Smells Like Teen Spirit”).

The Melvins are still active and prolific, even if their inability to hold down a bassist has become such a running joke that 2016’s Basses Loaded built its whole concept around juggling six current and former Melvins on low-end duties. As indelible as their impact on Northwest rock was, it seems like a small part of a career that’s placed them at the center of the Bay Area’s stable of art-metal oddballs, centered on their longtime home of Ipecac and its boss Mike Patton, and as pioneers of sludge metal, which is more true to the Melvins’ original Black Flag-meets-Black Sabbath vision than the music Nirvana would become famous for.

Given the Melvins’ refusal to compromise their sound and disgust for “rock stars” and institutions such as the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, it’s hard to imagine they’d be happier if they were a Seattle success story than in their present role as a hardworking cult band. Houdini ultimately sold 100,000 copies, and the band even cracked the Top 200 with The Bride Screamed Murder in 2010, but they have no hits to begrudgingly play for casual fans, no single towering underground classic hanging like an albatross. In a 2012 interview after taking the stage at the Loft in Atlanta, Osborne expanded on a philosophy that hasn’t changed since he exalted the values of tiny punk shows in the Montesano Vidette. “This is about as big as I like to go,” he said of the 650-capacity venue. “You can see from everywhere; you don’t feel like you’re in some airplane hangar. There’s a reason I liked punk rock to begin with. I haven’t forgotten that.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment