Initially conceived as an orchestral tribute to Iceland’s remote majesty, the Blur and Gorillaz frontman’s second solo album blossoms into a wide-angle commentary on grief, loss, and climate crisis.

For Damon Albarn, the ability to disconnect is vital for creativity. It’s what drew the Blur and Gorillaz frontman to Iceland’s remote wilderness nearly 25 years ago (he wrote “Song 2” on his first visit), and what has kept him returning so frequently that he’s now a dual citizen. The British singer-songwriter and musical polymath is rarely short on inspiration; he’s made more than a dozen albums spanning Britpop, Mali folk, film soundtracks, and opera (next up, he recently said, is a ballet). But in recent years, and especially during lockdown, he’s spent considerable time sitting by his piano at his home near Reykjavik, gazing out the window into the extraordinary countryside.

His sprawling second studio solo album, The Nearer the Fountain, More Pure the Stream Flows, is a tribute to this landscape—a majestic panorama of grassy meadows, black sand beaches, glaciers, and active volcanoes. It’s the sort of otherworldly vista that makes you think big and feel small, and Albarn, now in his fifties and increasingly worried about the climate crisis, has become protective of its quiet, pristine beauty. Using misty, classical atmospheres and melancholy pop melodies that evoke a sense of awe and loss, he presents a love letter to a beloved landscape that he wants to preserve but is already mourning.

Albarn’s initial vision for the record wasn’t quite so sentimental. In 2019, he was commissioned by Lyon’s Fête des Lumières to take on any project of his choosing, and suggested creating an orchestral interpretation of the view outside his living room window. With the help of local Reykjavik musicians, who came over for long improvisation sessions, he began to build an instrumental sketch of the terrain. “Someone would be in charge of the clouds, someone would be in charge of the outline of [Mount] Esja, someone would be on waves, and birds, and golf carts,” he told Reykjavik’s Grapevine. “Once you take it out of the moment and the environment... immediately it becomes very abstract.” When the pandemic shut the sessions down in early 2020, Albarn had to reimagine what the project might become. He enlisted two old friends, Verve guitarist Simon Tong and Gorillaz collaborator Mike Smith, to help turn the recordings into a more song-based, pop-oriented LP.

The final product is loosely based on the pandemic-inspired concept of particles (a lyrical point that Albarn overuses), but it feels larger, like a stream-of-consciousness meditation on earth’s natural forces—extreme weather systems, gravitational pulls, the migratory patterns of birds. They’re rendered in swirls of ambient soundscapes, waltzing lullabies, and stormy, jazzy inflections, and you can hear threads of those early orchestral sessions seeping through. At times, the wide mix of sounds feels erratic, and the instrumentals don’t always work (“Combustion” has dizzying, you-had-to-be-there energy), but perhaps there’s an argument for discomforting friction. Nature is volatile, unpredictable, and clearly in charge.

Albarn is notorious for rejecting fame and protecting his private life (see: Iceland), so it’s surprising that so much of The Nearer the Fountain feels biographical. Drifting from Iranian funeral ceremonies (“Daft Wader”) to Uruguayan architecture (“The Tower of Montevideo”) to the foggy beaches where his daughter grew up (“The Cormorant”), he reminisces about all that is lost with the passage of time. “I now drift, daydreaming, to when we were happy here on this beach,” he sings. “We played with our children and they were happy, too.” Although he has often used his musical projects as travel diaries of sorts, there’s an intimacy to his solo work that we simply don’t get elsewhere. These songs are more like vivid journal entries than faded photographs, with rare glimpses at how he thinks, feels, grieves, and remembers.

There’s another reason for all this existential thinking. In the middle of the recording process, Albarn lost his longtime friend and close collaborator, the legendary drummer Tony Allen, sending Albarn on what he’s called “his own dark journey.” That phrase, along with the album title and opening track, are references to the elegiac poem “Love and Memory,” by the 19th-century English poet John Clare. Albarn’s mother had gifted him an anthology of the writer’s work when he was a teenager. When he rediscovered it during lockdown, it became a companion text for grappling with the magnitude of loss happening all around him.

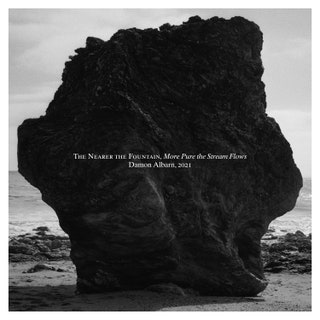

Clare was a champion of the countryside and his own era’s voice of environmental alarm. He regarded mortality and nature as one, death as natural and certain as the seasons. Albarn found solace in this wide-angle thinking, and began considering the human condition as an extension of nature rather than the other way around. The album’s dark cover art—a large rock with a poetic epigraph, the artist’s name, and the year—feels like a visual reference to a gravestone. At first the boulder seems enormous, nearly taking up the whole canvas. But the sea just beyond it, ceaseless and sparkling, has a way of lending everything a new perspective.

The album’s most affecting moments zero in on Albarn’s close relationship with nature, one built on trust and deference. In the wistful piano ballad “The Cormorant,” he describes his daily swims in Devon Bay, off the English coast, and the helplessness he feels being swept up in the ocean’s cold, black currents, which have recently become inhabited by great white sharks. “Tipping goes the cormorant, I think she knows I’m a pathetic intruder into the abyss,” he sings, his melodies dipping and diving as gracefully as a shorebird.

On the deceptively lighthearted “Royal Morning Blue,” he marvels at the way a slight shift in temperature can turn rain into snow and transform an entire landscape, only to disappear. Everything is fleeting, he seems to say. Don’t get too comfortable. When he starts to sing about “the end of the world,” his voice is suddenly slanted and uneasy, as if the day has shifted from a far-off theoretical to a palpable, inconvenient truth.

0 comments:

Post a Comment