This suite of three intricate, hour-long guitar drones from the Swiss experimental musician suggests no ends or beginnings, just an unfathomable expanse of immersive sound.

A jumble of 825 motorized cardboard boxes, bumping into one another until they conjure the rhythm of distant techno. A sea of 663 suspended steel washers, bouncing from the floor until they invoke an overcrowded gamelan convention. A wall of 1,000 square feet of plastic wrap, blown by ventilators until it summons the pop and crackle of dusty vinyl. These are just three of the dozens of installations and sculptures that Swiss artist Zimoun has concocted over the past two decades, in order to elicit extraordinary sound from assemblages of everyday objects. (Highly recommended: Pass a few amused and mesmerized minutes or hours watching Zimoun’s other ingenious schemes.) They are attempts to create the feeling of chaos through control, to design systems so immense and intricate you are simply overwhelmed by their effect. When such sculptures work, they spark a keen sense of wonder—where else in your day-to-day existence have you overlooked such possibilities?

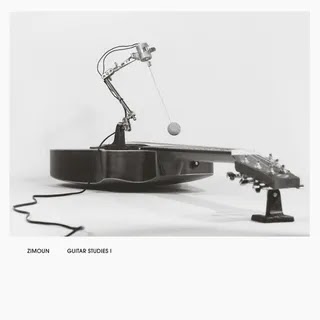

Zimoun’s actual albums, though, have never quite captured those twin senses of intrigue and imagination quite like Guitar Studies I–III, a new triptych of fastidiously made and totally immersive hour-long guitar drones that marks his debut for Lawrence English’s essential Room40. For each piece, Zimoun recorded a string of hour-long guitar improvisations, each exploring a different idea, like a motor vibrating the strings or a ball pinging against them. He played these takes through an assortment of amplifiers, sometimes hi-fi and sometimes shabby, and occasionally re-recorded the results by playing the passes back through carboard tubes or even half-broken speakers speckled with sand. There were no loops or shortcuts. An ostensible glutton for tedium, Zimoun stitched and mixed the layers together until they fit like tongue and groove.

If that all gets complicated, just remember this: By folding together so many layers, Zimoun created spans of electric sound that seem to have no end or beginning, no top or bottom. Listening feels like walking in some high desert that appears barren until you notice how alive everything is, including the soil itself. “It could even be endless,” Zimoun said of an earlier release. “It’s not going somewhere and not coming from anywhere—even if it is continuously changing.” At last, he masters that phenomenon.

The first of these three massive pieces unspools like a relatively quiet soliloquy from a member of Sunn O))). Massive chords roar in seemingly ceaseless waves, buttressed by low harmonies and static quakes that rise and fall, like breathing. The closer and longer you listen, though, the more you may hear; buried in the background of the track’s second half, for instance, there’s a piercing hum. Hearing that high tone glacially peel away from the surrounding lows is a subtle but visceral thrill, like time-lapse video of seasonal ice breakup.

The 64-minute finale moves like one of Rhys Chatham or Glenn Branca’s signature guitar armies, distilled until only the absolute essence remains. A fluorescent guitar tone serves as the piece’s through line, while other guitars offer variations—a distant tremolo murmur, a shorting cable’s crackle, a sweetly sighing riff. Just as there’s no clear beginning or end, “III” suggests that Zimoun doesn’t intend for this music to be happy or sad, glowing or gloomy; as with reality, it hangs always somewhere in between.

This liminal sense permeates “II,” the album’s centerpiece and masterpiece, plus its best balancing act between control and chaos. A murmur of a melody repeats from start to finish, like a spring daydream beset by static blips and ghostly hums. Think GAS marooned in the Black Forest, or Fennesz forever scoring the same square inch of shimmering ocean. The piece feels one note away from collapse or completion, as if one more element would either end it or elevate it into euphoria. But that change never comes, so “II” just flickers like an eternal flame, beautiful and bright but somber.

Guitar Studies I–III is bound to court one of the most rote criticisms of experimental music: Anyone can do this, right? Actually, maybe! Zimoun has been a guitarist since he was 10, but there are no fanciful licks or ornate riffs here, just patience and imagination. Given enough time and pedals, most decently competent instrumentalists could approximate most of these sounds, even if they lacked the wherewithal to build such intricate layer cakes. In that way, this music reflects geologic deep time, where rather ordinary events repeated over millions of years have shaped a splendid planet of mountains and canyons, rivers and plains. No one moment makes history or even stuns you; taken as a whole, the effect is completely awe-inspiring.

0 comments:

Post a Comment