Today on Pitchfork, we are celebrating the artistic bounty of Stevie Wonder with five new album reviews that span the breadth of his remarkable career.

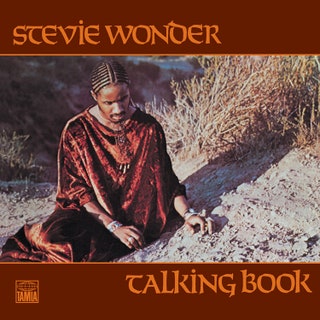

In 1972, Stevie Wonder released the first two albums in a legendary series of LPs that would affirm the breadth of his talent and his signature sound as a songwriter: Music of My Mind and Talking Book. It’s not that Wonder’s 13 prior Motown recordings failed to show off his unique voice and personality, just that the blind polymath felt unfairly limited by Motown’s need to dictate what he could sing about and how it could be produced. By the end of the 1960s, the recording industry’s system of tightly controlled “hit factories” was losing ground to the more anarchic creativity of the folk-rock, jazz fusion, and singer-songwriter movements. Motown had been calling Wonder a genius since he was 12 years old but seemed afraid to give him the freedom to prove it.

Aside from some pop-R&B singles crafted by in-house production teams serving Black radio’s bottom line, what Berry Gordy wanted from a Stevie Wonder album was inoffensive pop covers and modern standards aimed at the adult crossover market. Ramping up to the glorious suite of original material that would comprise Talking Book were Wonder’s initial attempts to completely control his sound on 1971’s Where I’m Coming From and Music of My Mind. The singer had spent 10 years soaking up musical influences from church, television, radio, and a wide range of other performers before breaking free of the sonic straightjacket Motown imposed on all its artists.

The results were remarkable. Even the titles and cover art of what would become Wonder’s breakaway albums telegraphed his determination to start presenting his own ideas in his own way. The big afro looming above image-projecting sunglasses on Music of My Mind, followed by Wonder wearing African robes and braided cornrows on Talking Book, shows him in a proudly Afrocentric state. Despite physical blindness, he reveals himself to his fans as a seer; despite seeing all races as equal, he won’t ignore how racial and social injustice disproportionately oppress Blacks. Recording new music outside the vintage Motown system while using a revolutionary computerized instrument to do so helped drive these points home. If the Beatles’ music could be, by turns, sexy, spiritual, and political, so could Stevie Wonder.

But before we reassess the tracks on Talking Book, we need to remember what Mr. Steveland Morris would have been hearing on R&B and pop radio between 1969 and 1972. Back then, Black singer-songwriters like Isaac “Black Moses” Hayes, Sly Stone, and fellow Motown rebel Marvin Gaye were iconoclasts who were nonetheless commercially successful. The rising Black Power and anti-Vietnam War movements added a new seriousness and emotional urgency to popular music which the usually conservative radio stations began to embrace. After making scores of hits as a house musician at Stax, Hayes went solo to invent the trippy R&B concept album in 1969, then in 1971 became the first Black composer to win an Oscar with his pop-chart topping soundtrack to the movie Shaft. Sly Stone—a radio DJ, record producer, and bandleader—took the psychedelic funk of the Bay Area to the top of the charts when quirky singles from Dance to the Music (1968), Stand! (1969) and There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971) achieved heavy rotation on both Black and pop radio.

Then, much to everyone’s surprise, Wonder’s labelmate Marvin Gaye joined this musical revolution in 1971 by defying Motown’s ban on protest material with What’s Going On. Hearing Gaye’s gorgeously orchestrated broadsides against war, pollution, and racism get massive praise and airplay during the repressive Nixon years only increased Wonder’s desire to make equally heartbreaking hits about love and social crisis. When discussing Wonder’s professional evolution, much has been made of his ability to receive millions in royalty earnings (held in trust) and simultaneously renegotiate his elapsed Motown contract when he turned 21. But there was much more involved in Wonder’s evolution from a cute adolescent singing “Fingertips Pt. II” during the closing credits of Annette Funicello’s Muscle Beach Party to the mature artist who debuted “Superstition” while touring with the Rolling Stones in 1972.

Wonder had started touring internationally by age 13. In 1963, after British TV producer Vicki Wickham and pop diva Dusty Springfield saw Wonder perform at a Paris theater, they immediately invited him to England to sing two songs on Wickham’s top-rated music show, Ready, Steady Go! Wonder thereby became the first Motown artist to appear on RSG!, which helped break the Motown sound to millions of British fans. The Rolling Stones were on that same episode, and Mick Jagger remembers chatting about music with a “13 or 14-year-old” Wonder at the TV studio as they waited to perform to a fashionable crowd of dancing teens during the live evening broadcast. Over the years, Wonder befriended many British musicians during his tours, and it was usually a case of mutual admiration. It would have been typically shrewd of Wonder to pay close attention to Jagger, Donovan, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Marc Bolan, and other British stars influenced by American pop music, attentively noticing how they adapted chords and tempos to make various Yankee blues and folk styles their own. Thus, if Wonder’s “Maybe Your Baby” on Talking Book evokes mutated chords and rhythms from Donovan’s “Season of the Witch”—or inserts layered vocal ad libs reminiscent of those Sly Stone used on “Family Affair”—it is only the sincerest form of flattery.

Another aspect of Wonder’s development as a songwriter that is too often glossed over is the contributions of his female collaborators. In the 1960s, Motown stalwart Sylvia Moy co-wrote several of Wonder’s most memorable singles. “I Was Made to Love Her,” “My Cherie Amor,” “I’m Wondering,” and even “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)”—the dance tune that reportedly kept Berry Gordy from dropping Wonder after his voice changed—are each marked by Moy’s eloquent turns of phrase and elegant yet emphatic vocal phrasing. What Wonder picked up from Moy and other female artists he admired was a kind of romantic gallantry expressed in genteel, wistful, and contemplative ways. When Wonder and then-wife Syreeta Wright co-wrote all nine tracks on 1971’s Where I’m Coming From, the single “If You Really Love Me” incorporated sudden shifts in tempo, mood, and phrasing that enhanced lyrics describing all the frustrating ups and downs of romance. “I Wanna Talk to You” was Wonder’s first deep exploration of the racial divide, daring to imagine a lyrical confrontation between old Southern whites and modern blacks. An effort was made to match lyrical content with tempos and melodies that would deepen meaning on each track.

Ultimately, this approach to songwriting would suffuse both Wonder’s political and romantic material, letting him insert elements of hippie mysticism, science-fictional speculation, and interdenominational spirituality. On Talking Book, “Big Brother” has Wonder quietly crooning, “You’ve killed all our leaders/I don’t even have to do nothin’ to you/You’ll cause your own country to fall,” over an irresistibly bouncy track of Moog baseline buoyed by cheerful clavinet and harmonica arpeggios. Inspired by George Orwell’s futuristic dystopian novel 1984, “Big Brother” delivers some of Wonder’s harshest observations about Nixon’s America with sophisticated and somehow soothing irony. Similarly, the scenarios of love-gone-wrong addressed in “Tuesday Heartbreak” and “Maybe Your Baby” stand out in terms of how Wonder articulates the painful ambivalence lovers often feel. Throughout “Tuesday,” the singer oscillates between breezy certainty that his love can win her back and his flip resignation to her wanting to leave him for another. In this way, the unavoidable cruelty of unrequited love is effectively juxtaposed against the necessary cruelty of telling someone you’ve found someone else.

During the early 1970s, British bass player and programmer Malcolm Cecil was helping Wonder incorporate the sounds of the Original New Timbral Orchestra (T.O.N.T.O) alongside American engineer Robert Margouleff. Cecil watched Wonder compose songs at different times with both Syreeta Wright and Yvonne Wright (unrelated). Speaking to Chris Williams for Okayplayer in 2019, Cecil recalled, “Yvonne would sit next to him at the piano and whisper words into his ear while he was singing.” Syreeta and Yvonne ended up having two tracks each on Talking Book. All four songs are about the trials of love and as such are amazingly synergistic in sound and mood. Significantly, the ex-wife Syreeta wrote the “I’m movin’ on” songs “Blame It On the Sun” and “Looking for Another Pure Love.” The latter is optimistic with a twist—the title refers to a surprise phone call in the first verse that ends a relationship, leading the singer to seek a replacement. The “pure” in the lyric is an important qualifier because the song’s protagonist—male or female—wants nothing insincere. But the records with Yvonne are about romantic beginnings, not endings. “You’ve Got It Bad Girl” is a cautionary tale about a woman not so sure she should give in to passion.

At this stage of his career, Wonder himself would admit to the press that he preferred writing music to lyrics. While promoting Talking Book in 1973, Wonder proudly confessed to Tony Norman of NME that the album’s No. 1 pop single “Superstition” was “really the first successful tune I’ve written for myself.” The first demo for “Superstition” was a collaboration completed in a single day after starting as a studio jam session between Jeff Beck on drums and Wonder improvising on piano. Wonder intended to write a tune for Beck in exchange for his adding guitar to some studio tracks; he even told Beck he could release his cover of “Superstition” first. But Beck’s subsequent album was delayed, and Berry Gordy insisted that “Superstition” be the lead single for Talking Book in October 1972.

It can be hard to tell the order in which tracks were selected for each of Wonder’s albums between 1971 and 1976 because of how prolific he and his collaborators were in the studio. Cecil and Margouleff typically over-recorded whenever Wonder was around. Days blended into nights for the energetic Stevie, who was exhilarated to have access to the pair’s experimental genius, as well as to the world’s largest (and only) polyphonic analog synthesizer. Working with T.O.N.T.O.’s massive array of Moog, Arp, Oberheim, and other synth modules could be slow and buggy. But it afforded Wonder a level of control over the recording process that was crucial to his getting the sounds in his head onto tape. Also, making his keyboard mimic any instrument known or unknown was a great goad to his imagination. Cecil’s goal of enabling musicians to have complete control of every technological step in the recording process dovetailed perfectly with Wonder’s desire to create music with fresh sounds for a challenging new decade. He’d gotten started by adopting the versatile Hohner clavinet as his signature keyboard. (One can’t overestimate the importance of a memorable and quasi-proprietary keyboard sound to an innovative recording artist. Imagine “96 Tears” without the Farfisa keyboard or “A Whiter Shade of Pale” without the Hammond B3 organ!)

What Talking Book did for synthesizer-based music was humanize it to a greater extent than ever before. How Wonder recorded vocals and analog instruments throughout the album was as important as how he deployed the synthesizers. The tiniest shift in inflection, a whispered aside, or an improvised solo had meaning and purpose. Even the vocal encouragement he gives to Jeff Beck during his guitar solo on “Lookin’ for Another Pure Love” adds focus and soulfulness to the composition. In “Blame It on the Sun,” hearing the naked purity of acoustic piano against the anachronistic harpsichord fills, and the Theremin-flavored pitch of T.O.N.T.O.’s nuanced wail serve to frame Stevie’s lead vocal perfectly. Multi-tracked backup vocals are underscored with skeletal tonal colors that warm them just enough to give an impression of unshed tears. These little sonic surprises happen throughout the album, giving it a lasting sense of intimacy and spontaneity.

The transition from Talking Book to Innervisions felt neither abrupt nor strained because some of the songs on both albums had arisen from the same sessions. Cecil and Margouleff always kept a quarter-inch tape reel running to preserve inspired jam sessions or random demos. That is part of the magic of this period when everything was moving so fast.

Today, most people would agree that what Talking Book did for Wonder was raise public expectations for all his subsequent work. The operatic intensity of downtempo arias like “Blame It on the Sun” or “You and I” were offset by the funky grind of “Maybe Your Baby” and the sardonic playfulness of “Big Brother.” This strategic way of counterbalancing different musical attitudes on the same LP would continue through 1974’s Fulfillingness’ First Finale and 1976’s Songs in the Key of Life. In retrospect, the combination of tunes cherry-picked for the Talking Book package became the artistic standard against which all future albums by Stevie Wonder would be measured.

0 comments:

Post a Comment