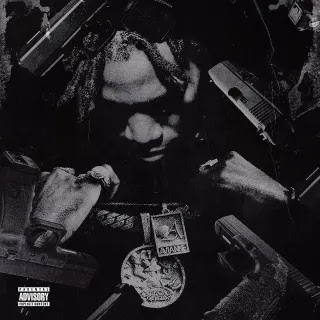

The companion piece to his 2021 self-titled record diverges from the innovation and technical proficiency in favor of introspection and contemplation. It is a richly detailed, deadpan elegy for his stolen youth.

Vince Staples has long sought to take the shine off gangster culture. Much like a military veteran can sniff out stolen valor, he can tell which rappers romanticizing life on the street are full of shit. None of this shit is fun; it’s stressful. You don’t sign up to see your friends get killed; you survive it, or you don’t. More than a few have painted Staples as a nihilist devoid of hope, but he’s closer to a hard-earned cynic, someone who’s seen too much to believe any empty platitudes.

Staples’ new album, Ramona Park Broke My Heart, is an elegy for his stolen youth—a subtle lament for the life he’s led that also pines for the one he never did. It shares the clarity he’s exhibited since the start of his career, a perspective aged by the streets he was raised on. There are no solutions here, no grand epiphany. His home just no longer provides the same comfort that it once did. A companion piece to his 2021 self-titled LP, Ramona Park Broke My Heart diverges from the innovation and technical proficiency of earlier records, in favor of introspection and contemplation.

If Vince Staples was muted by its grayscale palette, Ramona Park Broke My Heart is colored with vivid nostalgia for the sounds of his youth. “DJ Quik” flips the G-Funk spirit of the titular artist’s classic cut “Dollaz + Sense,” drowning a vintage drum machine in gauzy atmospherics; the bass line’s electronic twang on “Magic” draws from the sound of that era more directly. “East Point Prayer” is the lone departure from Southern California, melting into melancholy chords evocative of Atlanta’s emo-trap sing-raps that guest rapper Lil Baby is best known for. Despite this, Staples manages to synthesize the work of more than a dozen different producers—many virtual unknowns—with a persistent ennui shared by all the cooks in the kitchen.

Much of that can be attributed to Staples’ delivery of lyrics that belie an existential exhaustion. The detail-rich raps serve less as a tour guide than they do a memory map. When he raps bars like, “Nowhere to go when we in the cage/Sometimes life tastes bittersweet,” as he does on “Lemonade,” who is that for? It may be a given that these lyrics about this specific neighborhood in Long Beach, California aren’t meant to be universal. But the unvarnished portraits that he paints of his hometown connect with people around the world not because those experiences feel shared, but because they feel honest, and worn with pride. The difference here is that those portraits seem to have lost some of their luster, even for him.

If there’s a single set piece that can speak to each of the disparate corners of Staples’ audience, it’s “When Sparks Fly,” the album’s most complete standalone statement. On its surface, it’s a standard street love song, built atop a sample of Lyves’s ethereal ballad “No Love,” before a different, more surprising voice emerges. This is a lover’s lament told from the perspective of a personified firearm, bemoaning his capture by the police from its hiding place. It captures a sense of longing that Staples is typically unwilling to reveal in the first person, reaching beyond the standard refrain of “free the homies” to depict how those on the outside can often feel just as trapped.

Staples’ disillusionment comes into sharp focus on “The Spirit of Monster Kody,” a 45-second skit that’s voiced by Sanyika Shakur, fka “Monster” Kody Scott, an infamously violent member of the Eight Tray Gangster Crips who wrote an autobiography about his troubled life. In his speech, Kody speaks of defying expectations and drawing inspiration from the legendary rebel Joseph Cinqué. Free of additional context, it’s powerful, even inspiring. But what Staples leaves unsaid is that despite his triumphs, Kody’s end was as tragic as his beginning—last summer, his body was found decomposing in a tent at a homeless encampment near San Diego.

Staples has been consistently clear about the distinction between his work and what an “entertainer” like Drake does. To call this album entertainment would almost feel disrespectful. This is a document of a young man’s pain, a chronicle of his disillusionment barely disguised by his deadpan voice. Even the things that once grounded him—the people and places that shaped him into who he is—look different now. Ten years into a career of recounting the decisions he made to get here, he has more available options than ever—and he finally appears ready to move on.

“I feel like a lot of my work has been an anthology of my neighborhood and my past, and I think this is kinda the end of that for me,” Staples recently told New York radio station Hot 97. This contextual clue offers some clarity to his weary tone on Ramona Park Broke My Heart, one worthy of an epilogue to what’s been a compelling depiction of an overlooked corner of the world. It might not meet the extremely high bar set by his best work, but it’s almost certainly him at his most emotionally vulnerable.

0 comments:

Post a Comment