The Virginia rapper’s latest is musically varied and vocally impressive, revealing an artist who continues to cut extraneous elements out of his songwriting and drill closer to the core of his style.

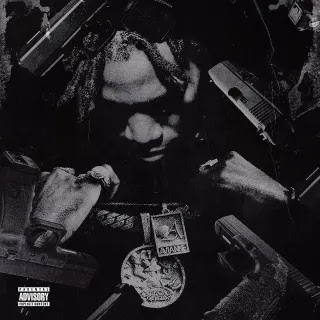

Pusha T’s voice—snarling and crystalline, among the most distinctive in his generation—would be compelling if he were rapping on a click track. But after the Clipse, the duo he had formed with his brother Malice, disbanded, the Virginia Beach rapper’s early solo efforts were marred by production that often suffocated him. Records like 2011’s Fear of God II: Let Us Pray and 2013’s Wrath of Caine can get lost in the digital-maximalist wilderness. Though he’d navigated similar lanes nimbly in the past, Pusha was now drowned out by beats that were crowded in the most predictable, post-Lex Luger ways, some of which he even let lure him into conspicuously borrowed flows. He eventually shed this to find something meaner and radically spare; his most recent album, 2018’s seven-song, 21-minute Daytona, mirrors this minimalism in its very construction.

The other thing, aside from leanness, that “Numbers on the Board,” “Nosetalgia,” and “Untouchable” have in common with Daytona is that none of them are produced by the Neptunes. After handling the vast majority of Clipse’s studio albums, Pharrell and Chad Hugo were all but absent from Pusha’s solo work. Now Pharrell returns to produce more than half of It’s Almost Dry, Pusha’s first new record in nearly four years. It’s a musically varied and vocally impressive effort from an artist who continues to cut extraneous elements out of his songwriting, drilling closer to the core of his style.

Clipse LPs were once conduits for the Neptunes’ most experimental rap beats; Pharrell’s work on It’s Almost Dry honors that legacy, leading Pusha into narcotized carnivals (“Call My Bluff”) and the climaxes of sci-fi thrillers (the naggingly eerie “Scrape It Off”). In fact, there’s a foreboding quality to all of the Pharrell beats here, from the opening suite of “Brambleton” and “Let the Smokers Shine the Coupes,” where the former’s electronic bounce and latter’s freneticism make each other seem more sinister.

The rest of It’s Almost Dry is helmed by Kanye West, along with a few co-producers, most notably the New York veteran 88-Keys on lead single “Diet Coke.” Kanye’s beats are not as uniformly excellent as Pharrell’s: Closer “I Pray for You” is dragged down by pedestrian drums, and “Diet Coke” plays like paint-by-numbers Pusha. (The latter song is perhaps a victim of the hyper-clear mixes the rapper prefers; it sounds like a slightly sterile version of the grimier songs it attempts to evoke.) But the best Kanye is enrapturing. On first listen, the slight, Colonel Bagshot-sampling “Just So You Remember” reminded me of the Daytona finale “Infrared.” It’s actually closer to being a Ka song, so quiet that it’s barely there. “Dreamin’ of the Past,” which is built around Donny Hathaway’s recording of John Lennon’s “Jealous Guy,” is the sort of song Kanye produced around the turn of the century: maddening at first for the obviousness of its sample flip, and then for its effectiveness. “Hear Me Clearly” sounds like the tail end of a nuclear winter.

The most thunderous beat from either producer is Pharrell’s “Neck & Wrist,” a lavalike midtempo track that would overwhelm most MCs. Instead, Pusha slips into lilting flows reminiscent of 50 Cent and G.O.O.D. Music signee Valee on the song’s verse and hook, respectively. On Daytona, he carried each song with robust performances that he played straight down the middle—often technically impressive, always appropriate for their songs. The beats on Dry simply require more finesse, leading to what’s far and away his most dextrous showing as a vocalist. Pusha feigns exhaustion on “Call My Bluff,” playfully syncopates the ends of bars on “Brambleton,” and maintains metronomic, even mathematical cadences on “Rock N Roll” and “Scrape It Off,” where not a syllable is out of place, but that precision does not come to dominate the songs.

A few months after Daytona’s release, Pusha flew to Berlin to speak at the Red Bull Music Academy. There, he leveled with a concert hall full of aspiring musicians: “If you want to talk about it, I really made variations of the same album for the past 20 years,” he said. “I know exactly who I’m talking to. I know exactly who my core is. I cater to that person. I don’t cater to anyone else.” On a writing level, this is largely true: Though Pusha has told some memorably unnerving anecdotes from his past, he is usually not writing full scenes—he arranges and rearranges shards of detail to create new iterations of familiar pulp. In other words, the currency of his style is execution, not experience.

All of which makes It’s Almost Dry’s opening song one of the most fascinating in Pusha’s catalog. “Brambleton” is an extended, mostly bemused response to Anthony “Geezy” Gonzalez, the former Clipse manager who served a eight-year sentence for running a $20 million drug ring in Virginia Beach, and who, in a 2020 VladTV interview, said that “95 percent” of Clipse’s rhymes were about his life. Inflammatory as Gonzalez’s interview was, Pusha’s rebuke of his claims is measured, even humble—“You would pay 16, I would pay 18” sounds more like forensic accounting than a blood feud—and wraps up tidily.

Pusha likes to lean on crime-movie tropes, but he invokes them with purpose. In some instances, this has the effect of making him seem extraordinarily unfazed by the world around him, as if the strongest response a life-and-death situation can trigger in him is a hazy memory of Carlito’s Way. But he is not willing or able to keep real life at bay forever. It’s Almost Dry’s second song, “Let the Smokers Shine the Coupes,” is also its least verbose, with few lines longer than six words. In its chorus, Pusha calls himself “cocaine’s Dr. Seuss,” which is about as far as one can go toward lowering the stakes of whatever is said next. And still, two things bleed into its opening verse. First Pusha returns, obliquely, to Gonzalez’s claims, which he seemed to have settled on the prior song. “If I never sold dope for you,” he raps, “then you’re 95 percent of who?” Later in the same verse is this line of thinking:

AMGs on auto cruise

The wrist singing’ Auto-Tune

The dope game destroyed my youth

Now Kim Jones Dior my suits

It’s easy to imagine Pusha placing the third of those four lines there to accentuate the thrill and sheer unlikelihood of his wealth. But it has the opposite effect, making the clothes and cars seem like meager consolation prizes for decades spent dodging arrest and assassination. Like Pusha’s other work, It’s Almost Dry stops short of explicitly considering whether what he did—and what he went through—in his early life is justified by the payoff. But lurking at the edges are some regrets that he cannot outrun.

0 comments:

Post a Comment