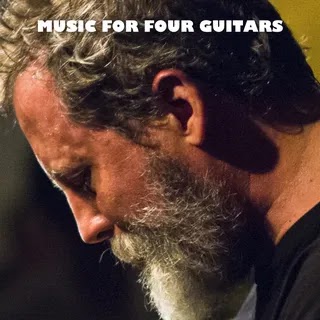

The veteran improviser creates a virtual quartet indebted to classical minimalism and avant-garde guitar ensembles, sculpting multitracked figures into complex systems.

Bill Orcutt’s career has been as winding as his approach to the guitar. Formerly of the Miami noise group Harry Pussy, he has played free improv with musicians like percussionist Chris Corsano, recorded a string of solo guitar records, and even coded open-source software. On Music for Four Guitars, he takes another new direction. It’s a rigidly structured quartet for multitracked electric guitars that weaves tiny rhythmic phrases into expansive tapestries, drawing on the tenets of early minimalism and New York guitar groups like Glenn Branca Ensemble, and adding bluesy riffs and taut, distorted tones to the mix.

Orcutt was inspired to create a guitar quartet a few years ago after a conversation with guitarist Larry Manotta. While that project never manifested in its original form, Orcutt held on to the thought of one day writing for an ensemble, an idea that eventually became Music for Four Guitars. Orcutt plays all four parts on each song, and while all 14 tracks are relatively short—just two or three minutes apiece—they grow into intricate, brightly hued lattices that feel much more expansive than their relative brevity might suggest.

The songs unfold in similar ways: Short melodic fragments accrue in layers to form a web of earworms. Each track grows from a single phrase into an interwoven network in which each motif is in conversation with the others. Orcutt’s structures are indebted to minimalism’s interest in the way that repeated figures, when echoed and entwined, can transform over time. In its relentless drive and emphasis on repetition, it’s reminiscent of pieces like Steve Reich’s Electric Counterpoint or Philip Glass’ Two Pages. But while this general pattern reappears throughout Music for Four Guitars, it doesn’t become monotonous—instead, Orcutt brings a kinetic, improvisatory spirit to his pieces.

Despite the music’s meticulousness, it’s the moments where Orcutt throws in twists and turns—and leans into sharp distortion—that make it feel alive. Tracks like “In profile” begin with a simple, oscillating melody and grow into a maze of tangled dissonance. Here, instead of letting pieces snap together like a jigsaw puzzle, Orcutt leans into tension, letting lines collide and harmonies crunch. Elsewhere, his pursuit of the drone takes him to some far-flung places: The clanging “Only at Dusk” recalls the hypnotic expanses of no wave, while the trills of “On the Horizon” might suggest Tuareg desert blues.

While stern, pummeling loops serve as the album’s backbone, it still takes some unexpected turns. “In the rain” beams like a ray of sunshine with its bouncy, folksy air, while closer “Or head on” sends the album off in a rainbow of colors with radiant strums. The rigorous patterning of early minimalist composition is just a starting point for the snakelike paths Orcutt ends up taking. At its heart, this music might be all about structure, but it’s also about listening to patterns evolve, celebrating the journey that leads wherever the music wants to go.

0 comments:

Post a Comment