On his 1977 solo debut, the American flutist probes the possibilities of his instrument: multi-tracking it, pairing it with harpsichord, and playing alien, unadorned Ellington standards.

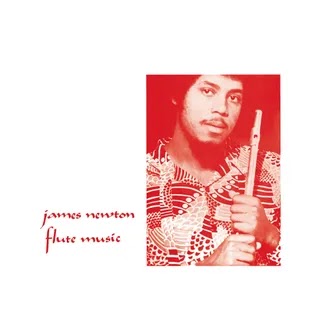

In late 1984, James Newton climbed through New Mexico’s Carson National Forest, near where Georgia O’Keeffe lived, to play the flute amid the din of crickets and twittering birds. He recorded himself using power generated from a motorcycle battery. Newton was “thinking about the flute as an instrument found in all world cultures,” he said. The resulting album, Echo Canyon, captured long threads of improvisation bouncing off the rock around him, forming walls of sound that seemed just as ancient. In the years since, Newton has continued to use the flute as a probe to poke at the sublime. He began laying that groundwork years earlier, in his solo debut Flute Music, reissued this year for the first time since its 1977 release.

Newton tries out different structural frames for his instrument throughout Flute Music. On opener “Arkansas Suite (Bennie),” he multi-tracks it into two minutes of fluttering chorus. A fleeting architecture forms: When one layer rises above the rest, those beneath it support its exploration of melody, or its slow glide into a single sustained note. It sounds like a convocation, highlighting the flute’s proximity to the human voice. There’s no layering on the song’s second part, “Arkansas Suite (Solomon’s Son).” Instead, Newton hems his flute in with the help of a harpsichord, whose metallic sound holds the flute’s wandering like an enormous wire cage for a rare bird. He uses percussion on “Darlene’s Bossa” to the same effect, letting his flute embroider the song’s steady samba rhythm. These structures provide a sort of anchor for Newton, ground that he can use to contrast his flute’s airborne freedom.

The most exciting moments on Flute Music happen when Newton is fully unbound. “Skye” begins with martial drums and rattling chimes that sound at first like swords unsheathing. They quiet when Newton’s flute emerges as a calming force, compelling the percussion into order. With the addition of guitar, bass, and percussive embellishments, Newton lets the song unfurl like a changing landscape watched from a train window. He adjusts his playing so that the tone wavers between mournful and agitated, his blowing ragged and torn one moment but clear and full the next. On the album’s B-side is “Poor Theron,” an 18-minute free-jazz experiment. Rattling bells, trombone bursts, and long piano riffs often replace Newton’s flute altogether; when it returns, it sounds like a scream.

The record’s penultimate track is a version of Duke Ellington’s jazz standard “Sophisticated Lady.” Where singers like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday imbued the song with complicated feelings of longing and ennui, Newton’s take is barren and strange, the only track on the record that features nothing beside his flute. Newton’s career is studded with other references to pioneering artists, including a full-length ensemble tribute to Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, and, later, one to Frida Kahlo. Looking back at his debut, it’s clear how those influences would come to figure into his goals as an artist and jazz innovator himself—to find out out how to push the expressive limits of his instrument as close to transcendence as possible.

0 comments:

Post a Comment