The rapper’s second greatest hits compilation collects some nice singles, but mostly feels like the portrait of a wayward artist who’s spent the last 13 years going in every direction.

In his prime, controversy was Eminem’s secret sauce. As a white rapper with bottle-blonde hair and boy-band looks who liked to joke about indoctrinating children with antisocial thoughts, Slim Shady was the straw man onto which square America projected its most deranged insecurities about the fragility of its youth. He was so good at his job that by the time he dropped Relapse—his 2009 comeback record following years of heavy pharmaceutical use—his most violent bars now just felt like the work of an institutionally entrenched artist playing the hits. After all, millennials who’d listened to Eminem’s early records in middle school were by then in various stages of young adulthood, and most of us turned out fine.

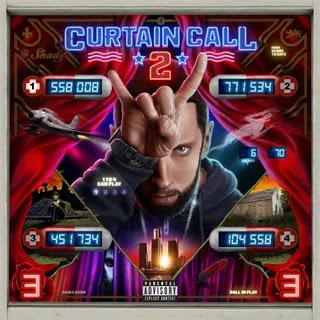

So as he entered his second decade of fame, Eminem adopted a new identity: an extremely famous, super-intense dude who rapped really complicated raps. But beyond this basic foundation, he became a chimera, his body of work an assemblage of often disparate personas, subject matter, and sounds. At times, he’s chased trends and tried to reinsert himself into the zeitgeist; at others, he’s retreated inwards, reflecting on his legacy or finding yet another way to recreate past selves. That his music lacks perspective or personality beyond the fact that listeners immediately know that it’s Eminem rapping hasn’t hampered him from becoming the best-selling singles artist of all time, and it certainly hasn’t kept him from continuing to be a reliable hitmaker. But these qualities make Curtain Call 2, a double-disc compilation of his post-comeback greatest hits, feel like a portrait of an artist who’s spent the past 13 years going in every direction.

Eminem has made some great music during this era—tracks like Revival’s “Offended,” an off-kilter lyrical workout over a tightly wound Charles Bradley loop; his guest spot on Nas’ “EPMD 2,” in which he delivers a reverent ode to the golden age of hip-hop; Relapse’s “Deja Vu” which combines the fearless inventory-taking of 12 Step programs with blistering internal rhymes. There’s probably a Spotify playlist out there that’s scrounged up the best of Em’s latter-day catalog and uses it to make a case that, despite one lackluster album after another, Eminem is still capable of reminding us why we used to stan the guy who coined the term “stan.”

But rather than panning for gold in the mud, Curtain Call 2 contents itself with being a damningly accurate reflection of what Eminem’s been up to lately. He gives us goopy pop songs like “Lighters” and “Nowhere Fast,” and maudlin deconstructions of toxic relationships like “Love the Way You Lie” and “Headlights.” There are anthems for personal uplift and/or weightlifting (“Not Afraid,” “Cinderella Man,” and “Phenomenal”) and the Rick Rubin and DJ Khalil-enabled dalliances with rap-rock (“Berzerk,” “Won’t Back Down”). It’s topped off with a song about killing people (“3 a.m.”) and one about how tough it is to be Eminem (“Walk on Water”), with some r/hiphopheads-baiting fast rap (“Rap God,” “Godzilla”) thrown in for good measure. Listening to 34 tracks of this stuff in a row—especially considering that Eminem was one of the last major rappers to cut overtly homophobic language out of his rhyme book—is a grim experience. By the time Ed Sheeran shows up on Disc 2, his vocals feel like the sweet release of death.

In his best work, Eminem ushered listeners into his world and forced them to engage with his music on terms that he set. He could “murder a rhyme, one word at a time,” or interrupt a string of “vile, venomous, volatile” invective to make a bunch of chainsaw noises. He cultivated a sense that everything he did was a dart shot into the eye of a culture industry that decried him while profiting off his infamy. Though post-comeback Em was never going to be the cultural firebrand he once was, there was no reason he needed to let go of his auteurist vision. Yet after the relatively insular Relapse, he increasingly farmed out hooks to a rotating group of singers with varying abilities to not make his own voice sound like nails on a chalkboard by comparison. He also stopped rapping over instrumentals custom-tailored for him by either Dr. Dre or longtime collaborators the Bass Brothers, instead leaning on his own productions or sourcing tracks from whichever beatmakers the rest of the industry was using at the time. This all had the effect of making Eminem sound generic, and it coincided with the accelerating pace of his raps, creating more opportunities to toss dreadful puns and abject filler into his songs.

Despite showcasing some of Eminem’s stylistic growing pains, Curtain Call 2 isn’t completely lined with duds. “Godzilla” has always been a jam, in part due to Em’s vocal chemistry with his posthumous guest Juice WRLD, but also because it’s a song where Eminem actually sounds like he’s having fun. “Fast Lane,” off Eminem’s Hell: The Sequel EP with Royce Da 5'9'', approaches the standard of quality that the duo established for themselves the first time around. Now that it’s a few years removed from radio ubiquity, “The Monster” finally has room to luxuriate in its massive Rihanna-driven hook. As for the new material on here, it’s fine. Eminem raps way harder on “The King and I” than seems necessary for a track originally featured on the soundtrack to Baz Luhrmann’s movie about Elvis, yet it’s nice to hear him actively engaging with an artist with whom he’s drawn pointed comparisons over the years. And if you can ignore its Bored Ape Yacht Club tie-in music video, his reunion with Snoop Dogg on “From the D 2 the LBC” offers one of Eminem’s best self-produced beats in years, as well as an opportunity to hear two legends try to out-rap each other.

In an illuminating 2017 interview with Vulture, Eminem admitted that at times he’s vexed by his own audience, attempting to “give them the old Eminem” only to feel that his fans believe “he’s too old to be rapping about that kind of shit.” (By now, he’s so many years past his cultural peak that he recently admitted that he literally forgot about Dre.) As he’s aged, Eminem has further disappeared into his craft, putting together verses so intricate that rapping along with them is almost physically impossible. Where he once deployed his skill strategically, he now uses it as an end unto itself. Take “Rap God,” whose Max Headroom-indebted music video currently sits at just under 1.3 billion YouTube views. The song set a Guinness World Record for the most number of words contained in a hit single, cramming 1,560 of them into approximately six minutes. You don’t have to know the slightest thing about hip-hop in order to understand that what he’s doing in the track is astonishing, but “Rap God” is less a work of art and more a piece of content you consume because of the sheer fact that it exists, like a TikTok of a dude expertly navigating the world’s longest parkour course.

It says a lot about Eminem’s run in the 2010s that he sounded most on-task in “Killshot,” a diss track against Machine Gun Kelly, of all people—and it’s equally telling that though Em won the battle by lyrically grinding the Cleveland upstart into a pulp, all the once and future king of pop-punk had to do to win the war was rap “his fuckin’ beard is weird” and then stick out his tongue like a demonic Bart Simpson. When Eminem released the first Curtain Call in 2005, it was a fitting victory lap for a guy who’d spent the better part of six years reshaping American culture. The hits lining Curtain Call 2, meanwhile, feel more like that same rapper running up the score just because he could. Eminem turns 50 in October, and as he enters the next stage of his career, he’s more than earned the right to be himself in his music. If at this point his listening public has only the haziest sense of who he actually is, that could prove to be an asset. Perhaps when he releases Curtain Call 3, it will tell the story of how we got to know Eminem all over again.

0 comments:

Post a Comment