Capturing the sound and spirit of its time, this compilation of demos and home recordings showcases the mellow, genre-blurring taste of ’70s record man Earl McGrath.

Earl McGrath can’t be called a household name. Even among music aficionados, he’s a bit of an obscure figure. A close friend of Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun, McGrath ran two subsidiaries of the label: Ertegun gave his pal Clean Records in 1970, then McGrath parlayed a friendship with Mick Jagger into a position at the head of Rolling Stones Records in 1977. McGrath departed Rolling Stones Records in 1980 and left behind the music industry, returning to what he did best—cultivating friendships and facilitating ideas among the elite. Maybe the public at large wouldn’t have recognized McGrath. Still, he along with his wife Camilla Pecci-Blunt—an Italian countess who was a descendent of Pope Leo XIII, the head of the Catholic church at the dawn of the 1900s—were linchpins of high society in New York and Los Angeles, calling everyone from Harrison Ford to Joan Didion lifelong friends.

McGrath died in 2016, nearly a decade after Camilla. After his passing, journalist Joe Hagan received an invitation from his estate to peruse pictures Camilla photographed for possible inclusion in his biography of Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner. While he was there, he stumbled upon a cache of reel-to-reel tapes squirreled away in a closet. Within the roughly 200 tapes were unheard documents of McGrath’s time as a record man, a period that spanned the entire 1970s. Among those tapes were some Rolling Stones rarities—outtakes from Emotional Rescue and live recordings of the New Barbarians, the short-lived busman’s holiday from Keith Richards and Ron Wood—along with the master tape to Peter Tosh’s “(You Gotta Walk) Don’t Look Back,” but this wasn’t just a stash of Rolling Stones Records artifacts. There was a wealth of recordings from earlier in the ’70s, notably some of the first work from Daryl Hall and John Oates, as well as tapes from the tail end of the decade, including material from punk poet Jim Carroll.

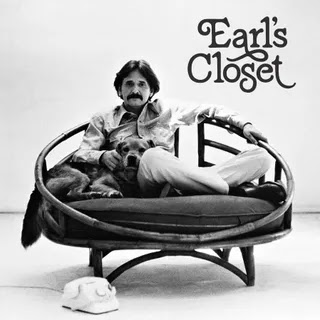

Hagan spent a year cataloging the closet, whittling down the tapes into Earl’s Closet: The Lost Archive of Earl McGrath, 1970-1980, a Light in the Attic compilation produced with the assistance of Pat Thomas. Don’t expect any Rolling Stones-related relics here. Earl’s Closet showcases 22 demos and home recordings McGrath collected over the course of the ’70s. Sometimes these recordings were demos sent directly to McGrath and sometimes he had a hand in their creation, but there’s no one thing tying together the music outside of his own tastes—tastes that reflected the era as much as they shaped it.

Earl’s Closet suggests McGrath gravitated toward country-rock made either by Hollywood cowboys or Texan weirdos while also finding sustenance in mellow folk-rock and distillations of ’60s pop. Other sounds crossed his radar, notably soul and a bit of harder rock’n’roll, but sun-bleached troubadours provide the spine of Earl’s Closet, while Daryl Hall and John Oates serve as its fulcrum. McGrath’s first and greatest discovery, Hall and Oates were swiftly poached by Ertegun for Atlantic, a label that would prove to be a creatively fruitful but commercially frustrating period for the duo. Veterans of Philadelphia’s soul scene—they rejected an offer to become house songwriters for Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff at Philadelphia International—they refashioned themselves as folkies and couldn’t resist threading artier elements of rock and pop, as evidenced by “Baby Come Closer” and “Dry in the Sun,” two Hall originals that are surprisingly funky even when they’re rooted in folk.

Such casual blurring of genres suggests the journey charted on Earl’s Closet. The first part of the voyage centers on California, with Delbert McClinton and Terry Allen both writing tales of how they moved from Texas to California (“Two More Bottles of Wine” and “Gonna California,” respectively). McGrath signed McClinton and his partner Glen Clark to Clean, where they’d issue two albums as Delbert & Glen, while Allen never quite managed to break into the big leagues. Allen eventually carved out a niche as a Southern-fried outsider artist—his 1979 double album Lubbock (on everything) is an Americana classic and he’d collaborate with David Byrne on 1986’s Sounds From True Stories—but not everybody went onto such success. Hagan couldn’t identify three of the artists here—the bittersweet winds of “Only Yourself to Lose” is credited to the absurd moniker Kazoo Singers—while many other acts operated on the margins of the mainstream: ’60s veterans struggling to find their way forward in a new decade. Andy Warhol associate Ultra Violet fades into the dawn on the languid “How Do You Do (Children of the Most High),” old folkie Paul Potash takes stock of the hippie hangover on “Holy Commotion,” and there is space for not one but two members of Detroit rebels the Amboy Dukes, a band that also counted Ted Nugent as a member: Dave Gilbert is in Shadow, who deliver the sugary pop rush of “Oh La La,” while Johnny Angel sounds like an endearingly cut-rate Rod Stewart on “Invisible Lady.”

Naturally, there are some sons of Hollywood in Earl’s Closet as well. Michael McCarty, the stepson of the notorious B-movie director Ed Wood, is represented by “Christopher,” a piece of dense, crystallized power-pop reminiscent of early Emitt Rhodes. (Fittingly, McCarty spent some time in the L.A. pop band the Palace Guard after Rhodes departed the group.) Mark Rodney, son of Red Rodney—a jazz trumpeter in Charlie Parker’s quintet between 1949 and 1951—is here with “California,” whose smooth groove is much funkier than the records the singer/songwriter cut with John Batdorf in the early ’70s. Batdorf & Rodney were kindred spirits with artists like Country, the first band McGrath signed to Clean, in that they were heavily influenced by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young; “Killer,” the contribution from Country here, distills the essence of CSNY in a way that recalls America’s “A Horse With No Name.”

All these mellow vibes mean that the final stretch of Earl’s Closet—the five songs that comprise Side D in its double-LP incarnation—sounds particularly bracing. David Johansen works out an early, ragged version of “Funky But Chic,” Detroit soul belter Norma Jean Bell tears through “Just Look-ah What You’ll Be Missing” and the Jim Carroll Band is a coiled nerve on “Tension,” a song he’d later turn into “Voices” for the soundtrack for the 1985 James Spader film Tuff Turf. All three tunes capture the late-’70s NYC renaissance, a happening that extended from punk clubs to the dance floor, and they also function as the closing chapter for McGrath's time as a record man. He wasn’t alienated from the new wave—he would remain close with Carroll over the years—but he was a man who got bored easily: The music industry followed a spell in the film business. (He maintained that he was the one who created The Monkees, only to have his agent steal it from him.) He had other adventures to pursue, so he left behind his time as a record man in his closet, waiting to be excavated by future generations who would marvel at how vividly these unheard documents capture the sound and spirit of their time.

0 comments:

Post a Comment