The British-Chinese musician trades the club tropes of previous albums for unadorned guitars and surreal soundscaping. It’s some of his most emotionally nuanced work yet.

Tim Zha makes music that feels like having a psalm read to you through the iridescent glow of your laptop screen. “Music is pretty inseparably tied to spirituality for me,” the British-Chinese producer told AQNB in 2017. Discussing the influence of his Christian upbringing, he described his music as being “concerned with understanding the experience of subjectivity, the experience of being bodied, which to me is always dominated and defined by the condition of being ‘fallen’ in a biblical sense.” Zha’s music as Organ Tapes always seems to be reaching for some form of redemption—a whispered prayer to be born anew, assembled from the scattered debris of another night at the club.

This idea of rebirth has been a constant in Zha’s music, with Organ Tapes’ sound continually mutating and evolving into new shapes over the years. On releases like Words Fall to Ground and Into One Name, Zha concocted a lo-fi hybrid of Afrobeat and deconstructed club so delicate it felt like it could shatter in your hands. On 2019’s slowcore-driven Hunger in Me Living, Zha incorporated more straightforward guitar and drum patterns while keeping his unique taste for sweetly synthetic flute and harp sounds. Uniting it all has been Zha’s transformation of club-filling pop tropes into the foundation for his intimate bedroom ruminations (as well as his densely Auto-Tuned voice, which mysteriously winds its way through his songs like a wounded serpent searching for sanctuary).

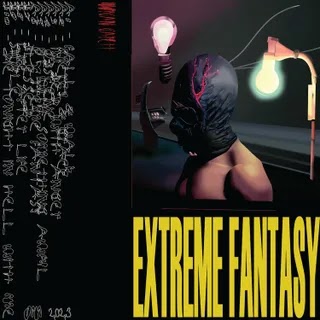

His new release for DJ Python’s Worldwide Unlimited label, Chang Zhe Na Wu Ren Wen Jin De Ge Yao (whose title roughly translates to “Sing the Song That No One Cares About”), represents yet another stylistic shift. Adopting a primarily acoustic approach, Zha becomes a kind of ghostly nomad, often abandoning drums entirely in favor of unadorned guitars and surreal soundscaping, ending up somewhere between Elliott Smith and Ecco2k. In some ways, the album mirrors the emo sensibilities that have overtaken the online musical landscape in the last few years. But where other young laptop artists like quinn or blackwinterwells might orient their songs around cathartic, earsplitting drops, Zha prefers to drift in a spectral quiet, emphasizing the tenderness of his fingerpicking and his uncannily disorienting samples. In its hushed sense of grace, Chang Zhe Na Wu Ren Wen Jin De Ge Yao represents some of Organ Tapes’ most emotionally nuanced work yet—a blurry, half-remembered vision from one of the unsung prodigies of the modern electronic underground.

As with all Organ Tapes releases, Zha’s vocals on Chang Zhe Na Wu Ren Wen Jin De Ge Yao are obfuscated by an almost impenetrable digital haze, each word phasing in and out like a thought on the very edge of becoming. His lyrics are often indecipherable, but occasionally you can make out brief silhouettes of meaning in the fog. On “Submission”—a brightly strummed acoustic chant that feels like it came from the same shimmering world as yeule’s “Don’t Be So Hard on Your Own Beauty”—Zha softly declares,“I was young, and I said I would change as I lived and I listened,” seemingly reflecting on his own growth. Only later does he modify the line into a repentant confession: “I was young, and I said I would change, and I did, and I didn’t.” Elsewhere, Zha lets his samples speak for him; “Eventually He Will Come Into My Life” pulls a quote from the 2014 film Rich Hill, a documentary chronicling rural Missouri teens trying to find hope in the face of abject poverty. “I praise God and I worship him, and I pray to him every night,” a boy’s voice quivers against a glimmering, cybernetic drone. “Nothing’s came, but that ain’t gonna stop me.” Zha casts this moment as a solemn epigraph for the entire record—a portrait of private, mundane faith, pleading for some intangible salvation.

Lyrical moments like these may act as dowsing rods for Zha’s thematic intentions, but one of his greatest strengths is how much he’s able to convey through sound and inflection alone. On “Never Had,” Zha builds a withered R&B lament around a distant guitar sample cloaked in crinkling distortion, cutting the instruments in and out as he layers his sighing falsetto harmonies one on top of the other. “Heaven Can Wait” is even more stunning: After a beautifully sparse opening verse consisting entirely of Zha’s fragile voice and guitar, an otherworldly sound collage washes over the song, suggesting an iPhone recording of a street performer spliced with the tactile rubbing of fabric, with idle chatter from passerby swirling all around. In Zha’s hands, this moment comes off like a triumphant solo, its melody distilled into a pure texture, as cold and artificial as it is warmly human.

Even on his strangest stylistic detours, Zha manages to infuse these melancholy songs with an aching longing for something greater. Whether it’s in the chintzy karaoke horns that adorn “Acid & Wine” like provincial fanfare or the Dirty Beaches-esqe rockabilly strut he adopts on “Earned,” Zha turns these small absurdities into new refractions of his weary worldview, where anything can be the basis for a wistful lullaby. It’s as if his songs are pleading to mend the fractures and dissonance happening within them, each one a diffuse portrait of contemporary music at its most mournful. As with all of Organ Tapes’ work, that might seem out of reach if it weren’t so openly and deeply felt.

0 comments:

Post a Comment