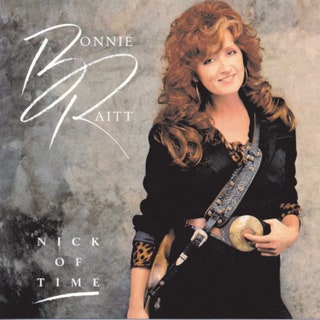

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit Bonnie Raitt’s 1989 blockbuster comeback, a genre-fluid album about love, disappointment, and aging.

In 1983, Bonnie Raitt’s career was at a crossroads. The day after she’d finished mastering her ninth album, Tongue & Groove, the fire-haired Radcliffe dropout and beloved country-blues singer received a letter informing her she’d been dropped from her label. Warner Bros. had signed Raitt in 1971, when she was just 21, and put out eight of her records. But none had been much of a commercial success, and it was time to cut the budget.

Raitt was contractually entangled with Warner for three more years, after which they forced her to put out Tongue & Groove anyway; it was released and largely ignored as was Nine Lives in 1986. She was in her late 30s, recovering from the painful end of a four-year relationship, and suddenly tasked with rehabilitating a music career that should have been in its prime. Years of life on the road had taken its toll, too. As an 18-year-old college student, Raitt met the Boston promoter Dick Waterman, and she got to know the ’70s blues circuit in part by dispensing booze backstage for the likes of Fred McDowell and Son House. When she started recording and touring herself, she earned a reputation as a late-night party girl. “I wanted to be the female version of Muddy Waters or [McDowell],” she said in 1990. “There was a romance about drinking and doing blues.” By 1975 she’d moved to L.A. and started practicing what might qualify as that decade’s version of “Cali sober”—cutting out bourbon to merely drink tequila and wine—and described her drug use as “nothing much: a toot ’n’ a toke.”

But as she neared 40—and considered the possibility of appearing in music videos alongside Prince, with whom she’d recorded a few songs—Raitt decided she’d probably drank enough boys under the table to last her career. She’d grown to hate the feeling of waking up and not being able to remember what she’d talked about with people the night before. She had also put on some weight and was increasingly self-conscious about her appearance. “I remember being so proud thinking I was the last girl singer still drinking,” she told Playboy soon after. “Then I looked in the mirror.” At a show in Louisiana around that time, a fan in the front row passed her what has to be one of the most audacious notes in the history of live shows: “What happened? You got fat. Maybe you should work out or something.”

By 1987, Raitt had quit drinking. She began exercising regularly and attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. She was working on getting her life back on track, but it was a slow reboot. Over the course of the next year, 14 labels passed on signing her; in 1988, Capitol finally offered a $150,000 deal, a package typically reserved for newer artists. “There was nobody interested in signing Bonnie Raitt,” Tim Devine, her A&R at Capitol, told Billboard in 2019. “When I went to sign her, my boss at the time said, ‘Over my dead body.’”

Nick of Time—Raitt’s tenth studio album and first with Capitol—is understandably considered her triumphant comeback. But Raitt herself has often pointed out that there was nothing for her to even come back from: She’d never had a hit record before. For almost 20 years, Raitt had made her career on the road, where she could show off her under-recorded, formidable slide guitar skills and easily compensate for lagging record sales at the box office. “I never pretended to be a great artist or a great originator,” she once said. “I’m just an interpreter of good music.”

The closest she’d come to mainstream success was a 1977 cover of Del Shannon’s “Runaway,” which has her snarling and sliding around a Norton Buffalo harmonica break. It was a big leap from “Mighty Tight Woman” and “Women Be Wise,” the sweet but almost painfully innocent sounding Sippie Wallace covers on Raitt’s 1971 self-titled album. Raitt hit her stride as an interpreter and recording artist when her voice earned some attitude and grit in addition to its innate emotional clarity, and when she began to transform songs written by men (“Runaway,” “Too Long at the Fair,” and “Angel From Montgomery,” to name a few) with her simple shift in perspective. But she still wasn’t really on the radio.

Who would’ve guessed Nick of Time—a genre-fluid album about love, disappointment, and aging—would be Raitt’s turning point? Certainly not the people who made it. Raitt, 39, was emerging from what she called “a complete emotional, physical and spiritual breakdown,” and producer Don Was (of Was (Not Was)), was at “rock bottom” in his production career. He’d only crossed paths with Raitt by chance, at an L.A. studio in 1986, because he’d lost his client’s tapes in the back of a taxi on his way out to California and had to push their session by a day. Soon after, Raitt teamed up with Was to record “Baby Mine,” a song from the animated 1941 Dumbo movie for an album of reimagined Disney songs, and they knew they wanted to continue working together. It wasn’t an easy sell. “If it comes down to it and a record company comes along and insists that she have a real producer,” Raitt’s managers told Was over lunch one day, “we’re going to throw you under the bus.”

But Capitol’s low investment in the project also came with the hands-off blessing of low expectations, and in 1988, Raitt and Was took some stripped-down demos into a week-long session at Hollywood’s Ocean Way Recording. For once, Raitt felt no pressure to emerge with radio-ready hits; she and Was just wanted to make songs they would be proud of. For his part, Was knew the key to production would be staying out of the way: “It was just about hearing her unadorned voice,” he told Billboard. “Everything else would augment that.” They cut about two tracks a day, using as few instruments as they could and aiming for a sound that felt, in Raitt’s words, “as live and uncorrected as possible.”

Raitt’s slide guitar appears on about half of Nick of Time, a unifying thread in an album that jumps from country to pop and R&B. For much of the ’80s, Raitt had been touring with a limited budget, playing full sets with only a bass player to accompany her guitar. As her playing, and reputation for it, had improved, she’d realized it was what set her apart as an artist. “It was time to showcase the things about me that were different,” she told the Boston Globe in 1989. “There are a lot of female hormones in that slide playing.” (John Jorgenson, who played guitar on “Too Soon to Tell,” credits Raitt’s playing on Nick of Time with a general slide revival in country music in the ’90s.)

Raitt, never known for her songwriting, bookended the album with an unusual ode to aging, “Nick of Time,” and a closing manifesto, “The Road’s My Middle Name.” She personally begged the Bay Area singer-songwriter Bonnie Hayes to give her both the torch song “Love Letter” and the heartbreaker “Have a Heart.” According to Hayes, the latter was written as a reggae track for Huey Lewis, and it is difficult to imagine him delivering the iconic opening line—“Hey… shut up!”—with the same playful bite that Raitt gave it. The song peaked at No. 3 on the adult contemporary chart, Nick of Time’s biggest hit.

Raitt’s career might have been adrift, but she had plenty of loyal friends to call on. “Cry on My Shoulder,” doused in ’90s schmaltz, casually features backup vocals by David Crosby and Graham Nash, and Herbie Hancock accompanies Raitt on the aching ballad “I Ain’t Gonna Let You Break My Heart Again.” Among others, “Too Soon to Tell”—which Raitt has called the only true country song she ever made—has Was (Not Was)’s Sweet Pea Atkinson and Sir Harry Bowens chipping in on backup vocals. (Mike Reid, who co-wrote the track, would go on to co-write “I Can’t Make You Love Me,” one of the biggest songs of Raitt’s career.) The lead single was a cover of Jon Hiatt’s “Thing Called Love,” and with a shrewd eye toward VH1 airtime, Raitt cast her friend Dennis Quaid as a flirty himbo in the accompanying music video.

Nick of Time was released on March 21, 1989; it hit the label’s sales goal in a week and then, to everyone’s surprise, continued to sell steadily. The real boost came after the 1990 Grammys, when Raitt—unsigned and bottomed-out just a few years prior—won all four awards she’d been nominated for, including Album of the Year. “I’d just like to thank Bonnie Raitt,” Was said onstage, next to his disbelieving partner, “for setting an example here. If you maintain your integrity, never underestimate your audience, and just try to make a good record, people will respond to you.” A few weeks later, Nick of Time was the No. 1 album in America.

Raitt has likened this post-Grammy rise to a “hyperspace”—it was the moment everything changed for her. But why the hell did it take this long to happen? Nick of Time coheres around a clear and earnest philosophy that no doubt registered with the second-wave feminist boomers who went out and bought it in droves: These are songs performed by a woman who’d reached a personal and professional nadir and pulled herself out. And she did it all, as the New York Times review put it, at a “certain age.” Thirty-plus years after its release, the album’s point of view—a woman who feels liberated by her age and life experience rather than limited by it—is still refreshingly out of the ordinary. It’s the story of Raitt attempting to come to terms with her adult self. “I can handle the things about myself that I didn’t like before,” Raitt told the Globe at the time, just a few months shy of turning 40. “I don’t feel that anything is leading me around anymore—love, or the road, or my career. I feel like I’m in control of my life. I have a real spirit of purpose.”

Nick of Time exceeded everyone’s expectations; it didn’t only sell over 5 million copies, it wholly revitalized Raitt’s career. Her subsequent release, 1991’s Luck of the Draw, surpassed it in sales and cemented her as a ’90s powerhouse with hits like “Something to Talk About” and “I Can’t Make You Love Me.” Still, for an artist so defined by interpretations, it’s Raitt’s own “Nick of Time” that stands out from the pack now. Raitt wrote it when she was playing around with a Drumatix synth with built-in sounds, looking for something that had a Philly Soul vibe. After she played the demo in the studio, Was layered in an old synth, and drummer Ricky Fataar got creative: “He put a sandbag on his belly and mic’d it,” Raitt told USA Today in 2014. “Then he played that signature heartbeat sound [on it] that made it intimate.” In the first verse, Raitt sings of a friend who “sees babies everywhere she goes” and “wants one of her own” but has an indecisive partner; in the second, she speaks to the strange sadness that accompanies parents and children seeing one another age. Her voice is unusually gentle and plaintive: “When did the choices get so hard, with so much more at stake?” she wonders on the bridge: “Life gets mighty precious when there’s less of it to waste.”

The ’90s were a less forgiving time, but the existential angst of a woman in their mid- to late-30s remains. In an industry that perennially favors the young, that was and remains racked with ageism and sexism, Nick of Time feels startling simply for existing as it was made, a contentedly unresolved document about a grown woman losing and then reestablishing herself at a life stage when her story could have easily joined so many others in the ether.

It’s bittersweet to know that “Nick of Time” played a part in pushing Raitt’s friend’s partner to make a decision: Not long after the album came out, the couple got married and had a kid. (According to Raitt, they nearly named him “Nick.”) Still, it’s nice to know that the song itself ends on what is more or less a white-knight fiction. In the final verse, Raitt sings of redemptive love, someone who “opened up my heart again” and gave her “love in the nick of time.” Raitt was newly signed, sober, and recentered, but she was still single and recovering from heartbreak. She had a lot more life to live.

0 comments:

Post a Comment