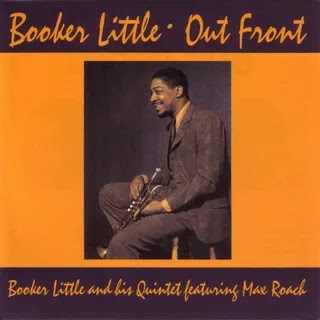

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit a crucial jazz record from 1961, led by a lyrical trumpeter and composer who captured the many overlapping currents of the genre.

At the dawn of the ’60s, jazz was in the midst of a growth spurt that doubled as a culture war. Ever since Ornette Coleman’s 1959 debut at New York’s Five Spot—a gig that’s often viewed as the official unveiling of free jazz—critics and artists had been fretting over the future of the genre like parents of a wayward teen. Much like when bebop swept the scene in the mid-’40s, the prevailing sentiment was that you had to pick a side. Were you a defender of the jazz faith, or a champion of its latest modernist turn?

At least one thoughtful young musician, trumpeter Booker Little, wasn’t buying the binary. As he put it in a 1961 interview, if jazz were mapped on a political spectrum, he’d fall somewhere in the center. “My background has been conventional,” the conservatory-trained 23-year-old told the writer Robert Levin, “and maybe because of that I haven’t become a leftist, though my ideas and tastes now might run left to a certain degree.” He went on to defend Coleman (“…I think I understand clearly what he’s doing, and it’s good”) before touching on one of his core aesthetic tenets. For Little, dissecting an artist’s methods without considering the feelings that informed them made no sense. “I can’t think in terms of wrong notes,” he said. “Because if you insist that this note or that note is wrong, I think you’re thinking completely conventionally—technically—and forgetting about emotion.”

These beliefs were crystallizing at a critical time for the trumpeter. Tragically, he wouldn’t live to see 24—in October 1961, he died from uremia, essentially blood poisoning due to kidney failure. But before his death, he would back up his statements with an album that made the post-Ornette jazz wars seem petty and myopic. Out Front, his third LP as a leader, recorded in two sessions in the spring of ’61, didn’t feel remotely like free jazz. But it crackled with a Coleman-esque charge thanks to the saxophone work of Eric Dolphy, who in 1960 had recorded alongside Ornette on the album that would become the flagship of that movement, and would soon take part in John Coltrane’s most adventurous work to date. Nor did it fit in with the hard-bop sound that defined the jazz mainstream at the time, where fellow rising trumpet stars Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan (both born, like Little, in 1938) each found a comfortable home. Yet at moments it swung as hard as a typical contemporary Blue Note recording.

It didn’t exemplify any other trending jazz topics of the time, either: spacious modal jazz à la Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue; the classical-fusion movement known as Third Stream; Dave Brubeck’s rhythmic experimentation as heard on Time Out. But Out Front’s sound—marked by elaborate arrangements featuring piquant harmonies and ever-shifting time signatures, occasionally broken up by moments of startling minimalism—felt just as fresh as any of those developments.

Out Front was simply Booker Little music. And if the goal was to bring a composer’s touch to jazz while keeping emotional expression at the forefront, few statements in the genre—and even fewer outside the catalogs of, say, Duke Ellington or Charles Mingus, both of whom the trumpeter cited as key inspirations—can rival it. (Candid, the label that originally released Out Front, will reissue it in a remastered vinyl edition later this month.) What Ellington realized with a big band or Mingus a midsize ensemble, Little achieved with a sextet. “Moods in Free Time,” maybe Out Front’s quintessential track, shows just how much he could accomplish in that format, summing up the Booker Little soundworld in just under six minutes. It starts out feeling orchestral, with Little leading his band—including Dolphy; Max Roach, the pioneering bebop drummer and Little’s first major employer; trombonist Julian Priester; pianist Don Friedman; and, on this track, future bass legend Ron Carter—through a tightly plotted overture. The horns trace distinct but interlocking paths through a complex multi-part theme that cycles through various rhythms—including a prominent section in 5/4, a favorite meter of Little’s that shows up all over Out Front. As crisp and driving as the arrangement sounds, the harmonies have a slightly sour, mournful quality, reflecting Little’s love of the tastefully outré. (“In my own work I’m particularly interested in the possibilities of dissonance,” he told Levin. “The more dissonance, the bigger the sound.”)

In a typical jazz tune of the time, following this “head,” you’d expect a series of solos on the same form. But right around the one-minute mark, the piece downshifts into a dirge, with the horns sobbing out a painfully slow background pulse as Little improvises aptly yearning lines, maintaining his trademark tone—rounded and gorgeously pillowy—even as he cranes for piercing high notes. Roach, a master of vigorous swing, sets aside a timekeeping role entirely and draws on his classical percussion background to conjure eerie whooshing-wind sounds from a set of timpani drums. When Dolphy enters on alto sax, the vibe changes from somber to downright harrowing. Ushered in by dramatic mallet strikes from Roach, he plays a shuddering, eruptive phrase, setting up what feels less like a jazz solo than some kind of sonic Butoh, where long, jagged swoops and wobbling squawks collide with bluesy punctuations. Once Dolphy finishes, Roach switches back to the kit for a brief, sharply etched solo that reestablishes the feel of the intro, and the band comes in for a reprise of the initial theme. Taken as a whole, “Moods” is bizarre yet breathtaking—a through-composed musical manifesto that perfectly balances compositional intrigue with an outpouring of visceral feeling.

How is it that Little had already staked out such rich aesthetic terrain at such a young age? His early background offers some clues. Little’s mother and father both played music in church; his sister, Vera, sang opera and enjoyed a long, distinguished career in Europe. In 1959, she sang Bach at the Vatican, becoming the first-ever Black singer to perform for a pope. Little started playing trumpet while attending Memphis’ Manassas High, where he formed close bonds with future jazz greats like pianist Harold Mabern and saxophonist George Coleman. In his autobiography, Miles Davis made reference to “the great young trumpet player Booker Little,” and wrote of this Manassas cohort, “I wonder what they were doing down there when all them guys came through that one school?”

Little went on to study composition, theory, and orchestration at the Chicago Conservatory. While there, he met rising saxophone star Sonny Rollins, who stressed to Little the importance of finding one’s own sound, and also facilitated his first high-profile gig by introducing him to Roach. In 1958, the drummer—who’d previously worked with another young trumpet star, Clifford Brown, before Brown’s death in a 1956 car accident—hired Little for his working band, which also included the trumpeter’s old Memphis pal George Coleman. Little quickly established himself as a star soloist with Roach, but his writing made an equally strong impression. On pieces like “Larry-Larue” and “Gandolfo’s Bounce,” Little compositions that showed up on Roach’s albums during his tenure in his band, you can already hear him using a jazz quintet with three horns as a mini orchestra. Little’s own debut album, 1958’s Booker Little 4 and Max Roach, featured just two horns—his trumpet and George Coleman’s tenor—but achieved a similar effect.

The next couple years were a flurry of activity for Little. He made a powerful and assured quartet album under his own name; recorded more sessions with Roach, including the groundbreaking civil-rights-movement–inspired We Insist! and an all-star date held in protest of the Newport Jazz Festival, which featured a brilliant Little original; and tracked his first date with Eric Dolphy. Things ramped up majorly in 1961: In February, he re-teamed with Roach, We Insist! producer Nat Hentoff and the Candid label on singer Abbey Lincoln’s Straight Ahead. The album features two pieces arranged by Little, including “In the Red,” a chilling evocation of, as he puts it to Hentoff in the liner notes, “that awful suspense you’re always in when you’re broke.” With its crawling tempo and tense harmonies, it plays like a prelude to Out Front—the clearest statement yet of Little’s expressionistic vision.

But Out Front, recorded in March and April of ’61 and also produced by Hentoff, was where everything clicked into place—the first album-length immersion into the trumpeter-composer’s heart and mind. In line with "Moods in Free Time," the full LP has an uncommon gravitas. On “Strength and Sanity,” one of several downtempo pieces on the album, Don Friedman’s romantic piano intro and Roach’s whispery brushed cymbals set the table for a classic jazz ballad, but the composition refuses to settle down. After two minutes of gently unspooling melody, the rhythm section drops out and the horns play a kind of wounded fanfare, where Dolphy’s alto and Priester’s trombone frame Little’s trumpet in deep ochre tones. Little goes on to play a lovely extended solo with soaring peaks, but the heaviness of the arrangement—its sense of being suspended in a persistent existential ache—never subsides.

“Man of Words,” dedicated to Hentoff and paying tribute to his profession, is another pensive masterpiece. Played without drums and featuring Ron Carter on bowed bass and Dolphy on bass clarinet, it employs an incredibly simple arrangement to awesomely intense effect. The entire piece, just short of five minutes, consists of a droning, descending melody, repeated over and over, with roomy pauses in between. Little is the only soloist, and his phrases are both precision-sculpted and filled with pathos. He builds steadily from slow arcs and pirouettes to an arresting climax: Right around the 3:40 mark, he plays three pulsing, almost gasping high notes. The last one, which rings out while the rest of the band is silent, feels like some kind of sonar ping into the abyss.

There’s also optimism on the record, as on hard-swinging opener “We Speak,” where Little’s bold, proudly ornate writing feels more anthemic than reflective, and “Quiet Please,” which repeatedly zig-zags between slow and fast, portraying the struggle of a parent trying to keep a rambunctious child quiet. (“He’ll obey for a few moments, but he’s quickly active and roaring again,” Little, already a young father by then, told Hentoff in the liner notes.) The accelerating structure of the piece inspires thrilling quicksilver alto runs from Dolphy.

Out Front possesses a rare kind of self-assurance, a staunch commitment to an unusual vision that demands full engagement from both the players and the listener. Around the time Little recorded these pieces, as Coleman, Dolphy, and others were spearheading the emerging jazz avant-garde, his peers Lee Morgan and Freddie Hubbard were releasing albums packed with catchy, swinging tunes that presented them as star soloist-bandleaders. Out Front features plenty of virtuosic playing, but its fireworks are secondary to its shifting moods and sonic curveballs. The album feels more like a suite tailored for a concert hall than a set that would translate well to a nightclub.

But Little wasn’t having any second thoughts; he knew he’d found his direction, and that Out Front was a breakthrough. “I don’t think there’s very much of my work prior to these Candid albums that expresses how I feel now about what I want to do,” he told Levin after recording the LP. He had lots of ideas about upcoming projects, including a possible multimedia work involving visual art and an album that featured tenor-sax giant Coleman Hawkins in what Little termed “a modern setting.”

Meanwhile, right after the album’s second session, he got back to work. In May and June of 1961, he recorded with John Coltrane on what would become Africa/Brass, the first album of the saxophonist’s legendary Impulse! Records run. In July, he and Dolphy spent two weeks co-leading a band at East Village club the Five Spot; one full night was recorded, yielding an electrifying pair of live albums. In August he made his last recordings with Max Roach, which would end up on the drummer’s Percussion Bitter Sweet, an album filled with rich arrangements that seem to point back to the orchestral feel of Out Front. And either that month or in September—the precise date is fuzzy—he made one final album under his own name: Booker Little and Friend, later reissued as Victory and Sorrow, the title of the opening piece.

That fall, apparently just days before his death, Booker Little visited the office of Down Beat magazine and gave an interview. Only one quote was ever published, but that brief statement was enough to capture how much determination he still had in him, and how certain he was about his creative direction—that unique weave of improvisational pathos and compositional sophistication that came to full flower on his recordings that year. “Writing is a special thing with me,” he said. “I want to play, but I am very interested in writing because I hear so many things for others. I’ll develop, I need to, and I’ll do it in my own way. I’ll always be me in the important part that’s me. The other part, the part people buy, that’s different. I’ll still always be me, even there. You can’t sacrifice integrity and still be you.“

In his liner notes to Out Front, Nat Hentoff pointed out a slight paradox in the album’s title. “In Out Front, Booker Little is actually not at all ‘far out’ in the usual sense of that term,” he wrote. “He is, on the contrary, a strongly self-disciplined creator of forms that follow his own inner feelings.” It’s a smart read: As both his music and his words show, Little wasn’t necessarily aiming to revolutionize jazz in the way that Ornette Coleman already had or John Coltrane soon would. Maybe for that reason, coupled with the fact of his untimely death, Little’s influence has been limited—though in the six decades since his death, other trumpet luminaries have made a point of keeping his legacy alive. Freddie Hubbard included a lovely ballad dedicated to his peer and friend on Hub-Tones, recorded almost exactly a year after Little’s passing; Dave Douglas, Kenny Wheeler, and Nicholas Payton each composed tributes to Little in the ’90s and early 2000s; and in 2017, new-school star Jaimie Branch singled out Little as “by far my favorite trumpet player.”

Booker Little wasn’t a rule-conscious conservative, nor an iconoclastic “leftist,” but some artful weave of the two, intent on using music to explore his own distinct blend of beauty and anguish, victory and sorrow. Thankfully, before he left us, he found the courage to look beyond all the furor over right and wrong notes, zeroing in instead on the ones that simply felt the most true.

0 comments:

Post a Comment