Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit a hard-rock colossus, one of the heaviest and bleakest albums to come out of the early ’90s Seattle scene.

A few weeks after the notorious 1985 Parents Music Resource Center hearings, where the so-called “porn rock” lyrics of musicians like W.A.S.P., Prince, and Cyndi Lauper were debated before a Senate committee, the Seattle talk show “Town Meeting” devoted an episode to the issue of “obscene” pop lyrics. At one point, the host gave the floor to an 18-year-old audience member named Layne Staley, who at the time was fronting a local glam-metal band called Sleze, and offered a personal take on the manufactured controversy. “Our lyrics are all positive—we don’t use bad language or sing about drugs and sex,” he said, “but I just want the freedom to write about what I want.” Wearing blue-tinted aviators with his hair teased several inches above his head—the glam-metal look of the moment—Staley wasn’t nearly as high-profile as Twisted Sister’s Dee Snider, but his brief take echoed Snider’s PMRC testimony. They were both participating in a heated cultural moment when it felt like pop music was under direct threat of censorship by an ascendant cadre of cultural conservatives.

Five years and a handful of band changes later, Staley’s first hit single with Alice in Chains stuck to that topic. The lyrics to “Man in the Box” came to Staley after dining with some vegetarian Columbia Records executives who explained how veal was derived from calves raised in tiny enclosures. “So I went home and wrote about government censorship and eating meat as seen through the eyes of a doomed calf,” Staley explained. The explosive chorus may have been the most attention-grabbing part of the song, but that core riff was a novel moment in hard rock–Staley’s acidic yawp doubling guitarist Jerry Cantrell’s serpentine melody to conjure the pained moan of a beaten creature.

There was nothing quite like “Man in the Box” on the radio or MTV at the time. Director Paul Rachman set the song’s video at an abandoned farmhouse and shot it with a low-budget art-horror vibe that distinguished it from its Headbangers Ball contemporaries. Though Cantrell looked very much the metal guitarist—long straight hair, shirtless under a leather jacket—Staley’s ratty blond dreads, goatee, and sad-eyed gaze didn’t fit neatly into any genre. It was eye- and-ear-catching enough for MTV to grant the video its prized “Buzz Bin” designation, concocted a few years earlier to grant “next big thing” status to lesser-known or genre-agnostic artists. By mid-1991, Alice in Chains weren’t just a promising new metal band, but had been programmed into the nascent “alternative” landscape populated by fellow Buzz-worthy acts like EMF, Jesus Jones, and P.M. Dawn.

It's become a standard part of the grunge origin story that “Man in the Box” was the first national hit to come from the region that would soon re-define American music and popular culture in its own image. While Seattle-area bands Screaming Trees, Mother Love Bone, and Soundgarden had already garnered national interest, Alice in Chains were the first Buzz Bin band to sport flannel on MTV, introducing the world to the guttural grunge yowl that Kurt Cobain and Eddie Vedder would soon come to personify. At the same time, Alice in Chains never really thought of themselves as a “Seattle band,” however ill-defined that term was, and their first national tours for their debut LP, Facelift, predictably came on some ill-fitting bills. They weren’t nearly metal enough for the fans of godheads Megadeth, Slayer, and Anthrax, who threw all manner of shit at the band during their opening set; they weren’t pop enough for Van Halen fans, whom Staley constantly trolled during Alice’s opening slot on the For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge tour.

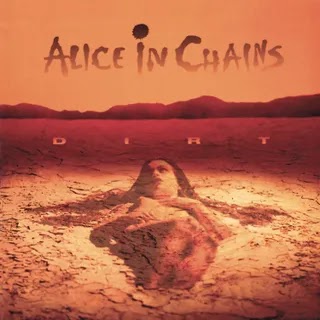

On 1992’s Dirt, such distinctions failed to matter much anymore. The band merged Seattle scuzz, the vestiges of pop-metal, and Staley’s limitless self-loathing into a hard-rock colossus. The title itself says it all: Dirt is, on one hand, the most elemental album of the grunge era, tackling the big questions with bluesy and Biblical seriousness: a busted dam, a rainstorm, a flood, a big old pile of them bones. For dirt thou art, And unto dirt shalt thou return. It’s also an album about feeling like dirt, and knowing that others see you that way. Dirt is by and for a dispossessed generation who came of age in the shadow of Vietnam, amid skyrocketing divorce rates, hard drugs, and an ever-widening gap between the haves and have-nots. All this time, they swore they’d never be like their old man. “There’s a growing group of people in the States that just don’t feel a part of stuff,” Cantrell said in 1993. “They feel outside, they don't want in on the Dream. They want out, man, out. And our music is a very small part of that.”

Staley puts it more bluntly on “Junkhead”: “But we are an elite race of our own/The stoners, junkies and freaks.” And with Dirt, a collection of grimy bummer jams, pungent riffs, glowering shock rock, and a handful of hard rock’s most enduring ballads, he gave them their scripture. The album rightfully made Alice in Chains one of the most famous bands in the world, and revealed them as one of the most gifted, capable of shifting from the B movie jump-scare screams of “Them Bones” to the poignant hesher existentialism of “I’d like to fly/But my wings have been so denied,” from “Down in a Hole.” It’s not for the faint of heart, either: Dirt is one of the most unremittingly bleak albums ever released by a major label. As they toured it through arenas and amphitheaters, tens of millions of fans were listening—and screaming along—to Staley plumbing the depths and torment of his heroin addiction.

A painfully fragile rock frontman if there ever were one, Staley was crushed by the death of Mother Love Bone singer Andrew Wood from a heroin overdose. Chris Cornell recalled to grunge historian Mark Yarm that Staley made a heartbreakingly dramatic entry at Wood’s wake: “Layne flew in, completely breaking down and crying so deeply that he looked truly frightened and lost.” A year or so later, in the klieg lights of post-“Box” stardom, Staley started using. “One of my ways of dealing with the success was to get really high,” he told a reporter. “I didn’t know how to deal with it. I’ve never been really good with people and crowds—going out and meeting a hundred people and shaking hands makes me nervous. So I started fuckin’ around with heavier things.”

While Cornell paired with Wood’s erstwhile bandmates to pour his grief into the Temple of the Dog ballad “Say Hello 2 Heaven,” Alice in Chains took a different tack on their own homage. Director Cameron Crowe was directing the Seattle-set film Singles at the time, and he sent the band into the studio to record a soundtrack cut. Along with jamming out some acoustic songs that would be packaged together on the Sap EP, they recorded “Would?”, which sounded like Jane’s Addiction’s shamanistic psych-rock soundtracking a biker rally, and would become the best track on the soundtrack. Over a slithery, dark-glam groove from bassist Mike Starr and drummer Sean Kinney, Cantrell’s enigmatic and suggestive incantations set up Staley to explode on the chorus. Far from an encomium for his lost friend, Staley, himself in the throes of addiction, screams the song to its conclusion with what amounts to a tantalizing, terrifying warning: If he succumbed to the temptations of heroin addiction, could you?

In the early 1990s, a lot of people were doing just that. Heroin was more potent than ever—by one measure, its purity had jumped from 4% in the mid-1980s to 65% in the early 1990s, an increase that made the drug far more seductive to the curious. Seattle was hit especially hard, with heroin and morphine-related emergency room visits more than doubling between 1988 and 1994. Kurt Cobain famously struggled with addiction up to his death; Mark Lanegan nearly had an arm amputated because it was so infected; Stefanie Sargent of 7 Year Bitch died from an overdose the summer before Dirt came out. But in popular culture, heroin wasn’t treated as a public health crisis as much as a sardonic part of the local color. Current Sub Pop CEO Megan Jasper framed her first visit to the city in the late 1980s with appropriate irony: “Welcome to Seattle: mountain climbers and heroin addicts.” A November 1992 Times story claimed that grunge was “inspired and tempered by that city's three principal drugs: espresso, beer, and heroin.”

Heroin had been a dependable rock star muse and subcultural cautionary tale since Lou Reed chronicled its instantaneous and confusing euphoria on a song that quickly became a live favorite—and which Reed often accompanied with a performative demonstration of tying off and fixing. Yet despite a cultural canon of twentysomething icons dying from heroin overdoses—Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Sid Vicious, Darby Crash, Jean-Michel Basquiat—rock culture tended to mordantly focus on the survivors. Thus: the ubiquitous dad jokes about Keith Richards’ dauntless dependence, The Onion begging a past-its-prime Aerosmith to get back on the smack, and the late-life resurgence of the original “unredeemed drug addict” William Burroughs, who cameoed in Gus Van Sant’s 1989 heroin-themed film Drugstore Cowboy and recorded a one-off with Kurt Cobain a few days before Dirt hit stores. Most dismal was the irony-pilled early ’90s kickstarting the morbid “heroin chic” fashion trend, epitomized by Calvin Klein’s early-1990s “Obsession” campaign featuring ultra-thin, expressionless model Kate Moss.

After a failed trip to rehab at the same clinic where Andrew Wood stayed, Staley quit cold turkey to start work on what would become Dirt. Unlike contemporaneous bands who used the drug as a vehicle for tasteful remorse, painful autobiography, or wink-wink wordplay, Staley eschewed subtext or sarcasm in lieu of a frightening carnival ride straight into the terrifying depths of smack-induced panic and despair. Dirt’s most successful heroin songs illustrate the drug’s ghastly effects by dramatically fluctuating between sonic and emotional extremes. On “Sickman,” Staley’s maniacal verses are underpinned with a wild stereo-panned drum loop which—cued by a delirious Staley scream—spirals down into a depressive waltz-time dirge for the chorus: “Ah, what’s the difference, I’ll die/In this sick world of mine.” In concert, like Reed, Staley would jab his arm with the microphone while performing. On “God Smack,” Staley chews the scenery in full grunge-Nosferatu drag, and “Angry Chair” ping-pongs between murky dope-fiend paranoia and a breezy “I don’t mind, yeah” refrain that comes in out of nowhere, sounding like the brave public face of an otherwise miserable addict. “Hate to Feel” contains the most depressing couplet about the descent into addiction: “Used to be curious/Now the shit’s sustenance.”

Dirt is quite a tough hang, nowhere so much as the mid-album back-to-back paeans to pain. Staley is still buried in his own shit, and things seem to be getting worse. “Junkhead” is a simultaneous ode to heroin and a sneering dismissal of the normies who’ll never know the truth. The refrain—“What’s my drug of choice?/Well, what have you got?/I don’t go broke/And I do it a lot”—is frighteningly celebratory, delivered like a valedictory address from a newly minted 25-year-old rock star who’s reached the absolute apex of fame-fueled addiction. The title track follows like a depressive solo come-down in the hotel after the show, with Staley doubling Cantrell’s opium-den riffs with that same ghoulish moan. They concoct a disconsolate psychedelic requiem, like Sabbath in Prozac Nation. Even in the “I Hate Myself and I Want to Die” moment of hard-rock self-loathing, the second verse of “Dirt” is chilling: “I want you to scrape me from the walls/And go crazy/Like you’ve made me.”

The obvious precursors here are Ozzy Osbourne’s “Suicide Solution” and Judas Priest’s “Better By You, Better Than Me”—both of which led to unsuccessful lawsuits from grieving parents of children who died by suicide. But maybe a better comparison is the Geto Boys’ 1990 track “Mind of a Lunatic,” a hyper-detailed gore-fest of murder and mental illness that its own record label initially refused to distribute. Indeed, as Seattle joined Black Los Angeles as the music scene-spectacle du jour, “Junkhead” and “Dirt” sketched a white outlaw icon to join the “gangsta” in the public imagination. But where the Geto Boys and N.W.A. rooted their provocations in a radical, if occasionally contradictory racial politics, the desperate, vengeful addict of Dirt pushes his body and mind to the edge of the abyss mainly to scare the squares. When, on “Junkhead,” Staley—a 25-year-old heroin addict with the keys to the kingdom—pits his “elite race” of dirtbag freaks against the workaday sheep of mainstream America who would do better to tune in, turn on, and tie off, it felt an adolescent taunt, not a liberatory offer.

Dirt’s centerpiece is a much more mature work about surviving a different kind of hell on earth—the catastrophic, decade-plus slog that killed millions and created a generation of emotionally devastated heroin addicts. But “Rooster” provides a complicated response to the rest of the album, because unlike Staley’s characters, he ain’t gonna die. “Rooster” was the nickname of Cantrell’s estranged father Jerry Sr., who served multiple combat tours in Vietnam and, unable to reacclimate to civilian life, left his son with his grandmother and mother (who died within six months of each other when Cantrell was 21). “Rooster” is a masterpiece, featuring Staley’s most impassioned vocal, Cantrell’s best riffs, and the group’s best harmonies. Cantrell’s mordant counterpoint to Staley’s yearning growl on the chorus has not lost an ounce of its potency, and the pair’s wordless, cooing introduction achieves a soulful solemnity all but invisible from hard rock of the era.

Columbia pulled out all the stops for the video, hiring Mark Pellington—fresh from directing Pearl Jam’s “Jeremy”—to oversee a clip that merged documentary interviews with war spectacle. Inspired by Platoon, edited by the guy who cut JFK, and overseen by Oliver Stone’s military consultant, the “Rooster” video is a minor epic. One of the great hard-rock ballads, “Rooster” dramatically broadens the scope of Dirt and brings its themes into greater focus. It’s an album about hard drugs and depression, but it’s also about men trapped in terrifying conditions beyond their control and trying to negotiate their doom through sheer bravado, if not self-delusion—which, of course, are often one and the same. Cantrell has said that the song acted as a bridge to reconcile with his father after decades apart, and on an album that’s otherwise obsessed with misery, “Rooster” is the lone ray of light breaking through the tightly closed curtains.

In 1993, music journalist Ann Powers caught up with Alice in Chains on the Dirt tour and found a group wandering the wilderness. The show she attends is a mess—Staley and bassist Starr are wasted and miss their cues—and she sees a band on the verge of collapse. “They’re like the kids in Lord of the Flies, stranded in strange territory with no clear rules of conduct,” Powers observed. “They’re trying to survive, but they’re eating themselves alive.” Soon, the band would fire Starr for increasingly erratic behavior, before spending the year touring the world, including a co-headlining slot on the 1993 Lollapalooza tour. Exhausted, they quickly recorded Jar of Flies, which sounded more like Zeppelin III than Master of Reality; nonetheless, it became the first EP to debut at the top of the Billboard album chart. But Staley’s heroin addiction never disappeared for long, and the band was forced to drop out of an opening slot for Metallica the next year, as well as the Woodstock ’94 bill.

Apart from the band’s self-titled third LP—which also debuted at the top of the album chart in 1995—Staley’s last recordings were subdued affairs. He provided lead vocals on Above, the underrated, jazz-inflected LP from the Mad Season “supergroup,” and displayed his increasingly frail appearance on the band’s MTV Unplugged set the next year. The band decided not to tour for the self-titled album, and after their fourth show opening for Kiss in 1996, Staley was hospitalized for an overdose. Soon after, his longtime girlfriend died of complications from her own drug abuse. The band went on indefinite hiatus, and Staley disappeared.

While Dirt was solidifying itself as a modern rock standard, a crop of lesser Alice-influenced bands were rising up the charts, and “heroin chic” was falling out of fashion, Staley was wasting away in isolation. When he was found dead in his Seattle apartment in 2002, Staley’s body had been decomposing for two weeks. It made for a morbid, but superficial grace note in his numerous obituaries: This was the man, after all, who was known primarily for vividly documenting his addiction and depression on an album that sold four million copies a decade before.

But that’s also far too simple and cruel an explanation. When he was 18, Staley, like so many other aspiring rock stars, wanted the freedom to write about what he wanted, how he wanted. As his fame increased, and his addiction and isolation deepened, he started using his music to shock, but also to build a bridge into his world. In this light, “Would?” is a far more accurate depiction of Staley’s drive to draw others into his personal darkness. “Try to see it once my way,” he pleaded, both a provocative dare to the squeamish and an invitation to keep him company, for as long as you could.

%20Music%20Album%20Reviews.webp)

0 comments:

Post a Comment