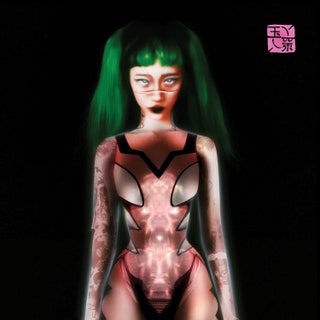

The pioneering second album from the London-based avant-pop artist is a darkly nuanced look at identity and technology, where personal disasters occur at the same scale as the actual apocalypse.

One so-called Coachella Key NFT gives you and a guest access to the festival for one weekend a year, along with any and all virtual productions, forever. It’s a venture in line with artists’ recent investment in virtual reality as a result of the pandemic and companies’ efforts to stake their claim in the prospective riches of the metaverse. Each Coachella token sold for over $40,000, twisting the idea of an event pass intertwined with the holder’s life, death, and the in-between of virtual existence into techno-capitalist grotesquerie. Less interested in remedying the problems of the world we live in, we’re squeezing every drop of its resources to build a new one with the same failing structures, where we can escape to attend a concert in Fortnite or Minecraft while it withers.

In this sense, yeule is a kind of escape artist. The music of the London-based, Singapore-raised artist born Nat Ćmiel addresses how the promising idea of digital life can be just as stifling as real life. On their 2019 debut, Serotonin II, their songs billowed out of synth lines that droned like faraway planes, their beauty so complete that you could miss the terror of their own mind creeping in. Like Enya or Grimes circa Visions, yeule tested the power of a disembodied voice to both spook and seduce, singing alongside interludes that sounded like a hovering UFO or wind sweeping over nothingness. Every now and then the same beat resurfaced to remind you of their capability as a pop artist as opposed to just the creator of whispery and ambient digicore experiments. Its hypnotic, steady pulse distracted you from the fact that they sang about wanting to die.

That overactive death drive persists on yeule’s second album, Glitch Princess, elevating relationship troubles into Shakespearean psycho-dramas backed by soundscapes massive enough to contain them. Layers of limping synths compete with pitched-up vocals that evoke a time that sounds like a technological cataclysm. They’ve mastered the language of self-erasure they practiced on Serotonin II, where bits of narrative implied “micro-deaths,” like a screen shutting off or spending a few hours anesthetized on drugs. Annihilation is a more desperate and unambiguous goal now: yeule details a physical desire to “burn out” of their body on “Eyes,” imagines themself hit by a train on “Friendly Machine,” and throughout the record considers being totally subsumed into someone else. They project their pain onto the vastness of cyberspace as if seeking advice from an oracle and listen back to the static of its reply, hopeful it can illuminate why life is so hard to live.

Despite all their references to wanting to be gone from the world, yeule the person is very present on Glitch Princess. The title of the opening track erases the line between their stage name, taken from the Final Fantasy video game series, and their given name: “My Name is Nat Ćmiel.” With their voice wavering like an A.I. attempting speech, they state their age (22) and a list of things they like: “I like pretty textures in sound, I like the way some music makes me feel, I like making up my own worlds.” A slow synthetic melody plays behind their words, hesitant and twinkling, as if to soundtrack a character that’s just coming to life. But even after presenting their most essential traits, yeule shows that merely knowing your own name is not necessarily enough to tether you to reality.

Press materials for Glitch Princess describe yeule as a cyborg. Though that idea isn’t explicit in the lyrics, it’s present in the way they fashion themself as if they’re not fully autonomous, as if their identity is the responsibility of some external creator. “Always want but never need/I don’t have an identity I can feed,” they sing on “Friendly Machine.” To begin to understand what’s going on inside their mind, yeule treats their existence as something veritably strange. They rhyme “amphetamine,” a stimulant, with “amitriptyline,” an antidepressant, curious about the ways we can manipulate our bodies though we’ll never be able to fully control them. Modern medicine is full of “couplings between organism and machine” wrote Donna Haraway in her 1985 essay “A Cyborg Manifesto,” a challenge for feminism to move away from the rigidity of identity politics. That sense of otherness is central to Yeule’s conception of cyborg-hood; it provides them access to their most core sense of humanity.

On “Bites on My Neck” they sing: “I had to walk into the fire to know how to feel,” simultaneously invoking a resurrection through pain and the flame-licked birth of Frankenstein’s monster. By holding themself at a remove from the rest of humanity, yeule seems to explore basic experiences as if for the first time. “Electric” considers the touch of another as a rapturous event. The song cracks open with an inhuman wail that recalls the esoteric birdsong on Björk’s Utopia—a hook whose strangeness magnifies the song’s wide-eyed, pleading admission that “you’re the only one who knows me.” It’s the voice of a being whose suffering and salvation feel beyond their control—a perspective at odds with other musical cyborgs, like Holly Herndon or Charli XCX, whose art addresses the ways that technology can expand notions of empathy, community, and pleasure.

They give themself a short reprieve from despair on “Don’t Be So Hard on Your Own Beauty,” an emo-leaning acoustic confession that arrives like a solar flare at the album’s midpoint. The song opens in media res: “Currently,” they sing in a sharp coo, “the sullen look on your face tells me you see something in me more pure than this dirty.” The strumming guitar keeps pace with yeule’s tumbling stream of lyrics, as if slowing down might extinguish this rare good feeling. Their words are tinged with hope but are still no rebuke to the self-hatred that saturates the record; the moment they step away from the person they’re singing to, yeule returns to their own “tainted flesh.”

Personal disaster occurs at the same scale as actual apocalypse on Glitch Princess. Where yeule once favored synthetic harp swells and breathy vocal harmonies, there’s now industrial booms, throbbing audio feedback, and synths like thousands of bottle rockets whistling off into the sky at once. The enormity of the sounds make mundane actions—bleeding, eating, having sex—feel precipitous. yeule sings about leaving their “real” body, suggesting there’s somewhere else for consciousness to go. Maybe there will be soon, and we’ll indeed have to re-learn those essential behaviors as if from the beginning. For all their pessimism, yeule offers one consolation: When contemplating the body’s destruction, needs that might have otherwise been hidden can unselfconsciously emerge, like to be seen or known or loved completely.

0 comments:

Post a Comment