To celebrate the cult classic’s 50th anniversary, a new collection of Cat Stevens’ music for the film—including songs later covered by Elliott Smith and others—finally becomes widely available.

Hal Ashby’s 1971 film Harold and Maude initially flopped because its ideal audience was just being born. The script by Colin Higgins, who would later write and direct movies including Foul Play and 9 to 5, told the story of the relationship between depressed and suicide-obsessed 19-year-old Harold, played by Bud Cort, and the cheerful 79-year-old Maude, played by Ruth Gordon. Harold and Maude poked fun at those living the straight life and made pointed critiques at the military and the status obsessions of the privileged. One set piece laid out the ethical imperative of ecology and another suggested that sexual expression was a path to freedom and understanding. On paper, it seemed like exactly the kind of film the counterculture would embrace.

The timing was off, though, and the film tanked, both commercially and critically. Harold and Maude struck critics as cloying and audiences went elsewhere. But it built a cult following in second-run houses through the 1970s and reached a new audience a few years later, when the children of those who rejected it upon release found the film’s VHS box on the wire shelving of their local video rental shops. This younger cohort was just the right age to discover the movie—early to mid teens, when one experiences the first flush of existential angst and, perhaps, mixes excitement about the wonders of the world, like Maude, with moments of self-doubt and despair, like Harold. Watch it now, and you may notice that Harold and Maude looks like an indie flick from the 1980s or ’90s. An era of filmmakers, including Wes Anderson, Mike Mills, and Paul Thomas Anderson, found Ashby’s film seeping into their own work.

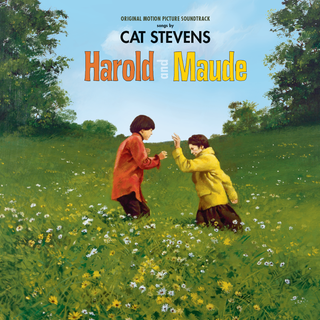

The surprising thing about the film’s soundtrack is that it didn’t exist until 2007. In the movie, the songs by Cat Stevens serve as a kind of Greek chorus, reflecting Harold’s spiritual development and the evolution of their relationship from friendship to romance. (Stevens, born Steven Georgiou, converted to Islam in 1978 and took the name Yusuf, but it’s his stage name that appears on this record’s cover.) The music is so integral to the story it would have been easy to assume that a soundtrack had existed all along.

But Stevens was hitting a peak in popularity when Ashby approached him about using his songs, and he worried that the soundtrack, which compiled material from the two records he released in 1970, Mona Bone Jakon and Tea for the Tillerman, might confuse his audience. So no official soundtrack album was issued until 2007, when Cameron Crowe assembled a limited reissue on his Vinyl Films label. Now, a different assemblage put together for the film’s 50th anniversary finally makes it widely available.

To listen to Cat Stevens is to figure out where you stand on music whose earnestness tips over into naïveté. If you love his work, you almost certainly need to have gone through a time as a young person where you obsess about what life means and what makes it worth living—to “take the world apart and figure out how it works,” as Doug Martsch put it in Built to Spill’s “Car.” And it probably helps if that surge of curiosity about exploration was accompanied by at least a little joy. And—this is crucial—you would need the capacity to look back on this heady period and feel some love and empathy for the person who dreamed those dreams. If all that comes together, you may find much to admire in this collection, which frames a world where love is better than a song, the answer lies within, you think you’ve seen the light, there’s a million things to be, and Lord, though your body has been a good friend, you won’t need it when you reach the end.

Two of these songs were sketched out before Harold and Maude but completed once Ashby had enlisted Stevens for the soundtrack, and both are inseparable from the film. “Don’t Be Shy,” just a fragment when Stevens was first contacted by Ashby, is a plea to tell the world who you are and what you need; it features a beautifully delicate piano part that sounds like raindrops. “If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out” is its companion, and Ashby thought so much of it he made recurring use of it in the film and allowed his characters to sing it on screen.

The rest of Stevens’ songs were recorded before Harold and Maude and placed on his albums, yet they, too, now belong to the film’s world. Where these pieces are mostly about human connection, “Miles From Nowhere” and “On the Road to Find Out” suggest that the search for meaning is a journey ultimately taken alone. “Where Do the Children Play?”is a song about how technology distracts us from the things that really matter. It sounds absurd when you remember it was written over 50 years ago, but the simple beauty of the melody convinces you that Stevens may have had a point. And then there’s “Trouble,” initially a deep cut from Mona Bone Jakon, which after its use in Harold and Maude became a kind of alt-folk standard.

The soundtrack works as an album because it distills the most important aspects of Stevens’ songwriting to its essence. That it contains fragments of dialogue and incidental music from the film only adds to its appeal. Once you’ve seen the movie a few times, you can’t hear these songs without remembering the scenes in which they played, like when Maude asks Harold what kind of flower he wishes to be: He chooses the daisy because “they’re all alike” and she reminds him that each of them is unique as the opening strums of “Where Do the Children Play?” enter. The added sound from the film means the LP functions a bit like one of those pre-video ’70s LPs that allowed you to “own” a version of a movie in audio form.

Stevens was an enormous star during the ascendant singer-songwriter era of the early ’70s, but his decades away from the public eye put him in an unusual position. For a long time, you’d be most likely to encounter his work on an adult contemporary radio station or in the used record bins. But the more his music was identified with Ashby’s film, the more it became a body of work worthy of rediscovery.

In the movie, “Trouble” is heard near the end, after Harold’s world has been shattered. It was always a great song, but its use in the film gave it an extra layer of resonance. In the ’90s, two artists of the generation that rediscovered Harold and Maude heard something special in “Trouble.” Elliott Smith’s cover landed on the soundtrack to Mike Mills’ Thumbsucker, and Kristin Hersh’s spellbinding take landed on her 2001 album Sunny Border Blue. You can hear in those versions what the movie and Stevens’ music—they exist as one, really—meant to those who found it later, when they needed to hear gently earnest music about fundamental human emotions.

0 comments:

Post a Comment