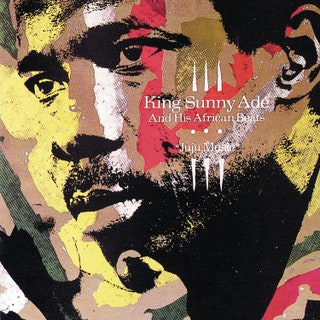

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit Nigerian superstar King Sunny Adé’s 1982 international breakthrough, an album whose complex fusion of musical traditions produced a singularly captivating groove.

African music has been part of America’s cultural DNA since roughly 1619. But in 1982—the year Michael Jackson’s seismic “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” interpolated “Soul Makossa,” the unlikely 1972 global hit by Cameroon’s Manu Dibango—actual African music LPs were thin on U.S. ground. Cratediggers might’ve found the Soul Makossa LP, or albums by South African cultural emissaries Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela; perhaps they lucked upon Fela Kuti’s magnificently excoriating Zombie, issued by Mercury in 1977 in a failed attempt to break the artist stateside. Otherwise, the sounds on offer were less pop than ethnographic: field recordings on the Folkways and Nonesuch Explorer labels, or the handsome one-off Missa Luba LP, an independence-era snapshot of a Congolese boys choir that became a favorite among ’60s hi-fi aficionados—as did Babatunde Olatunji’s Drums of Passion, the percussion-driven firestorm that functioned as a home-study course for the Velvet Underground’s Moe Tucker, who played along to it in her suburban Long Island bedroom.

This was the backdrop—pre-internet, pre-Graceland—for King Sunny Adé’s Juju Music, a masterpiece of sublime dance music and chill-out grooves that rang the opening bell for the fruitful-if-problematic “world music” marketplace, with Adé leading a vanguard of artists who would introduce a wealth of new sounds and conversations into the American pop biosphere. Juju Music was even a relative commercial success, spending 29 weeks in the bottom half of the Billboard 200, remarkable for a record sung mainly in Yorùbá. Its creative triumph was self-evident: a radiant vortex of melodic ouroboros rhythms, dubby yet dazzling, its gentle flow so irresistible that the chiming first chords of “Ja Funmi,” the dance-trigger lead track, remains for many a musculoskeletal call-to-prayer—what, say, the paired four-note opening of “Dark Star” is for Deadheads.

West African highlife, soukous, Afrobeat, and jùjú were hardly news to local fans, expat communities, or anyone else with access to the music. (Tastemaking British DJ John Peel shopped for African LPs at Stern’s, London’s legendary music import shop, and began playing Adé’s records on his BBC Radio 1 show in the ’70s.) These styles were ongoing dialogues with the (African) American music marketed in Africa, be it rock, blues, jazz, R&B, or country, so the echoes were no accident. Sunday Adeniyi Adegeye, the son of a church organist who left high school to earn money as a drummer, was an avid listener of U.S. soul and country who started his first group, the Green Spot Band, at age 20 in 1966. Like many artists at the time, he took up the electric guitar, and by the mid-’70s, he was self-releasing modern jùjú records on his own Sunny Alade label and distributing them with Decca. When he signed with Island, he was already a wealthy, established Nigerian bandleader, with a mature fanbase buoyed by the country’s oil boom and an elegant, cosmopolitan style—a Yorùbá Philly Soul to the roughneck Afrobeat James Brown of his countryman, Fela. The sound seemed a perfect candidate for export.

Measured against Island’s ambitions, Juju Music was perhaps a letdown. Having turned reggae in general, and Bob Marley in particular, into global commodities, the label assumed they might do the same with the brilliant pop styles of a whole continent. In fact, Marley money got things started: When producer Martin Meissonier sought funding to record Juju Music, Island sent him to CBS Nigeria to collect royalties from Marley’s recordings. (Legend has it that he was presented with bags of cash.)

Island tested Anglo-American waters in 1981 with Sound D’Afrique, a well-curated compilation of motherland gems released on its subsidiary label Mango, usually home to Jamaican and Caribbean releases. With tracks by Senegal’s Étoile de Dakar (fronted by soon-to-be global star Youssou N’Dour) and Congolese guitar hero Pablo Lubadika Porthos, but no liner notes or photos, the LP didn’t register widely. Still, its cascading guitar lines, chortling horns, and polyrhythmic beat webs—which brightened further on 1982’s follow-up Sound D’Afrique II—were revelatory for many newcomers. DJs at my upstate New York college radio station were immediate converts; the spiraling leads and stop-motion arpeggios were guitar-fiend lingua franca, however removed they were from the blues roots of American funk and rock.

Where the Sound D’Afrique material was cherry-picked for English and American audiences from tracks recorded for the African market, Juju Music was tailored differently. Island had experience retooling regional sounds: The original Wailers recordings produced in Jamaica by Lee “Scratch” Perry (“Small Axe,” “Kaya”) were the aesthetic gold standard, but it was the polished remakes that made Marley an international superstar. Juju Music adopted the playbook used for Catch a Fire, the Wailers’ Island debut: Adé recorded at the well-appointed Studio de la Nouvelle Marche, aka Otodi Studio, in Lomé, Togo, and an Island engineer remixed the tracks in London.

The outcome is a subtle shift in Adé’s sound: tighter, brighter, lusher, and more detailed. His Nigerian releases extend songs to fill entire LP sides, or segue them into long medleys. King Sunny Adé G.M.A., a self-released 1980 set on his Sunny Alade label, presented the original “Ja Funmi” (titled “Ori Mi Ja Fun Mi”) as an 18-minute suite. But at the request of Island’s Chris Blackwell, Juju Music featured individuated tracks, fresh recordings of catalog songs ranging from three to eight minutes long. Tempos were scooched up slightly, mixes more layered and filigreed, while dub effects (by reggae vet Godwin Logie) added extra buoyancy and stoner ambiance.

The change is most noticeable in the beat mix, particularly the Yorùbá talking drums, the heartbeat of jùjú. Where the pitch-shifting instruments pop like firecrackers on King Sunny Adé G.M.A., they’re often dialed back on Juju Music into a more uniform, near-ambient swarm. Jùjú traditionalists already felt that Adé was cluttering up the music with too many elements, and Juju Music—recorded with his ’80s band, the 20-plus-member-strong African Beats—pushed that effect to the hilt: six electric guitars, counting steel and bass; keyboards; and a battery of percussionists and singers. The album splits the difference between clubbing and couch-lock, honoring in its way the cool urban spirit of jùjú, a decades-old style rooted as much in listening music (the acoustic barroom “palm-wine” style of the 1920s) as in drum-driven dance parties.

Another Westernized touch is the spotlight on steel guitarist Demola Adepoju, who gets nearly a minute of soloing on “Ja Funmi,” a display missing from the earlier Nigerian version, which keeps his phrases pithier and gives more room to grouped Yorùbá vocals. Adepoju’s silvery skywriting is an invitation for rock and funk fans to hear electric guitar playing in a different way: more as a weave than as strictly demarcated rhythm and leads.

The vocals function in a similarly textural way, at least for non-Yorùbá speakers, with Adé’s buttery tenor triangulating Curtis Mayfield, Brook Benton, and country crooner Jim Reeves (the latter hugely popular in Nigeria) as he unspools fluid call-and-responses with a half-dozen co-vocalists. Perhaps unsurprisingly for music born in the massive port city of a former British colony, the sound is tinged by the swell of Anglican church choirs, as well as the keen of Koranic recitation. Jùjú was melting-pot music from the get-go (the out-of-print 1985 LP Juju Roots 1930s-1950s is a great primer) which mutated just like blues and old-time American music did when electric guitars landed. But it also became music that expressed Yorùbá identity—its very name adopted, by some etymologies, from a disparaging Western term for traditional African religion (others trace the name to a phonaesthetic word for a characteristic beat).

All this made jùjú, like reggae, a supremely inviting export with myriad cross-cultural access points. Juju Music is an object lesson in fusion, beginning with the mellow, churchy uplift of “Ja Funmi,” its unfurling steel-solo phrases bursting through drum layers near the five-minute mark like sun through clouds. The melody has a flicker of American country music; steel guitar struck Adé as a novel way to echo the traditional licks of African fiddle. On “Eje Nlo Gba Ara Mi,” the steel is like the ornamentation of a Kehinde Wiley portrait, both filigree and melody, trading off with the synthesizer. A similar dynamic propels “Sunny Ti De Ariya,” a talking drum workout with a “What’s Going On”-style backdrop of chattering musicians. On “Ma Jaiye Oni,” which gets a distinct tempo boost from the Nigerian version, steel takes center stage with riffs that sound distinctly Hawaiian—music that seeded early jùjú via 78 rpm discs during the international Hawaiian guitar band craze of the 1920s, the ur-“world music” explosion. (Hawaiian music fed the roots of American country music steel the same way.) Given the likely African origin of what country and blues fans know as slide guitar, it’s a marvelously full-circle moment.

Island must have figured the message in Ade’s songs would do little to sell him abroad, because the LP included no lyric sheet. Translations aren’t widely available, which is unfortunate, since Adé, like most good lyricists, seems to operate on multiple levels, alternately seducing, praying, and philosophizing. “Ja Funmi,” which translates as “Fight for Me,” riffs on proverbial warthogs, baobab trees, and the great blue turaco, but Adé also rues life’s hard knocks and gives himself a fame-related pep talk familiar to any modern hip-hop fan. The medley “365 Is My Number/The Message” ratchets up the tempo on a fragment of one of Adé’s rare English-language songs, the side-long “365 Is My Number – Dial,” a pitch to a reluctant lover from 1978’s Private Line, then veers into a hall-of-mirrors dub workout without losing the groove. Steel runs and sci-fi synth squiggles function like the lowing cows and roaring lions on a Lee Perry session, dancefloor punchlines amid echoing rhythm guitar salvos.

Shortly after Juju Music’s release, I saw Adé make his New York debut at the Savoy, a short-lived rock club in Times Square. A streamlined version of the African Beats—only 18 musicians—kept things lit for over two hours, a small taste of the all-night jams they regularly played back home. Melodic phrases and drum grooves flickered, dropped out, then reappeared in the lead-up to another song; multiple guitars and steel spun against twin talking drums and a percussion battery not so far off from the snakey-sneaky vernacular of American jam bands. Adé sang beautifully; experienced fans lined up to praise him with bills, per tradition, pasting currency to his sweaty brow. Adé grinned with gratitude, and the sold-out crowd (unsurprisingly including David Byrne) shimmied into a single pulsing organism, like bees drunk on honey.

The success and sheer gorgeousness of Juju Music led to a windfall of Nigerian releases in the West, including LPs by Adé’s main jùjú competitor, Chief Commander Ebenezer Obey. More Fela Kuti recordings appeared in the States, as well as compilations from other African scenes; Paul Simon came across one from South Africa, got inspired, and violated the United Nations cultural boycott of the country to record Graceland, which sold roughly 15 million copies worldwide. “World Music” was launched as a marketing concept in a north London pub, creating a pipeline for all sorts of dazzling and vital traditions while simultaneously marginalizing them.

Adé benefitted from all this, but he never became the Bob Marley-caliber star some thought he might. After two more records for Island, 1983’s Synchro System and 1984’s Aura, which were more polished production-wise and less compelling musically, he parted ways with the label and, without abandoning periodic tours and export LPs, settled back into being a homeland hero. He remains royalty: At a 2013 performance for the pan-African media network EbonyLife, Nigerian pop ambassador Wizkid got down prostrate before the King during a cameo with Adé’s band, which sounded as supple and seductive as ever.

While contemporary Afrobeats isn’t averse to spotlighting its roots—Burna Boy’s 2018 song “Koni Baje” is a straight-up jùjú tribute—these days jùjú itself is a throwback, the kind of music your parents like. But its sweetly swarming melodies and rhythmic webs are infused in the genre-blurred pop sound of young Nigeria, where an ever-growing constellation of stars has proved potent enough to attract comers like Justin Bieber and Brent Faiyaz, trailing Drake, Beyoncé, and others who are building bridges that feel more pan-African than colonial. Wizkid has taken a song sung partly in Yorùbá into the Billboard Top 10; indie labels like the Kampala-based Nyege Nyege Tapes are growing scenes on the ground; and Universal and Sony have opened regional offices in West and South Africa to develop the new wave of music internationally. The doors are open wide, and everyone passing through walks in Adé’s footsteps.

0 comments:

Post a Comment