On his fifth album, Kendrick retreats from the limelight and turns to himself, highlighting his insecurities and beliefs. It’s ambitious, impressive, and a bit unwieldy.

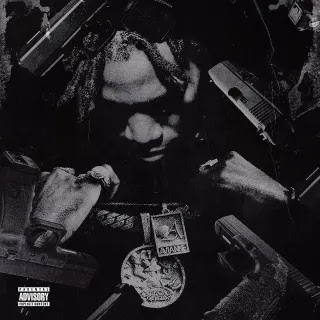

Kendrick Lamar is a giddy dramatist. He loves to pack his music with perspectives, personifying his many characters and muses with distinct voices, cadences, and beat switches that bring them to life. Those virtuosic tics have made him one of rap’s most celebrated storytellers and stylists; he is the first and only rapper to have won a Pulitzer Prize. For some, Kendrick’s elastic narration and indignant dispatches on Black life have made him a figure of supreme moral authority in hip-hop—a role he spurns on his fifth studio album. Kendrick spends Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers gleefully immolating his cherished reputation, swinging between caustic taunts and plaintive confessions over slick funk and soul production that gleams like shards of a mirror. The double album offers rap’s most jarring heel turn since Future cut loose on Monster, taking an unfocused but probing look at Kendrick’s most elusive character: himself.

Five years have passed since Kendrick released the punchy and vivid DAMN. and curated the easygoing soundtrack for Black Panther—eons in the rap world, and quite a chunk of regular time too. Aside from the splashy launch of pgLang, his opaque media company with Dave Free, and a few scattered features, Kendrick has kept a low profile. His final album for his longtime label home Top Dawg Entertainment enters a world shaped by the pandemic, #MeToo, and the global protests against police brutality, events Kendrick comments on across the record while recounting how he’s spent his hiatus. His main priority, however, is clarifying who, exactly, Kendrick Lamar represents.

The short answer is his family and his homies. The search for the longer answer propels the album. Prompted by narrator Whitney Alford, his romantic partner since high school, Kendrick opens the record by framing his honesty as dangerous, the first of many disclosures to come. “I been goin’ through somethin’/Be afraid,” he says, a warning that is followed by frantic double-time verses that slink around oblique piano stabs and brisk drums. His rapping jerks and lurches as he reveals he’s going to therapy and wracked by grief and shame, feelings that he copes with through luxury purchases and infidelity. Even as he details a specific fling, his storytelling frays, held together by the repetition of his paramour’s eye color rather than mise-en-scène or dense rhyme.

Throughout Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, Kendrick seems to actively reject the elegance and structure of past songs like “DUCKWORTH.” and “good kid,” writing in quick strokes and sketches that channel his messy admissions. Ideas scamper around like field rabbits and he avoids clean hooks, denying the listener easy access to his thoughts. It verges on antipop. His flows streak across “Count Me Out,” bouncing off the kick drum, dancing with the chords. The “Kim”-inspired “We Cry Together” stages a noxious melodrama where Kendrick and Zola star Taylour Paige trade barbs that feel almost improvised despite being tightly rhymed and metered. Eminem can finally retire happy.

His commitment to untidiness extends to the production, which is smooth but askew, rhythms and chords stacked precariously. Many of the songs, most of which have at minimum three producers, seem to split at the seams. On “Rich (Interlude),” Duval Timothy’s piano lines drift apart and glom back together, rain into vapor into clouds. On “Purple Hearts,” the drums fall away for the entirety of Ghostface’s stellar verse, strings and splashes of piano shadowing the rapper’s meter. The performances don’t always tap into the lushness of the production, but the beats and occasional R&B sample here and there give the often rambling verses some much-needed shape.

Kendrick meanders to the album’s high points, stopping for strange and goofy hot takes on cancel culture, a neuron-melting non-issue that explains literally no rich and famous person’s actual life. His candor turns pugilistic on “N95” and “Worldwide Steppers,” tracks that find him praising Oprah’s moxie (“Say what I want about you niggas, I’m like Oprah, dawg”) and lamenting a time he paid for unhealthy catering. “I am not for the faint of heart,” he says after a preamble by Kodak Black, whose inclusion here and throughout the album brings to mind DaBaby and Marilyn Manson’s appearances on Donda. It's unclear whether his presence is meant to make a case for redemption or musical kinship.

Kendrick’s verse, rapped in the tight pockets of a throbbing vamp, steamrolls into trolling lines that detail vengeful hookups with white women that might be described as Ice Cube’s “Cave Bitch” meets Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice. The bars aren’t particularly inflammatory in the context of the song, which casts Kendrick’s Becky cravings as one fiber in the global tapestry of imperfect people who deny and sidestep their flaws. But Kendrick clearly gets a kick out of needling the listener, a current that runs through the album. As his ribbing starts to feel empty—“Hello, crackers!” (“Savior”); “A celebrity do not mean integrity, you fool” (“Rich Spirit”)—the stated purpose of his venting grows shaky. Is his goal to be honest or impish? Does he want to bare his soul or his fangs?

On “Auntie Diaries,” the tale of two relatives whose experiences with gender shaped his accountability to family, he attempts the former but fumbles into the latter. In trying to impart a lesson about how he learned then unlearned to say the f-slur, he makes himself the main character in his queer relatives’ stories and he uses the slur wantonly. Few rap listeners will be new to the word and his intentions are clear, but aren’t there other stories he can tell about the trans people in his life? Kendrick has never been a perfect character actor, but in the past he at least imbued roles with some mark of individuality. Compared to JAY-Z’s “Smile,” which manages to tell the story of Hov’s mom coming out of the closet and mixes flexes and intimacy, “Auntie Diaries” lacks depth.

On the penultimate track, “Mother I Sober,” Kendrick finally responds at length to Whitney’s initial assignment. Dropping his voice to a teary murmur, he relates a bleak tale of domestic and familial violence that ensnared himself, cousins, and his mother. Instead of lurid details, the story pivots on stony silences that exile everyone to the confines of their minds, where they bottle up pain instead of processing it. “I wish I was somebody/Anybody but myself,” Portishead’s Beth Gibbons murmurs for the hook, her ghostly timbre capturing the dissociation the violence has wrought. The song ends with singer Sam Dew crooning, “I bare my soul and now we’re free,” a tidy conclusion that provokes more questions than it answers. But the song at least has a mission and a throughline, and Kendrick labors to probe his feelings and hangups, a sense of effort lacking elsewhere on the album.

Despite all its aggrieved poses and statements, the often astonishing rapping, the fastidious attention to detail, and its theme of self-affirmation, Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers ironically never settles on a portrait of Kendrick. Perhaps that slipperiness is the thrust of the album, which might be read as his answer to a question he asked a decade ago, before he was anointed as hip-hop’s conscience: “If I mentioned all my skeletons, would you jump in the seat?” That fear of being defined by trauma and shame resonates throughout, but Kendrick and his blemishes are so defined by negation—of white gazes, of Black Twitter, of weighty listener expectations—that by the time the record ends, Kendrick’s “me” is just as nebulous as the effigy he’s spent the album burning. Gods are born in vacuums.

0 comments:

Post a Comment