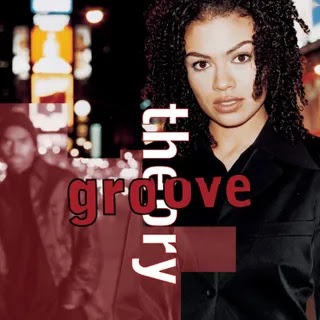

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the duo’s first and only album, a cool and atmospheric bomb thrown into the waters of ’90s R&B.

Bryce Wilson founded Groove Theory to resuscitate his creative drive. The Queens native had joined the hip-house group Mantronix as a teenager in the late ’80s to chase rap dreams, but the group’s dense, racing production left little room for the battle rapping and beatboxing he grew up on. A few years later, burned out after touring and recording two albums, Wilson quit the group. “I didn’t want to do dance,” he later told the music weekly Echoes. He did still want to make music, though, so he embraced producing, hoping it would take him where Mantronix hadn’t.

Wilson bought equipment and started messing around. He had no clue what he was doing, so he’d listen to records by soul maven Donny Hathaway and new jack swing architect Teddy Riley and reconstruct them. For a year, he fiddled around in his home studio, refining his beat-making bit by bit. He eventually became skilled enough to land a publishing deal, and Groove Theory soon followed, its name intended to invoke body and mind, impulse and intention.

The group’s eventual 1995 debut touched down during an R&B explosion years in the making. Mariah Carey, Toni Braxton, and Whitney Houston topped the charts with soaring, melismatic ballads. Yearning boy bands like Boyz II Men and Soul for Real sang wistfully of bended knees and candy-coated raindrops, while teen dynamos Brandy and Monica crooned about crushes and shit days. TLC crept; Jodeci feened and freeked; D’Angelo and Mary J. Blige repurposed ’70s soul for smoky fusionism and slick blues. The genre was so ascendant that even pop provocateur Madonna drew from its waters, roping in super producers Babyface, Dallas Austin, and Dave Hall for her uncharacteristically earnest sixth album.

Groove Theory peered into this vast, teeming ocean and shrugged. United in contrarianism, Wilson and eventual bandmate Amel Larrieux defined themselves against the dominant sounds of the day and set about toning down spectacle and emphasizing atmosphere. Their first and only album together, a moody, downtempo R&B record, posited Quiet Storm, a radio format that celebrated generations of Black music but was often hostile to rap attitudes and sounds, as R&B’s next frontier. Imagine Belly’s iconic title sequence—goons snaking through a throng of clubgoers, warm blue light encased in darkness, the icy melodies of Soul II Soul’s Caron Wheeler—and then escort all the occupants outside. That resulting husk of space is Groove Theory: vacated, lonely, but still communal, traces of others lingering in the air. By the end of the decade, the pair would split, Larrieux diving into jazz and soul, and Wilson producing for bigger acts like Toni Braxton and Mary J. Blige. But in the few years they were together, Groove Theory quietly resisted the rising tide.

Before Wilson met Larrieux, the groove was truly theoretical. As Wilson recruited singers for Groove Theory, even one from Mantronix, no one seemed to understand his spare, chilled-out production—especially his publisher, Rondor Music, who wanted him to make tracks that featured the explosive, adrenal rhythms of new jack swing. He found a kindred spirit in Larrieux, a songwriter, and assistant to Karen Durant, the music exec who signed Wilson. At 19, she already had a well-developed artistic identity after attending Philadelphia’s High School for Creative and Performing Arts and growing up in the West Village’s famed and eclectic Westbeth building, a rent-controlled apartment complex for artists. A lover of poetry, jazz, and Sade Adu with a subdued, sensual style, Larrieux clashed with producers who wanted her to be loud and sexy.

Wilson was different. At the recommendation of Durant, Larrieux wrote lyrics to one of Wilson’s beats and then went to his home studio to record a demo. They recorded it in his tiny bathroom, and Wilson was so mesmerized by their chemistry that he invited her into the group. She seemed to share his commitment to drawing outside the lines. “Her melodies and her notes were just like coming from a totally different angle,” he explained.

Larrieux accepted, and subsequent bathroom sessions produced the single “Tell Me,” their forthcoming hit and most canonized song. Built around a supple bassline, slick percussion, and soft keys, “Tell Me” blurs admission and confrontation. “I’ve been doing my own thing/Love has always had a way of having bad timing,” Larrieux sings, winding up for a question that’s actually a command. The track’s throbbing rhythms and cool mood embodied Wilson’s vision for the group, R&B as body high and head-trip.

Larrieux and Wilson had no attachment to the song though, because Larrieux had originally written the lyrics for another singer. Pawning off “Tell Me” to British group Rhythm N Bass, they left it behind as they recorded Groove Theory, returning to it at the butt end of the process just to pad out the album—and not at all expecting it to be a hit. In their view, “Tell Me” was too easy to make, “so straight up I’m embarrassed,” Larrieux said as their official version charted. It also wasn’t innovative enough.

Wilson hoped to, in his words, “kill new jack swing,” a goal borne out of his battle rap-bred competitive spirit and his frustration with music execs asking him to copy his muse Teddy Riley. And Larrieux wanted to dethrone sex as the default language and image of love. In a 1995 interview, she said, “I’m trying to make the impression on young women that you don’t have to be this sexy goddess—just have a love for music.” Groove Theory’s second single, “Keep Tryin’,” subtly broadcasts their anti-pop creed. “Your day is coming though it seems far/Things will be clear when you love who you are,” Larrieux sings with sweet conviction.

Groove Theory did avoid overt sexuality, but the omission was more a product of contrarianism than prudishness. “We have no desire to make ‘fast food music’ or sound like everyone else on the radio,” said Wilson in 1995. That deviant ethos drove them to seek themes other than heartbreak, desire, and romance. Although there’s plenty of all three on Groove Theory, songs like “Baby Luv,” a sweet ode to Larrieux’s daughter, and “Time Flies,” a track about the whiplash of growing up, explore passion without eros.

That divergent impulse extended to their influences, which ranged from soul and R&B classics to their contemporaries. Their lush cover of Todd Rundgren's “Hello It’s Me” is indebted to the Isley Brothers’ classic take on the song, radiating both longing and melancholy. The track doesn’t feel like a throwback though; compared to the Isley version, Groove Theory’s drums are snappier, the bassline meatier. And Wilson’s jazz-inflected production on “Time Flies” and “You’re Not the 1,” which was originally written for Mary J. Blige, channel the slick-but-street beats of Q-Tip and DJ Premier. Groove Theory detested the radio, but they loved Black music.

One significant difference between Wilson’s beats and those of rap producers is a complete rejection of samples. Although the rhythm elements on “Tell Me” sound eerily similar to the ’80s classic “All Night Long” by the Mary Jane Girls, the song, like every other track on Groove Theory, blends programmed beats and live instrumentation. Session musicians, especially producer Darryl Brown, who Larrieux dubs the third member of the group in the liner notes, are heard across the album. Brown’s bass and guitar touches on “Come Home” offset Wilson’s thundering drum programming, underscoring the hope in Larrieux’s downcast writing. “The street will never love you like I do/So leave that life behind and come home/Come home/Baby, come home,” she pleads.

Brown’s deft hands also guide “Ride” and “Hey U,” Groove Theory’s takes on G-funk. Larrieux’s coyness short-circuits the former. When she sings she wants to go for a ride with a lover, she truly means getting into an automobile and turning a key. There’s no adventure, escape, or innuendo to the statement, a far cry from Adina Howard unsubtly beckoning “Do you wanna ride?” or Dr. Dre rolling in the four with 16 switches. The slow-burning “Hey U” fares better at funking out, Larrieux’s aching melodies and breathy harmonies wafting over Wilson and Brown’s sauntering, hydraulic beat. “All that’s left to say is hey you/Hey you,” she coos, stretching the embarrassment of seeing a rejected ex in public into graceful resignation.

Although Groove Theory’s fusions never feel as audacious as the worldbuilding taking place on other syncretic mid-’90s R&B albums like Meshell Ndegeocello’s Plantation Lullabies, Sade’s Love Deluxe, D’Angelo’s Brown Sugar, and Janet Jackson’s janet., there’s no friction from all the blending. Groove Theory imagined R&B as a tentpole genre that could house jazz scats, funk grooves, and rap edge without conflict. It’s no accident that the terms most often used to describe the group are “cool” and “smooth.”

That lack of tension turns out to be a feature as much as a bug. Larrieux sometimes seems so intent on avoiding histrionics and melodrama that she undersells her most impassioned writing. “10 Minute High” and “Boy at the Window” center on a teenage girl addicted to a drug and a boy who idolizes a womanizing, absentee father, but the characters are so tragic that they don’t feel real. And Larrieux’s restrained vocals drain the songs of urgency. She clearly had Sade songs like “Tar Baby” and “Maureen” on her mind (and probably some Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye cuts, too), but she hadn’t yet learned to wield melancholy and darkness rather than just evoke them.

Groove Theory’s arch R&B didn’t take hold among listeners or their peers. “Tell Me” went gold, as did the album, but most modern mentions of the group are soaked in nostalgia, the music invoked as a portal to adolescence and young adulthood. “‘Tell me’ IMMEDIATELY takes you back to the 90s,” writer Panama Jackson wrote for The Root in 2018, a typical paean. The group’s musical legacy is also scant. “Tell Me” has been sampled by Sadat X, G-Unit, and Wale, and Solange, Hikaru Utada, and Kelela have cited Larrieux as an influence, but Groove Theory ended up being a marginal record in a decade where all strains of R&B reigned supreme. A faint line can be drawn from Groove Theory’s hushed sensuality and hard beats to Little Dragon, the xx, and R&B duos like Denitia and Sene and Lion Babe, but it would be imposed rather than traced.

That small footprint is in part a product of the group essentially breaking up when Larrieux left over creative differences and launched her idiosyncratic solo career. Wilson later recorded a second Groove Theory album with singer Makeda Davis that reimagined the group as radio-friendly, but that refurb—which was shelved and later leaked—only underscores the charms of the original lineup. That sequence of events and occasional reunion concerts have prompted interviewers to regularly ask Larrieux and Wilson about the possibility of a true Groove Theory sequel, a question both artists have answered enthusiastically. But it’s probably more fitting that an album designed to bypass radio and commerce lives on in memories, unmoored from the music industry and canons but appended to bodies that, during some distant commute or club night or first kiss, felt, and still feel, the groove.

0 comments:

Post a Comment