Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the Cure’s commercial peak in 1992, a pivotal, fantastic, and often overlooked album in the band’s catalog.

Wish is what happens when a daring, visionary rock band starts slowing down; when the album-a-year pace and artistic reinventions pause to let the world catch up; when they reach a peak in popularity but start losing steam as a creative unit in the studio. While touring the album in 1992, the Cure played sold-out stadiums around the world, sounding stronger than ever, and most of the band quit afterward. They found an enduring hit with “Friday I’m in Love,” and a good portion of their fanbase felt slightly queasy about it. They were selling records and charting like never before, and critics began turning their attention to hipper, younger acts.

Granted, plenty of those bands were citing the Cure as an inspiration. From shoegaze to Britpop, alt-rock to post-rock, many of the prominent strains of music in the ’90s pulled from some corner of the Cure’s vast catalog, whether it was the tightly crafted post-punk of 1979’s Three Imaginary Boys or the ghostly sketches of 1981’s Faith, the devilish art-pop of 1985’s The Head on the Door or the immersive world-building of 1989’s Disintegration. Any one song from these records has enough character, vision, and atmosphere to spawn the careers of five entirely new bands.

On Wish, the Cure were beginning to assume the role of a legacy band—more important for what they had done than what they were currently doing—but they still had plenty of peers. Like R.E.M. on Monster, they cranked up the guitars to fit in with the current crop of radio rock; like Depeche Mode on Songs of Faith and Devotion, they ditched some of their signature synths in pursuit of a raw, live-band sound, complete with feedback and amplifier noise; like U2 on Achtung Baby, they took pleasure in challenging expectations, which meant balancing their totems of depression with gestures toward unfettered joy. In “Doing the Unstuck,” Robert Smith closes each verse with an uncharacteristic instruction: “Let’s get happy!”

Unlike those records, Wish is not remembered as a left turn or experiment, neither the start of a bold new phase nor an unsung dark-horse favorite. Instead, Wish is a solid record that sometimes gets overlooked due to the remarkable records preceding it and the largely disappointing work that followed. This humble reputation was aided by the music’s organic, communal genesis: It arrived in a rare moment of peace. Compared to previous career highs, the sessions were smooth and productive, even idyllic. With longtime producer David M. Allen, the quintet recorded in the stately Manor Studio in the English countryside, where they lived together and plastered the walls with cartoons and poetry.

As the sessions proceeded, there were no rumors that this would be the Cure’s final album, no dangerous drug use or health scares, no interpersonal conflicts to seep into the lyrics. Smith, who had gotten married to his high school sweetheart Mary Poole just a few years earlier, turned 33 on the day Wish was released, April 21, 1992. In the preceding months, the most scandalous news story to emerge in the UK tabloids was that Smith—whose severe employment of backcombing and Aqua Net had recently inspired the film Edward Scissorhands—had actually gotten a haircut.

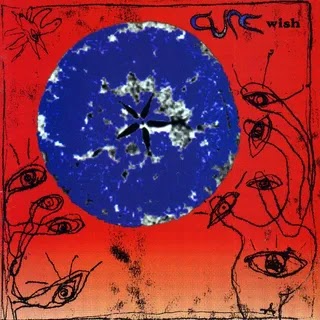

If there is a quality that distinguishes Wish from the rest of their catalog, it’s the dense, buzzing sound—the work of five people in a studio, as opposed to one person’s vision brought painfully to life. An immediate side effect was a creative process that tended to drift all over the place. First, it was going to be a pair of albums: one titled Higher and an atmospheric companion called Music for Dreams. Then it was going to be called Swell. On the cover, you will find a prominent drawing meant to depict a song called “The Big Hand,” an early favorite during the sessions that was cut from the tracklist. These might seem like minor footnotes, but for a band whose leader conceived his work with a monomaniacal focus, they represented a proud embrace of directionlessness.

While it scattered the vision for the record, the full-band approach led to some fantastic performances. Bassist Simon Gallup is irreplaceable, adding latent hooks to even the most abstract moments, a melodic undercurrent that connects singles like “High” to gothy throwbacks like “Trust.” Drummer Boris Williams performs with arena energy, making their ongoing ascent feel inevitable. Weaving between the rhythm section, you can hear guitarists Pearl Thompson—whose electric, mythical leads would soon result in a gig accompanying Jimmy Page and Robert Plant—and Perry Bamonte, a one-time roadie who added a burst of levity to their dynamic. There are records by the Cure that feel like full-body experiences—music that asks you to step inside in order to fully enjoy—but Wish glides, floats, goes with the flow.

It’s not like Smith lost his edge—and to prove it, he paraphrases Sylvia Plath in the very first song. But listen closely, and note what is bringing him down. “Open” seems to be narrated by the saddest attendee of some industry party, the kind of grim, obligatory event that requires massive amounts of alcohol to get through the night: “The hands all on my shoulders don’t have names/And they won’t go away,” Smith sings to Williams’ pounding drums, antagonized by dull conversations and fake smiles. These are not the laments of a hopeless young romantic, grasping for love and meaning in a loveless, meaningless world, but rather the private anxieties of someone who lived long enough to see his dreams come true—and realized they didn’t solve anything.

Smith finds a contrasting setting in the closing “End,” which seems to address the conflicted thoughts of a beloved artist performing to his audience: “I think I’ve reached that point/Where giving up and going on/Are both the same dead end to me/Are both the same old song.” To make matters even clearer, the chorus goes as follows, repeated over and over again like a tantrum: “Please stop loving me/I am none of these things.” In interviews, he described these words—the first he wrote for the record—as a message to himself, a reminder not to fall into the trappings of ego and delusion: “It might seem like it’s quite late in the day for it to all go to my head, since we’ve been going so long,” he explained with typical self-deprecation, “but the success has reached the kind of magnitude where it’s insistent and insidious.”

I imagine most people who play dark, artsy music for long enough will notice a particular show when the audience seems different—a little bigger, maybe a little more distant, maybe no longer wearing entirely black. Smith always took pleasure in writing pop songs as a kind of gateway—“That was always our intention,” he said, “to draw people in and then smother them”—and often, his romantic songs like “Just Like Heaven” and “Lovesong” helped set the stakes for the gloomier material around them. In the lyrics of “Friday I’m in Love,” the Cure’s giddiest single, he condenses this idea to an existential quandary: Can just one day of bliss justify all the surrounding pain and monotony? The chorus offers an answer, and the classic, chiming chord progression does not contradict.

Like a lot of great bands, the Cure have followed a parabolic journey, starting as a cult act, then peaking in the mainstream before settling back with their core audience. For many of those hardcore fans, Wish is a strong album whose deficiencies are diagnosable and treatable. If you’ve got a Cure head in your life, casually mention Wish to them and count the seconds until they bring up the outtakes. From the six excellent B-sides on 2004’s Join the Dots box set to the four instrumentals on 1993’s cassette-only Lost Wishes EP, these shadowy obscurities are enough to fuel decades of conversation regarding alternate tracklists for the true follow-up to Disintegration. (And not to mention, heightened expectations for the delayed installment in Smith’s meticulous, enlightening reissue series, where Wish has been the next item on the checklist for years.)

For new listeners, Wish may be an unrepresentative starting point but it does go down easy—even the filler tracks have a lightness that feels uniquely humanizing. “Wendy Time,” while not the Cure’s most memorable funk-rock excursion, still offers a whimsical adrenaline hit, as Smith’s opening meow snuffs out the fiery momentum of “From the Edge of the Deep Green Sea.” This is the precise type of tone shift the band would have difficulty replicating as the years wore on and their records took the form of jarring hodgepodges (1996’s Wild Mood Swings) and overcorrected moodpieces meant to reclaim the brooding melancholy of their signature sound (2000’s Bloodflowers).

Back when they settled on that sound in the early ’80s, the Cure could conjure vast feelings through sheer suggestion. Records like Seventeen Seconds and Faith have a sinister magic akin to those early, low-budget horror movies, full of distant murmurs and ominous shadows, jump-cut climaxes rendered in grayscale. Instead of showing you the monster, Smith realized our subconscious could fill in the blanks with something far scarier. With their increased notoriety, the Cure upped the ante on Disintegration and Wish to color in those details, swapping our primal fear of the dark for elaborate settings and scenery, real characters and dialogue. It’s why “A Letter to Elise,” with its strumming acoustic guitars and keys that sound like a broken xylophone, seems to embody an entire narrative arc in the music alone.

It could veer toward melodrama if the sadness didn’t seem so real, so inhabitable. On Disintegration, the Cure prolonged and accessorized the emotion, embellishing each instrument—the drums with heavy reverb, the bass soaked in chorus, the lead guitar solidifying while it played, like liquid into ice—until everything sounded how we feel at our lowest. It was a creative breakthrough and an emotional one: “The crux of this album is the horror of losing the ability to feel things really deeply as you get older,” Smith told OOR Magazine’s Martin Aston, pinpointing the driving tension of his songwriting. “It worries me and everyone that I know of my age.” There is a reason why so many of his lyrics turn to Christmastime and kittens and first loves—formative symbols that carry past adolescence, never losing their sentimental appeal.

In a sense, the Cure’s entire body of work can be heard as an inquiry into how childlike emotion fares against the crushing tedium of adulthood. “For me, the idea of growing up is this idiot idea, because I was more grown up when I was 13 than I am now,” Smith said in 2004. “To me, grownups [were] people that kind of sighed a lot and had worry lines and looked forward to the weekend. I don’t look forward to the weekend at all.” It’s a funny distinction, but it speaks to the particular escape that his best work provides: The Cure posit that any emotion—sadness, fear, nostalgia, unrequited longing, ill-fated optimism—is preferable to numbness

This is why, in the loudest and most desperate moment of Wish, Smith lashes out using these words: “You don’t feel anymore/You don’t care anymore.” Compared to Disintegration, these songs keep a foot in the adult world, where we are encouraged to appear a little more balanced. “The vulnerable, lost little boy side of my image is gradually disappearing, if it hasn’t gone already. But the emotional side of the group will never disappear,” Smith promised at the time, noticing his use of the word “man” in a lyric where he might have previously written “boy.” Eventually, on Bloodflowers, he would find a way to verbalize this dissonance: “She dreams him as a boy/And he loves her as a girl,” he sang on “The Loudest Sound,” a bleak song about an older couple vowing to live entirely through each other’s fading memories. It’s not exactly a happy ending, but then again, what did you expect?

The years that followed Wish brought some hard lessons: Thompson and Gallup quit temporarily. Williams left for good. Smith endured a long and brutal legal battle with his former bandmate, Lol Tolhurst, a co-founding member who had been fired at the end of the previous decade due to issues stemming from alcoholism. Wish’s distracted and labored follow-up, Wild Mood Swings, landed with a thud four years later, effectively ending the Cure’s tenure in the mainstream. In retrospect, Smith claims he saw the writing on the wall, and the commercial failure forced him to develop a more personal relationship to his art, blocking out the masses to please only himself and his devoted fanbase. You can hear him beginning to embrace this path on Wish, letting go of some perfectionism, accepting the inevitable. Everything ends; life goes on. It doesn’t make growing up sound particularly fun, or any more avoidable. But it assures us we don’t have to do it alone.

0 comments:

Post a Comment