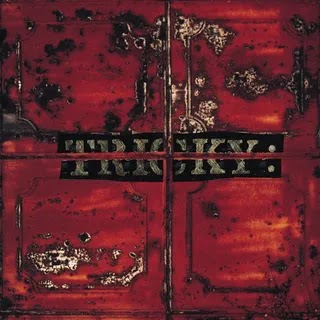

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the Massive Attack associate’s 1995 debut, a gloomy unicorn of contemporary UK pop.

Tricky’s Maxinquaye brought grinding doubt and psychedelic waves of paranoia to the radio at a time when Oasis were telling us we would live forever and Blur were living that Parklife. Tricky would go on to release masterful music after: Nearly God and Pre-Millenium Tension, both from 1996, push at the boundary between enjoyment and unease, aching and itching in their weed-infused paranoia. But neither is as elegantly chaotic as Maxinquaye, an unrepeatable record so unbelievably wrong it could only be right. Maxinquaye is a work of beautiful disorder and lucky mistakes. Its success was like the extraordinary run of an underdog sports team to the final: wildly unlikely yet oddly fated.

The crux of Tricky’s early music is the combination of his own deep-smoked vocals and the wispy, melancholy delivery of Martina Topley-Bird, a teenager who Tricky met when she was sitting on a local wall, drunk on cider, after finishing her exams. That chance meeting alone was essential to the genesis of Maxinquaye. Without other moments of serendipity, Tricky might never have become a solo artist. He was born Adrian Thaws in Bristol, England, and his early life was impossibly hard: His mother, Maxine Quaye, died when he was four and his father was rarely around. Tricky met Milo, who would later become a DJ for legendary local soundsystem the Wild Bunch, when he was just a boy; this connection led to him coming on board as a rapper for the group, which in turn gave birth to Massive Attack. While never quite at the center of the Massive Attack world, Tricky featured on the band’s 1991 debut Blue Lines and was sufficiently in their orbit to ask their management for cash when cash was needed.

It was Mark Stewart, the Bristol musician who founded the Pop Group and lived with Tricky in the 1990s, who suggested that Tricky should try to “blag” money from Massive Attack’s managers to make a solo record. It worked, with half of the money going to booze and the remaining £300 to record “Aftermath,” a devastating work of hip-hop blues that Massive Attack apparently passed on. (As ever with Tricky—not the most reliable narrator—it is worth hearing these claims with a skeptical ear.)

“Aftermath” was a statement of intent: a mixture of midnight keyboard trills, rockabilly guitar riffs, haunting flute, and dub basslines that lopes to a dusted boom-bap beat with the menace of a stoned tiger. It could have been one of the classic debut singles of the early ’90s. Yet “Aftermath” languished, unheard beyond its initial white-label release in early 1993, until Tricky’s cousin suggested he try to secure a record deal a couple of years later. Julian Palmer, who ran the Fourth & Broadway imprint within Island UK, was a fan of “Aftermath” and convinced Island to fund recording sessions with Howie B, a Scottish producer who had worked with Siouxsie and the Banshees and Soul II Soul. The sessions produced “Ponderosa,” a bhangra-influenced evil lullaby whose percussive gamelan lurch threatened to drag the song upbeat, even as the lyrics painted a picture of troubled minds and temporary oblivion. “Ponderosa” persuaded Island to sign Tricky, although legal and managerial wrangles detached Howie B from the project and shelved an early batch of songs.

Tricky and Topley-Bird, by now a romantic as well as a musical couple, were on their own to record an album, a process Tricky proclaimed he knew nothing about. In another moment of fortune, he asked Mark Saunders, a producer on Massive Attack associate Neneh Cherry’s debut album, to collaborate on the record, attracted by his handiwork on the Cure’s Wish and Mixed Up. It was—as Island understood it—a fairly straightforward engineering gig. “I don’t think the record company really knew what Tricky did,” Saunders told Sound on Sound in 2007. Island, he says, thought they had signed a DJ/producer who would be perfectly capable of making his own album and had furnished him with a small studio’s worth of equipment in a house in London’s Kilburn to do so. “However, the first day I went to his place to work, it was just littered with vinyl all over the floor,” Saunders explained. “He said, ‘OK, let’s sample this record,’ and I said, ‘Yeah, sure, go ahead.’ He said, ‘No, no, I don’t do any of that stuff.’”

In his book Hell Is Round the Corner, Tricky paints a rather different picture of the album sessions. According to him, Saunders came in at the end of the recording process, after Tricky had produced most of the tracks himself, to mix the album. He also claims that Saunders—“a corny old dude”—didn’t understand the music on Maxinquaye and frequently added unwanted guitar parts to the songs, which Tricky later wiped.

Whatever the case, recording Maxinquaye was a deeply peculiar experience for all involved. Saunders called the album “a complete un-learning experience,” while Tricky was surfing on the power of musical naivety. “Being naive I think is how you construct new music,” he told The Guardian. “When you start thinking too much what is it you’re doing? You’re just making an album. You’re not doing brain surgery.” His aim was simple: “To do an album that’s going to fuck everybody up. No compromise whatsoever.”

When I say that Maxinquaye is unique and unrepeatable, this is what I mean. Tricky’s naivety meant that he approached making music as no one else would, rejecting any kind of musical orthodoxy. “If someone can tell you how they did a song, I don’t trust them,” he once told Rolling Stone. “It should be a magical process.” Saunders relates tales of Tricky asking him to sample two songs that ran at different tempos and in different keys; of Tricky picking from records scattered around his flat seemingly at random; of rough mixes and rotten sounds left in to fester; of borrowing a Portishead sample, stoned, and forgetting about it. Sometimes—as on “Strugglin’,” a remarkably bleak work of slo-mo hip-hop that feels like Houston chopped-and-screwed oozing up through a Bristol gutter—Tricky’s singular choices could be made to work by bending and de-tuning the samples at hand. At other times, this would prove impossible, and Tricky would move swiftly onto the next idea bubbling inside his head.

“Tricky’s genius is just being Tricky,” Saunders explained in 2007. “He had no idea of pitch whatsoever and also not much regard for any kind of timing. He really couldn’t get the concept of four-bar, eight-bar, 12-bar sections; that stuff meant nothing to him.” On this point, Tricky largely agrees: In Hell Is Round the Corner, he proudly explains that he “didn’t know how to make music.” “I had no rules,” he wrote. “I’ve always had weird time signatures, not because I’m trying to do it—some artists use them to try and make their music weird. My music is weird because I don’t know what I’m doing.”

You might expect that Maxinquaye would be the fearsomely unapproachable work of a hip-hop malcontent, a Trout Mask Replica for the Blue Lines set. But somehow these fiercely amusical ideas cohered into exquisitely lush almost-pop songs that chill in their intent while seducing with their delivery, a little like the RZA’s perfectly realized avant-hip-hop beats on Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). Even at its most experimental—on “Strugglin’” or “Overcome”—Maxinquaye is never less than listenable, while the Michael Jackson-referencing, Britpop-baiting “Brand New You’re Retro” is a poisonous pop dart to the neck.

It would be easy to assume that Saunders deserves credit for the album’s cohesion. “Just for the Hate of It (Rough Monitor Mix),” a precursor to “Abbaon Fat Tracks” included on the 2009 deluxe edition of Maxinquaye, stumbles and lurches, a mess of badly interconnecting elements, while the finished “Abbaon Fat Tracks” glides, weaving together disparate elements—telephone tones, lurching piano, and what sounds like a heavily phased guitar—in a silken mesh. But listen back to an alternate mix of “Aftermath,” taken from the song’s 1993 white-label release, and it is obvious that the irresistible hooks and pop smarts were there from the beginning, rendering the layers of tape hiss and recorded gloop irrelevant.

More than anything, Maxinquaye came from hip-hop. While recording the album, Tricky was invested heavily in the Geto Boys’ horror-scarred Southern rap, and hip-hop runs in deep currents underneath Maxinquaye, from the scuffed breakbeats to Tricky’s mumbled raps. But Tricky has broad musical tastes—he once named Frank Sinatra’s “That’s Life” and “Lalla Laroussa” by Algerian rai singer Cheb Anouar among his 10 favorite songs—and these pushed Maxinquaye into unlikely new spaces.

Tricky considered Maxinquaye to be “new music,” and you can see what he means. He’s not recreating anything, though you can hear a debt to everything from the Specials’ pointed ska fusions to labelmate PJ Harvey’s heart-on-sleeve bluesy intensity. At the same time, Maxinquaye wears the sharp thrill of perfect pop music. Tricky would claim to be annoyed by the success of Maxinquaye—which reached No. 3 in the UK charts, turning it into what he called ”a coffee-table album”—but he was always a fan of more adventurous pop artists, notably Kate Bush, who he called “in the same league as John Lennon.”

In assimilating these expansive tastes, Tricky was surely influenced by his upbringing in Bristol, the culturally adventurous Western English city that helped birth Massive Attack, Portishead, Flying Saucer Attack, Rip Rig + Panic, Smith & Mighty, John Parish, Roni Size, and Krust. Tricky may claim to have little time for talk of a Bristol scene (and very little time for Portishead) but it seems noteworthy that this musical free spirit grew up in a city where the Wild Bunch mixed punk with R&B and Massive Attack added reggae, soul, and downtempo hip-hop to their soundsystem stew.

Topley-Bird’s vocals also played an important, if perhaps unconscious, role in sweetening the Maxinquaye pill. Tricky wanted to foreground a female voice in the role of “my mum speaking through me,” and many of the lyrics were written from a woman’s perspective, adding a prescient sense of gender fluidity to the record. Where Tricky’s voice is rough and phlegmy, with all the silent menace of the powerful, Topley-Bird’s is a cobwebbed whisper, somehow both lush and fragile, like the thinnest silk thread.

Don’t mistake this delicacy for weakness, though. On songs like “Brand New You’re Retro” or “Black Steel,” Topley-Bird has an incredible swagger, while on “Abbaon Fat Tracks,” she is alarmingly blank and predatory. Tricky used different vocalists on two Maxinquaye songs—Alison Goldfrapp on “Pumpkin” and Ragga on “You Don’t”—and, to my mind, they feel slightly off, like representatives of a parallel universe where Tricky and Topley-Bird never met.

Topley-Bird also brought the lion’s share of vocal melody to Maxinquaye, spinning off improvised tunes like velveteen rabbits from a hat. Rather than suggesting that Topley-Bird listen to his tracks in advance and reflect on what she would sing, Tricky would apparently hand his teenage foil a set of lyrics and send her off to the kitchen to improvise a take. It was, Topley-Bird said, “totally instinctive.” “There was no time to drum up an alter ego,” she told The Guardian. Yet the melodies she came up with are otherworldly and sublime, from the hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck revolt of “Strugglin’” to the disinterested disgust she lays on “Abbaon Fat Tracks.”

These various themes—happy accidents and wide tastes, casual melodic power and genre ambivalence—collided on “Black Steel,” a strutting, guitared-up half-cover of Public Enemy’s “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos” that dented the UK charts. The track started with a scratchily recorded drum loop from “Rukkumani Rukkumani,” taken from Indian film composer A. R. Rahman’s Roja soundtrack, which Tricky had received from the mother of his former girlfriend and to which someone—possibly Saunders—added a backward guitar riff. When it came time for Topley-Bird to record her vocals, Tricky couldn’t be bothered to write them out in full, so Topley-Bird ended up using just the song’s first verse, to which she improvised one of her most powerful melodies, twisting and swooping like a bird escaping from its cage. Techno-rock act FTV, who Tricky had met at a gig, added snarling guitar and Sex Pistols-style drums to create a supremely unlikely—and yet entirely fitting—Bollywood/rock/techno/hip-hop take on the Public Enemy classic.

Maxinquaye was an immediate sensation in the UK, selling 100,000 copies in its first months of release. It even made an impact in the U.S.—something almost unknown for a hip-hop-leaning act from the UK at the time—and Tricky teamed up with Gravediggaz for The Hell EP, cementing a stylistic union with RZA. For an album so rooted in Bristol, Maxinquaye’s reach remains surprisingly universal: Tricky might have claimed that Beyoncé had never heard of him when she invited him to guest at her 2011 Glastonbury headline slot, but without the critical and commercial success of his debut, that bizarre cameo surely would never have happened. Such public recognition came at a price. Alongside the output of Portishead and Massive Attack, Maxinquaye would come to be seen as a leading work of the trip-hop movement, a stylistic tag that Tricky hated. “I don’t really know what trip-hop is, I think it’s bollocks to be honest,” Tricky told Dummy in 2013. “People call Morcheeba trip-hop don’t they? Well I’ve never listened to them.”

You can understand his distrust of the label. Tricky’s music is far darker and more abstruse than the soft-soap hip-hop beats of Morcheeba or Sneaker Pimps; it is far more claustrophobic than Massive Attack’s celebrated trio of ’90s albums; and there is little to no connection between the scorched velvet of Tricky and Topley-Bird’s vocal pairing and the operatic intensity of Portishead’s Beth Gibbons. Tricky had poured his whole life into Maxinquaye and had no desire to see his music watered down by weakling imitators armed with a sampler and a couple of library-music albums.

Even if his debut were trip-hop, Tricky would spend the next few years recording an increasingly bleak collection of records intended to “kill all that Maxinquaye bullshit,” resulting in the noxious paranoia of Nearly God and the vibe-suffocating desolation of Pre-Millenium Tension. With the ratcheting nerves of Tricky’s subsequent albums—2020’s Fall to Pieces was his 14th—Tricky’s star has faded somewhat, and he has bounced label to label and collaborator to collaborator. For almost 30 years, listeners have been waiting for Tricky to return to the monumentally anomalous charms of Maxinquaye, a record regularly cited among the best albums of the ’90s.

They will wait in vain. To revisit such singular territory is unthinkable, like wishing lightning would strike twice with a slightly updated color scheme. Even if Tricky wanted to return to the sound of Maxinquaye, he almost certainly couldn’t. Maxinquaye was based on musical instinct—on not knowing what was right, and caring even less. But chance encounters happen only once, and innocence lasts only so long. In recording Maxinquaye, Tricky inevitably started to absorb the conventions of musical production, slowly strangling the goose even as it laid the golden egg. Fall to Pieces is a great album, agonizing in its wounded depths; but, the odd anarchistic touch aside, it is a fairly orthodox record, one that appears to know all about eight-bar sections, consonant harmonies, and the other musical conventions to which Tricky was once so gloriously indifferent.

Like fashioning a house of cards in a strong wind, Maxinquaye held its destruction in its own creation and its failure in its success: a borderline unclassifiable work that was Tricky in both name and nature. If we can no more remake Maxinquaye than land another first man on the Moon, it remains a magnificent singularity, a full-on solar eclipse of an album that blotted out all precedent to seek refuge in the shadows.

0 comments:

Post a Comment