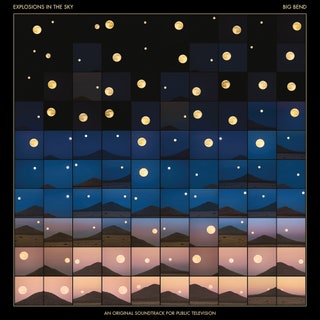

On its first soundtrack in seven years, the Texas band mirrors the subtle landscape and beauty of the national park that the namesake documentary captures.

Sorry, but everything isn’t actually bigger in Texas. Take the mountains: The state’s gnarled ranges, wrought by volcanoes and warped by erosive epochs, are just half the height of the country’s great mountains, minor summits that seem like sentries for the West’s true marvels. They are eccentric and beautiful, though, especially the Chisos, nestled against the contested crook of Texas’ southern border inside Big Bend National Park. Serrated and strange like the mighty Cascades, intricately colored like castoffs of the Colorado Plateau, the Chisos are an amalgamation of American geologic splendor, built on the diminished scale of a child’s model sports car. They don’t wow; they mesmerize.

The Chisos must have made an apt prompt for Big Bend, the first soundtrack from Texas’ maestros of epiphanic atmospherics, Explosions in the Sky, in seven years. Big Bend grew out of the band’s work on the score for a splendid Nature documentary about the park, which premiered earlier this year. “Chisos,” its prelude, begins as a slow country shuffle, twilit guitars framed by a keyboard melody that cannot choose between a smile and a sulk. Likewise, just when the piece begins to shudder in anticipation of the kind of climax that made Explosions famous, the song begins to disintegrate, lazily vanishing into an endless sunset. Like the Texas peaks themselves, the moment—and the best of Big Bend at large—forgoes big drama in favor of something subtly spellbinding.

Big Bend itself is a “vibe park,” a place more striking on the whole than any of its specific highlights—there is no Half Dome, Grand Teton, or Grand Canyon. The harsh Chihuahuan Desert surrounds lush mountain meadows, while the Rio Grande flows just miles from incredibly arid expanses. Webbed together by a staggering array of wildlife, Big Bend is a gestalt of actual nature. Big Bend, the album, threads together 20 instrumental miniatures across an hour. Each frames an animal or an idea from the documentary, like bats that hunt on the ground or reptiles that appear to disappear into the desert. The pieces form their own subtle ecosystem, each informing the other rather than overriding.

There are, of course, moments when Explosions in the Sky do what you would expect—shape a sky-wide crescendo of glowing electric guitars, the rhythm section reinforcing an endlessly romantic frisson. “Sunrise” conjures an imagined Tim Riggins montage, where the Friday Night Lights star wakes up alone and hungover just in time to make a game-saving play. The piano of “Nightfall” first rises like a Nils Frahm fantasy. Marching drums and crisscrossing keyboard-and-guitar drones soon summon a bygone moment when the likes of Explosions, Sigur Rós, and M83 made dewy-eyed music that suggested everything was still possible.

But the bulk of these pieces explore less familiar terrain. “Autumn” unfurls like a brief Tangerine Dream homage, with distended synthesizer tones decorated by a neon guitar filigree. The sequential “Climbing Bear” and “Woodpecker”—two animals whose unexpected squabble over acorns makes the entire documentary worthwhile—convey both mischief and wonder with gentle acoustic guitars and restrained drums. Loping loops of pizzicato violin and pencil-thin guitar give “Swimming” a sense of childlike joy. It is perfect for the documentary’s footage of beavers cavorting in the Rio Grande; without the film, it is perfect for a brief afternoon reverie, a fleetingly rare moment of mental free play.

Explosions in the Sky began their work on Big Bend in the final half of the Trump presidency, as tension about inhumane policies at the Southern border escalated. They are releasing it now, amid another border crisis under yet another administration. The band hints at this troubled story of colonialism during “Human History,” the album’s finale and most clearly distressed six minutes. The music wallows, its circular piano and skittering electronics vying for vanishing air. That’s as close as they come to a statement—understandably, perhaps, given the nature of the Nature commission.

Perhaps now—that is, on an album about a natural wonder that has sometimes prompted humanitarian crises—seems like the moment for Explosions to be more direct, to reenlist the political undercurrents of their earliest work. But Big Bend honors the things we haven’t ruined in spite of our efforts, celebrating a wilderness our borders have yet to break. After nearly a quarter century, Explosions in the Sky have learned to leave us with the implication, not the epiphany itself.

0 comments:

Post a Comment