Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit Spacehog’s 1995 debut, an architecturally sound, occasionally great, always amusing collection of transatlantic power pop.

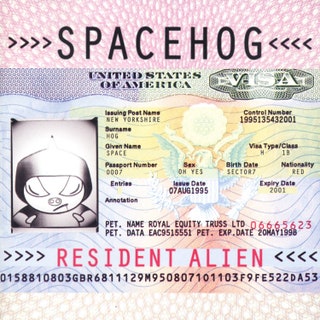

Spacehog was founded in New York City in 1994 when guitarist Antony Langdon met drummer Jonny Cragg in an East Village café where Cragg had a job killing rats with a shovel. This is the story that Cragg seems to have told every reporter he’s ever spoken to, so it may as well be true. They recruited Langdon’s younger brother Royston, a singer and bassist with a notebook full of songs left over from a previous musical endeavor, and then Cragg’s friend Richard Steel on lead guitar. All four band members had come to the States from Leeds, England. They named their first album Resident Alien in reference to their visa statuses.

They could’ve joined up back home and saved themselves a trip, but there was probably some calculation behind the move. In the UK, Britpop had taken hold and you couldn’t swing a Super Furry Animal without hitting a band turning its retro influences into brightly catchy alternative rock. But in New York, hip-hop reigned and the local A&R departments had to fly all the way to Seattle to find guitar groups, which meant Spacehog had Lower East Side clubs more or less to themselves while they played nightly auditions in the industry’s backyard.

British bands were a tough sell in the U.S. but Spacehog made a commercially plausible pitch that distinguished them, somewhat, from their countrymen: They were the happy middle between Britpop and American grunge, with the hooks and humor of the former tempered by the familiar Big Muff’d power chords of the latter. (Plus, if you liked the Gallagher brothers, just wait till you got a load of the Langdons, who were equally quarrelsome but slightly more handsome.)

Spacehog’s own retro influences primarily included British glam-rock artists of the ’70s—Bowie, Queen, T. Rex, Slade—to whom they paid tribute through high-effort, decorum-free stagecraft. In concert, the Langdons dressed like Spiders From Mars and prowled around like a pair of Freddie Mercurys; Steel played solos with a foot up on his monitor and a cigarette stuck in the headstock of his Flying V; and Cragg twirled drumsticks and lit his gong on fire. All this would’ve looked pretty stupid if their music couldn’t back it up, but it actually sort of could—one song in particular!

If you remember Spacehog, it’s almost certainly for their first single “In the Meantime,” an alt-rock anomaly so packed with wonders that it seems to give you a new reason to like it every time you listen. There’s the dial-tone intro (sampled from a track by the Penguin Cafe Orchestra); Royston’s yodeling falsetto and venturesome bassline (how he played it while singing is a mystery that has vexed other singing bassists for 26 years); the double-bend guitar riff; the dramatically dopey lyrics of the verse (“And in the end we shall achieve in time the thing they called divine”); the fuzz-bomb chorus sung from the perspective of friendly extraterrestrials (“All in all we’re just like you/We love the all of you”); and the bridge that flies by like an F-14. It’s not seamless, but that’s by design; the song’s three main sections are all in different keys, which creates the feeling, harmonically speaking, of climbing an Escher staircase where the rules of gravity change at every landing.

“‘In the Meantime’ was the first song I ever played in Spacehog,” Cragg has said. “It had this brilliant rubbery McCartney-esque bassline, played by this little kid with a huge voice… It was the one that got me hooked and made me realize what a special talent Royston Langdon is.” The band recorded a demo in a Manhattan jingle studio, inviting Antony’s friend Sean Lennon to tag along. (Afterward, “he invited us back to the Dakota building to jam,” Cragg remembers. “Sean gave Roy one of his dad’s Rickenbacker 4001 basses that night.” He played it on the album version of the track.)

In 1994, record labels were so desperate to land the next Nirvana that one of them had even signed Candlebox. So after Spacehog's demo made the rounds—quiet verses and loud chorus? Check and check—a live showcase was arranged for Sire founder Seymour Stein, who offered them a deal immediately. Resident Alien was released in October 1995 and sold 500,000 copies in its first eight months, largely thanks to its lead single, which played on MTV and topped Billboard’s mainstream rock chart for four weeks. Spacehog opened for Tripping Daisy and Everclear and then hit the road with the Red Hot Chili Peppers. When they got home, they packed New York’s medium-size venues by themselves.

They weren’t exactly rock stars, but in a scene that wouldn’t beget the Strokes for a few more years, the Langdons became local celebrities. Soon, they were recurring characters in international tabloids that were cool on the music but captivated by the brothers’ romantic adventures. Here’s the short version: Antony befriended fledgling heartthrob Joaquin Phoenix, who introduced the Langdons to his then-girlfriend actress Liv Tyler, who broke up with Phoenix and began dating Royston—they eventually married and divorced—and then introduced her friend Kate Moss to Antony, who unsuccessfully proposed marriage to the model after just three months. (Phoenix and the Langdons stayed friends; he cast Antony as his personal assistant in the 2010 mockumentary I’m Still Here.) There weren’t any blogs or camera phones around to document it, so we’ll never know for sure, but it’s possible that everything that happened to all the bands in Lizzy Goodman’s New York aughts-rock oral history Meet Me in the Bathroom happened to Spacehog first between 1995 and 2001.

One thing that didn’t happen, though, was another hit. Follow-up singles from Resident Alien failed to connect, and Spacehog’s artier second record, 1998’s The Chinese Album, generated nice reviews but not much business; Sire gave it a small push and then dropped the band. Comeback attempts in 2001 (The Hogyssey) and 2013 (As It Is on Earth) stalled, and they split up for good in 2014, leaving behind one song for future generations of karaoke singers but perhaps failing to, in the end, achieve the thing they called divine.

Still, “In the Meantime” seems to be remembered more fondly than other one-off hits from its decade. The song’s bassline was recently voted the fourteenth best of the whole 1990s by readers of UltimateGuitar.com (just four spots behind the Seinfeld theme). This summer, Ezra Koenig revealed a soft spot for the track on an episode of his Apple Music show Time Crisis, imagining a Yesterday-style scenario in which he wakes up in an alternate timeline where nobody else remembers Spacehog, allowing him to steal “Meantime” for the next Vampire Weekend album. (“I could make this work in 2021”, he said.) Were Spacehog not merely a one-hit wonder but in fact, as has been posited, the greatest one-hit wonder?

Revisiting Resident Alien now, it’s easy to hear the ingredients for a longer career than they had. Many alt-rock debuts had one catchy single and a dozen lesser songs bearing little resemblance—that was a good enough blueprint for some other Brits—but Resident Alien over-delivers. Considering the pressure a track like “In the Meantime” would put on any band’s first record (especially when sequenced as the album’s opener), Spacehog’s is an architecturally sound, occasionally great, always amusing collection of transatlantic power pop.

Recording the band in a Woodstock, New York studio, producer Bryce Goggins (Pavement, Apples in Stereo) mines the tension between their native influences and the American rock of the time and winds up with something that never sounds fully like either. The guitars—thick and wooly but with top-end bite, deployed in wide dynamic range and played into warm amps through long chains of fuzz and phaser pedals—clobber those on most early Britpop records. But there are also pianos, glockenspiels, and bongos, among other textures not found on many grunge albums, not even when Stone Temple Pilots mounted their own glam revival a year later.

It might be harder than you’d think to pick a second-favorite song on Resident Alien, because Spacehog had a way with a tune. Take “Cruel to Be Kind” (no relation to the Nick Lowe song), a rewrite of “Jessie’s Girl” so likable that Rick Springfield may as well just give them the publishing. Or “Space Is the Place” (no relation to the Sun Ra song), a Buzzcocks-style pop-punk workout that gets stuck in your head in a lot less time than it would take to parse its sexual politics (“Just because you kissed your brother/It doesn’t mean to say you’re gay/’Cause even when you’re fucking him it doesn’t mean you don't love me”).

If either of those descriptions makes this album sound derivative, well, it is, but Spacehog were not worried about camouflaging their inspirations. You can hear the Langdons doing the “hoo hoo”s from “Sympathy for the Devil” in “Never Coming Down - Pt 1” and Royston bellowing the hook from Tin Machine’s “Crack City” through the outro of “Spacehog”—and is the chorus of “Starside” quoting the melody from “Starman” or the theme from Star Trek or both? A lifetime’s worth of listening to their idols hadn’t yet coalesced into a unique identity, but it’s fun to hear the band figuring it out.

The album’s most shameless lift is conceptual. Lyrically, Resident Alien is an unlicensed reboot of Bowie’s Major Tom franchise starring the Langdons as astronauts floating around heaven feeling low. Narrators on no fewer than five tracks spend the verses bemoaning their earthly miseries before blasting off to outer space for the choruses (“See you later, now I’m gone/So long I’ll see you when I’m starside,” “Space is the place where I will go when I am all alone and when nobody calls me on the phone,” etc). As a songwriting device, it works better some times than others, but taken as a metaphor for the band’s own feelings of dislocation—they’re aliens, they’re resident aliens, they’re Englishmen in New York—it has some thematic resonance.

Much was made in early reviews over Royston’s vocal similarity to Bowie, but his impersonation on Resident Alien is so over the top that it kind of becomes its own thing, a baritone vibrato with enough wobble to send a less confident Adam’s apple flying across the room. Royston could also jump octaves like Bono and grind vowels like Axl Rose, stirring up drama even in sleepy side-two ballads “Ship Wrecked” (“So if you raise a glass to love you passed/Raise a glass to me”) and “Zeroes,” about a woman who gives him the brush-off when he asks for her phone number. During one of Spacehog’s hiatuses, Royston failed an audition to replace Scott Weiland as the singer of Velvet Revolver—their loss.

In recent interviews, members of Spacehog have reflected on what they might have done differently to prolong the band’s lifespan. (“I think the prevalent feeling amongst the group is that we fell short of our potential,” Cragg lamented in 2017.) Antony has said he wishes they’d built momentum by releasing a couple of other singles before “In the Meantime,” which wouldn’t have hurt. Were they also hindered by an awkward name? It could’ve been worse: “I believe Grass was the original idea,” Cragg has said, “but it was shite” (and might’ve invited unfair comparisons when they shared a bill with Supergrass). “We settled on Spacehog in the end. I think it was a bit less shite.” Maybe they miscalculated the demand for a Ziggy Stardust update at a time when American glam rock had only just been vanquished, and when David Bowie himself was making some of the least-loved music of his career. “We were inauthentic,” Cragg has said. “We got thrown in with all that mid-’90s alternative rock… but we really didn’t have all that much in common with a lot of the other bands out there.”

Others blame Spacehog’s followup to Resident Alien, The Chinese Album, a concept record with a concept that nobody could ever quite figure out. It was supposedly intended to be the soundtrack to a movie that was never made—R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe was said to have toyed with directing it—about a band that moved to Hong Kong after being dropped by its American record label, but none of that is clear in the music. The songs themselves were actually pretty good, though. Try “Mungo City,” “Carry On,” and “Almond Kisses,” featuring Stipe.

Then again, in the second half of the ’90s, right around when Spacehog might’ve had their theoretical second hit, the six major record labels became five; the radio industry was deregulated and playlists tightened; MTV abandoned music videos; and at-home broadband gave rise to file-sharing—not exactly conditions under which a band of arch, glam-rocking aliens were designed to thrive. So maybe Spacehog peaked too early. Or maybe they wrote a great song and came 3,000 miles to play it for us just in time.

%20Music%20Album%20Reviews.webp)

0 comments:

Post a Comment