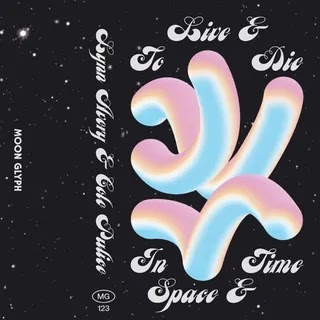

As gentle as cherry blossoms on a spring breeze, the Minnesota musicians’ lush compositions for saxophone, piano, and synthesizer convey a wealth of feeling.

To Live & Die in Space & Time is Lynn Avery and Cole Pulice’s debut album as a duo, but the Minneapolis musicians have been making music in parallel, and occasionally together, for some time. Recording since 2017 under the alias Iceblink, Avery first developed a cozy, playful style of hypnagogic pop. The tape-warped psychedelia of her early releases hinted at Broadcast and Boards of Canada, and on 2020’s Carpet Cocoon, she folded new age, folk, and jazz into the mix, adding Pulice and fellow Minnesotan Mitch Stahlmann on saxophone and flute. Pulice concentrated their 2020 solo debut, Gloam, on the meditative sounds of tenor saxophone and softly glowing electronics; recording live without overdubs, they traded Avery’s lilting chord changes and lysergic easy listening for drone-based minimalism and airy soundscaping. Avery, Pulice, and Stahlmann also made a trio record together in 2020, stretching woodwinds and synths into gauzy abstractions reminiscent of Visible Cloaks. But on To Live & Die in Space & Time, Avery and Pulice tighten their focus, striking a careful balance between melody and mood.

Like almost everything they have done together, To Live & Die in Space & Time is as gentle as cherry blossoms on a spring breeze. Pulice plays saxophone and wind synthesizer, Avery plays piano and synthesizer, and both are credited with additional electronics, which they tend to daub on in translucent background layers. The music is too lush to be called minimal, at least by the term’s more austerely digital connotations, but they keep their tools simple, their tempos slow, and their playing unfussy. Channeling a mix of whimsy and wide-eyed wonder, they come off a little bit like contemporary heirs of Penguin Cafe Orchestra, a Brian Eno-produced group that spun bits of folk, jazz, and classical into a loose ambient weave; another reference point might be the new-age jazz of the British group Dif Juz’s 1985 album Extractions and their Elizabeth Fraser collaboration “Love Insane.”

It’s a short record, just 27 minutes, and it opens with the shortest of the four songs: “Belt of Venus,” setting Pulice’s circular melodies over a muted, lazy spiral of arpeggiated synth. Their playing is so lyrical that it practically takes on the qualities of verse. The initial phrase, searching and higher in pitch, voices a question; a second, half an octave down, offers a contemplative answer. Despite the music’s tranquility, it’s not as simple as it seems: Bursts of delay occasionally resemble hammering woodpeckers, and the background is a perpetually shifting moiré of dynamic colors and textures. Not much longer, “Plantwood (Day)” is similar in form and feel, with Pulice’s saxophone gracefully garlanding a watery, waltz-time arpeggio. This time it’s Avery’s piano that assumes the center of the frame. Patiently, she lays down soft yet blocky chords, then lets them fade, until you’d almost forgotten there was a piano in the room at all. She changes the voicing almost every time, shifting the tonal center almost imperceptibly; like Ryuichi Sakamoto, she conveys a wealth of feeling out of the smallest gestures.

On “Stained Glass Sauna,” they sink deeper into their invented soundworld. Pulice’s synthesized flute lends an unmistakably pastoral air; a gently propulsive synth pattern suggests dub techno played on a deep-sea marimba. The sense of immersion becomes total on “The Sunken Cabin (Night),” a melancholy, 13-minute fantasia that recalls Nala Sinephro’s brooding “Space 8,” and marks the dreamy outer limit of the album’s ambient new-age excursions. Over soft, sustained synthesizer pads, Avery and Pulice engage in a relaxed improvisational exchange. Though the saxophone is typically a lead instrument, given its range and its cutting timbre, it doesn’t dominate here; Pulice leaves ample space for Avery’s piano, and vice versa. Their mutual give and take feels both natural and exploratory. Avery begins by mulling over a single chord but gradually moves outward, as though mapping unknown territory.

To Live & Die in Space & Time often feels like overhearing a conversation between two close friends, and listening to “The Sunken Cabin (Night),” can seem like eavesdropping on their most intimate thoughts. An air of mystery abides, and there are occasional intimations of darkness: Occasionally, Pulice will bend a note on their saxophone, hinting at unspoken pain. New age and ambient alike can sometimes fall prey to the facile or the saccharine, but not here. By tempering sunny idyll with passing shadows, Avery and Pulice achieve a depth of expression that’s hard to quantify but easy to recognize: It simply feels true.

0 comments:

Post a Comment