Wendy Eisenberg’s trio combines bludgeoning post-hardcore with off-kilter runs, hairpin turns, and deceptively nonchalant vocals. The subject matter is serious, but it’s clear they’re having fun.

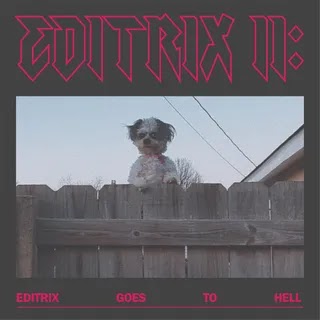

The first sounds emitted by Wendy Eisenberg’s guitar on Editrix’s second album are screeching arcs of noise. These parabolas of dissonance ricochet for over a minute before devolving into scattered jabs that twitch with anxious energy. Eisenberg revels in the friction of these kinds of uncomfortable tones, frequently pairing discordant harmonies with lyrics that hit in a similar way. Often they sing of the awkward, bitter feeling of being thrown into a world that twists us into shapes that feel unnatural—the cognitive dissonance of living in a society that insists you act in ways that are in opposition to your core values. But even as Eisenberg exploits the expressive potential of discord, they frame these personal and philosophical crises with a disarming mixture of sincerity and irony that is both funny and profound.

Eisenberg’s music takes several forms, including avant-garde jazz and tender folk-like songs they sing by themself, but the bludgenoning post-hardcore of Editrix is their bluntest, most provocative outlet for this discontent. The trio, which includes Steve Cameron on bass and Josh Daniel on drums, pounds its way through Editrix II: Editrix Goes to Hell’s 12 songs. Each band member bears down on their instrument, and they bolster the intensity with complexity of their interlocking riffs and rhythms, which are frequently disrupted by off-kilter runs and sharp left turns. Those tight hairpins, dextrous in ways that allude to Eisenberg’s extensive jazz training, foster a gripping unpredictability as the band cycles through multiple tempos and melodic passages. Spindly guitars get tangled around beats so heavy with syncopation they make 4/4 feel oddly metered, but Editrix playfully ride these unpredictable waves. It’s clear they’re having fun.

One of the consistent elements between Eisenberg’s solo work and Editrix is their ability to write sticky melodies that fit neatly into knotty chords and chromatic riffs that only occasionally resolve. They consistently find the square pegs that will miraculously fit a round hole, and their nonchalant, intimate style of singing makes the juxtaposition feel natural. Rarely do they shriek, growl, or moan the way a typical punk singer might, and they don’t strain their voice to be heard above the instrumental maelstrom. Instead they sing as they might if accompanied only by a single guitar, their voice perched high atop the mix so each lyric can be deciphered and absorbed.

Abrupt shifts in tone are typical of the album’s lyrics as well, which are peppered with tongue-in-cheek lines that swerve into more severe territory. “The anthropocene means humans are winning,” sings Eisenberg on “Queering Ska” before admitting dire acceptance—“I know that it will end/That it is ending.” When they sing, “It’s 2019, who is queering ska?” gleeful upstrokes seem to answer their own question, but in the next breath, whimsy gives way to the trauma of the following year: “It’s 2020, who is not on Earth?” On “Time Can’t Be Redeemed,” they find a witty way to express dark ruminations: “On the subject of whether or not to live, I’m undecided and can’t be swayed.” It’s not that they use humor as a coping mechanism, but that they understand the absurdity buried deep in the hellish conditions of life under capitalism. Rather than succumb to it, they laugh in its face.

At this point there’s nothing inherently radical about simply stating known truths: We live in a morally corrupt system that prioritizes profit and power over the lives and livelihoods of our neighbors and ourselves. We’re alienated and frustrated. What makes Editrix’s music feel truly radical and transformative is the playful, powerful way the music reflects the everyday paranoia of living during this crisis-laden moment. Like Fugazi before them, Editrix takes punk’s framework and stretches it to its breaking point, pushing listeners to question orthodoxy in all its forms—ethical, ontological, and musical.

%20Music%20Album%20Reviews.webp)

0 comments:

Post a Comment