Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the 1981 debut from the mysterious Los Angeles post-punk band, who developed a cult following and vanished just as quickly.

Before Su disappeared, she was an extraterrestrial in her city. This was Los Angeles in the ’80s: the cokey, sad, grayscale Los Angeles where what you did was go to porno theaters and go to gigs on the Strip to listen to hair metal. This was also the era of Los Angeles that Bret Easton Ellis wrote Less Than Zero, where the vibe was disaffected and rich kids took joy rides in their parents’ cars to pick up drugs. This era, the primordial ’80s in LA, was tinged with that flavor of pleasant numbness, of swerving under the influence, putting on Mötley Crüe and tuning out. But it was also an era of punk rock coming alive. It birthed Su Tissue and the Suburban Lawns. And in 1981, they released a self-titled LP that felt awake. Suburban Lawns presented an alternate reality where you join a cult and light cars on fire, where you dress up like a Manson girl and obliterate your brain on post-punk.

For a small, mighty, and disaffected sect, the Los Angeles of the early-’80s was all about rebelling against any notion that the city was a generic backdrop, a place to reinvent yourself into another pretty face. X, Circle Jerks, and Fear were writing nihilistic, disaffected punk rock. It was the era of Madame Wong’s, a Chinese restaurant that also featured performances from local punk bands and the short-lived Jett’s. Somewhere in between lay the Suburban Lawns: They weren’t really a punk band, nor were they really a new wave band. Most of their songs were a minute and a half long and not particularly compositionally complicated. And when it came to Los Angeles, they wrote about it from the margins, freeways, and from a deep anger towards the superficial quality of Hollywood. They wrote about West Coast disaffection not from the vantage point of punk rock but from something more feral and strange. They were post-punk Vivian Girls.

They weren’t so into revealing too much about their true identities. The cold hard facts are sparse. They were probably art school kids. They all had stage names: Frankie Ennui, Vex Billingsgate, Chuck Roast, John McBurney, Su Tissue. Su and Vex lived together in an old corner store in Long Beach where the band also practiced. At first, they released their own music and put on their own shows; this was 1979 or 1980 and people weren’t really doing that quite yet. The band self-released an EP called Gidget Goes to Hell in 1979, and a young, newly famous director named Jonathan Demme found out about it and made them a music video that involves a girl in a pink bikini trying to have some fun at the beach and ends up getting eaten by a shark. It ended up airing on Saturday Night Live, and the band went from being DIY freaks who booked their own shows to being beloved freaks who regularly drew crowds on the Los Angeles club circuit. They were no longer semi-anonymous Long Beach guerillas who trekked into Los Angeles for the occasional gig, they were a band on TV.

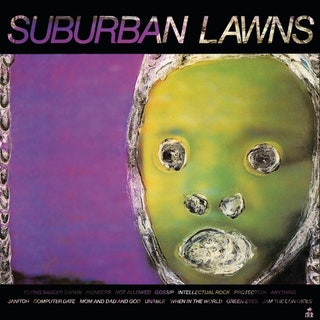

Around this time, they began working on their first and only record, which would eventually be released by IRS, the same label as the Go-Go’s and R.E.M. They recorded at Paramount Studios late at night, on the cheap, with producer EJ Emmons, whose goal was to faithfully translate the energy of Suburban Lawns as a live band on tape. The songs they recorded in those sessions became Suburban Lawns, a devious cocktail of surf rock, post-punk, and new wave. The best songs are the ones Su sings on, like “Gossip,” which glows green like vaseline glass as she sings and chants at the low end of her register, like a sleepwalker. “Lies/Paradox/A parade of rest,” she sings as a guitar cuts through the song like a rusty steak knife. Or “Flying Saucer Safari,” where the band sounds like they’re all wearing tinfoil hats and contacting each other purely via ESP.

And then there’s “Janitor,” the band’s closest thing to a pop song, their biggest hit. There’s a video of Su performing it, one of the very few videos of the band that exist on the web. In the grainy and distorted video, Su wears a baby yellow button-up and a high-waisted plaid skirt. She stands there, not dancing, not interacting with the band, not smiling. She looks bored. She looks like a Dickensian street urchin, or the Orphan from the movie Orphan. “All action is reaction/Expansion, contraction/Man the manipulator,” she sings, looking at the microphone. “Underwater/Does it matter/Antimatter/Nuclear reactor/Boom boom boom boom.” Her voice ricochets, gets louder, and inflates with imaginary helium.

The success of the video as a strange post-punk ur text is largely because of Su and the way she moved. In the video, she sings like she’s in a trance, her brows furrowed, pivoting her body slightly, but more or less staying in the exact place. In one moment, a guitar solo erupts and Su stares at her feet. Like she wants to be anywhere else in the world, like she’s deliberately trying to fuck with you. It’s almost disturbing, vaguely satanic, the stuff of cults.

Her instrument was the kind of voice that you might call “disturbing” or “jarring ” or “difficult.” She was hypnotic in the way that Nico was hypnotic, she had an icy gaze, she looked permanently plagued with ennui. She was Kim Gordon and Kate Bush, Joanna Newsom in a surf punk band, or Haley Fohr from Circuit des Yeux if she could jackhammer her way from her rich, warm alto to a terrifying devil shriek. That’s what Su’s voice did: bungee itself from the low and meaty to the high-pitched and deranged. That’s what made Suburban Lawns tick the Geiger counter of the punk and new wave scene of Los Angeles circa 1981: Su’s voice. Without it, they’d have sounded kind of like Devo.

After all, there isn’t much to a Suburban Lawns song. On a surface level, they wrote straightforward post-punk tracks. Take “Anything”: fast and loud, just under two minutes long, all choppy guitars that occasionally venture off into frenetic solos. What elevates the song is the humor of her paranoid delivery, and Su’s soprano yodel. “Don’t blame it on me!” she sings alongside her bandmates. “If you want it good, get it!” When Su sings, she sounds like her mind is racing, like she has a story to tell you in extreme detail.

As the band gained momentum, writers began to comment on Su, specifically her stage presence, in increasingly comical and confused ways. “While her voice goes to Mars, her lanky, childlike body is in its own private Idaho,” wrote one critic after seeing the band play at the Starwood punk club. “That strange unfashionably dressed girl sang like others slip into the first stage of an epileptic fit,” wrote another. “As hard as it may be to believe, I think she’s really ‘like that,’” opined a writer for the LA Weekly. “In other, less tolerant societies, she would be dismissed as a ‘wacko’ or burned at the stake as a witch.” Here was this woman dressed like Miss Trunchbull from the book Matilda who looked so bored and uncomfortable standing on stage with all of these boys that looked like they were having so much fun. What do you do with a woman who doesn’t meet your expectations? How do you enjoy music when you have a frontwoman who basically wants to be left alone to yodel and then get off stage?

Very few critics knew what to make of Su. Maybe she did communicate with her bandmates with ESP. Maybe “Flying Saucer Safari,” was autobiographical. Maybe Su was a chick from a Diane Arbus photo or a depraved villainess with a fucked up backstory from a David Lynch movie. In reality, Su was just Su.

In an interview she gave with the Los Angeles Times in 1981, she’s described as being quiet and withdrawn—like she doesn’t want to be there. Within the first few beats, she speaks about how when people singled her out for special attention they “don’t understand what this project is about.” And then quickly goes on to say that she thinks that interviews were “obsolete,” which can be interpreted as Su being punk (which she was) or Su being reluctant about being put on any form of a pedestal.

In reality, it was probably both, and as a result, she maintains an air of unknowable mystery. Later in the interview, when she’s asked to talk about her thoughts on songwriting, she’s even more cryptic. “I just like music. I didn’t even think of people singing words.” Su and the Suburban Lawns treated their music like an art project or an accident. Everything they did was part of a performance of being in a band and being public-facing. Maybe that’s why they burned out so fast. They couldn’t sustain that momentum, literally-go-fuck-yourself level of punk rock anonymity.

The band got bigger, enjoying the kind of cult rock band success that led the freaky miscreants to open for U2 and the Clash. And after the release of Suburban Lawns, they went on to release one more EP for IRS, Baby, where they ditched Emmons as a producer for Richard Mazda, who had produced the Fall and the Fleshtones. It wasn’t nearly as well-received, and the band split up shortly afterwards. Su went to Berklee and released an album of experimental solo piano music called Salon de Musique. She appeared in a bit part in Demme’s 1986 film Something Wild as a pregnant housewife who wears a tiny Uncle Sam hat. After that, like cult bedroom artist Connie Converse before her, she completely disappeared.

What happened to Su Tissue is a question that is difficult to answer. In a 2019 article for The Outline, Scott Beauchamp reported on rumors of her being a housewife, a lawyer, or a piano teacher. Spend any amount of time searching the internet for Su Tissue and you’ll find all sorts of bizarre, fetishistic tributes to her, like covers and albums and a super slowed-down video of “Janitor” that sounds like an airport terminal. There’s a whole universe of content about Su Tissue as muse, as an untouchable, unknowable cool girl. Suburban Lawns are a band whose mystery is intrinsic to their identity. So much is left unsaid, and in that empty space, the band lives on.

0 comments:

Post a Comment