Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the album that made the Dave Matthews Band forever famous, in search of its long-overlooked dark heart.

The Dave Matthews Band seemed lame from the start. The quintet emerged, after all, at the beginning of the 1990s from Charlottesville, Virginia, a quaint college town better known then as a tourist hub for Shenandoah Mountain and Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved fiefdom than its music scene. Flanked by fiddle and saxophone, Matthews was a lanky white weirdo who sang about satellites, climate change, and the crucifixion of Christ like Kermit the Frog, raspy from all the weed. The locals lined up in throngs outside of clubs, coffeehouses, and frat parties to hear these anachronistic Grateful Dead acolytes.

But the truly big cities sounded different than the University of Virginia quad around 1992, with music that was unequivocally defiant or unabashedly snotty. Hip-hop poured into the heartland from both coasts, locked in a steadily escalating duel. Seattle’s grunge scene spawned a web of glowering toughies, all pursuing fiscal nirvana. And indie rock drifted toward wider prominence, abetted by a fawning music press and loaded major labels. By 1994, Pavement’s Stephen Malkmus was the cool-kid avatar exported from Charlottesville. Matthews was just the town’s astronomically profitable punchline, a magnet for and magnate of hippies and yuppies. “Matthews jams politely,” Robert Christgau ribbed the band’s 1994 studio debut, Under the Table and Dreaming. “He’s as bland as a tofu sandwich.”

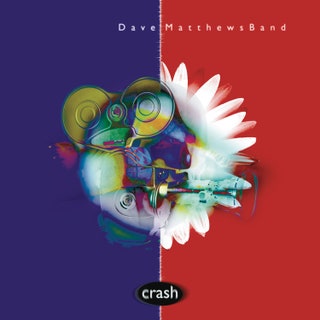

In the spring of 1996, nearly five years to the day after their first performance, the Dave Matthews Band declared that coolness would never be their credo. Crash, their second studio album, burrowed deeper into the idiomatic musical mélange that had made them popular and polarizing. The funk hit harder. The ballads luxuriated in deep moods, sexy or solemn. There were pan-African instrumental duets, velvety saxophone solos, and snarling acoustic rockers. Oh, and of course there was “Crash Into Me,” a once-ubiquitous precoital standard for some that doubled as an onanistic anathema for others. Crash typecast the Dave Matthews Band as the neoliberal darlings of Bill Clinton’s happy, wealthy, largely white United States, a sound perfectly suited for a second term.

A quarter-century later, that assessment feels superficial, overlooking not only the album’s dark heart but the way the band presaged the collapsing borders between genres, between pop and everything else. Crash made the Dave Matthews Band a beloved household name and one of the most reviled acts in the history of contemporary rock’n’roll, fodder for competing visions of how music should function.

The biography of Matthews himself cuts to the roots of his band’s head-scratching lineup and sound and their surprisingly enduring relevance, especially on Crash. It likely doesn’t resemble that of his legion of disciples, either—namely, the youngest Gen Xers or oldest Millennials who learned the horny “Crash” or the philosophizing “Typical Situation” to woo anyone within earshot of their state school’s dormitory.

Born in 1967 in a suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa, Matthews followed his family between England and New York for much of his first decade, accompanying a father who worked as “one of the granddaddies of the superconductor,” he once told Rolling Stone. But his father, John, died of cancer when Matthews was 10, prompting the family of five to return to South Africa after three decades of apartheid rule. Back in one of the world’s most destabilized political climates, Matthews learned about pacifism, activism, and resistance from his mother, Valerie, while absorbing the country’s native sounds and imported Western pop. A lackluster student, he indulged instead in listening to music, drawing, and acting. He bucked apartheid strictures, too, like a teenage punk. As he once told Spin, he’d lift his Black friends and physically carry them into segregated businesses. “See, they’re not touching the floor,” he’d say, taunting the staff, “so they’re not really here.”

To avoid South African military service, though, Matthews fled to the United States in the mid-’80s. Around the age of 19, he settled with his family in Charlottesville, where his father had once taught. Matthews soon found a downtown bartending job, a natural fit given his quick wit and knack for impersonations. There, he encountered a fertile community of musicians motivated by improvisation and collaboration.

With his mind set on making a demo, Matthews first approached a regular from the bar—LeRoi Moore, a Southern jazz saxophonist with a languorous sense of melody. Moore had worked for years with the drummer Carter Beauford, an area hotshot and BET session player who seemed as busy as an entire beehive behind his kit. A friend soon recommended the electric bassist Stefan Lessard, a teenage phenom who had been raised by hippies but was now sneaking into bars to jam. Fiddler Boyd Tinsley, the last to join, broke any easy notion of how this racially diverse quintet might sound—jazz? rock? bluegrass? country? Arabic maqam? African highlife? Yes. From the very start, the quintet seemed like an awkward but interesting teenager during puberty, trying to suss out what all these strange parts could do.

The band’s star rose quickly, especially in their native South. They would play most anywhere at any time, from frat houses to warehouses. And thanks to a tape-trading network modeled after ones used by the Grateful Dead, they turned those early shows into a form of proto-viral marketing, so that the kids in Savannah knew the songs before the quintet even arrived from Chattanooga. They signed a major-label deal and sold three million copies of 1994’s Under the Table and Dreaming by the time they finished its follow-up, Crash.

In a way, their mainstream introduction felt hesitant, even unfinished. It seemed as if they understood that being an acoustic rock band with a fiddle and a saxophone (and not singing all-American epics like Bruce Springsteen) made them plenty weird three years after “punk broke.” Recorded to click tracks and polished by veteran producer Steve Lillywhite—the real rock star in the room thanks to his work with U2 and the Rolling Stones—its songs were peppy or sentimental, snappy or pleasant, avoiding any liminal sense of danger. Months before it was released, one of Matthews’ sisters, Anne, was murdered by her husband in South Africa, leaving Matthews and his other sister, Jane, to raise her children. The Dave Matthews Band’s subsequent ascent to fame as the happy-go-lucky band singing about marching ants was chased by the long tail of yet another family tragedy.

The success of Under the Table and Dreaming—and the band’s relentless tour schedule—served as a permission slip to push their panoply of sounds harder the second time. By the time they reconvened with Lillywhite for several months in upstate New York to record Crash, they’d been playing its songs for years, many of them already bootlegged fan-favorites. They burned through untold hours of tape, vamping in the same room while they tried to tease out fresh renditions of tunes their “Daveheads” already knew.

In retrospect, previous live versions of these songs sound like pencil sketches for grand paintings. On Crash, the band ping-pongs between gleeful aggression and droopy melancholy, between feather-light strings and heavyweight horns for a full hour. “Too Much” and “Tripping Billies” are supreme gutbucket funk, Matthews growling his way through the verses as Beauford and Lessard work the meter like it’s a championship racehorse. (James Brown would eventually join the band onstage.) That rhythm section is the secret to “Crash Into Me,” too, with Beauford’s drums pushing the song toward a climax that never comes. It is a maniacal tease, a musical illustration of the song’s unfulfilled desire.

While Moore and Tinsley take a few extended solos, most memorably during “#41,” Lillywhite smartly enlists them as textural experts alongside Tim Reynolds, the band’s longtime part-time guitarist. Moore’s baritone saxophone lines during the first four songs, for instance, add welcome ballast, a counterpoint to Matthews’ reedy tone and Beauford’s prancing rhythms. Tinsley’s violin howls beneath “Drive In Drive Out,” lending the song a sense of true madness, like Matthews’ brain is about to break.

Still, the most daring moment of Crash is “Say Goodbye,” which empties out of “#41” through a clever segue. The song begins with a flute-and-drums duet, Moore and Beauford darting around one another like two hummingbirds eyeing the same colorful blossom. Violin plucks and muted guitar chords bounce through the mix like free electrons. It is a clear callback to the South African Kwela Matthews would have heard in his youth, a prelude that slides into seductive pop. More adventurous than any moment on Under the Table and Dreaming, “Say Goodbye” is a testament to the Dave Matthews Band’s escalating will to incorporate almost anything into its dynamic.

This new fusion gave critics even bigger fits than before. While Christgau had given that “tofu sandwich” a C+, he refused to reward Crash with anything other than a typographical bomb. In Rolling Stone, Jim DeRogatis compared Matthews to Sting and the band to Roxy Music before dissing the album via an extended metaphor for Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. And in an issue with a leather-clad Roseanne on the cover, Spin’s blistering review deadpanned, “If the DMB hadn’t existed, Sesame Street would have had to invent them.”

Even the positive notices were littered with backhanded compliments, deploying phrases like “guitar wanking” or “You couldn’t mosh to it if you tried” as caveat emptors. It was as if, as far as the music literati were concerned, continued Dave Matthews Band fandom required a preemptive apology. A high-school nerd, I was an obsessive DMB fan, with binders full of bootleg CDs and a wardrobe consisting mostly of overpriced tour shirts. But as college began, I fell for the false binary these critics framed—you couldn’t simultaneously like the Dave Matthews Band and “serious music.” It took the better part of two decades for me to realize I’d been posing, that the Dave Matthews Band could also count as serious music.

Crash’s popular appeal, on the other hand, was both instant and extended. The record sold a million copies in two months, a pace that flagged only slightly during the next year. The band sold out Madison Square Garden in three hours, added a second show, and sold it out again. They were the unquestioned stars of that summer’s H.O.R.D.E. tour, permanently outstripping festival founders Blues Traveler. In 1997, “So Much to Say” won the band its only Grammy despite 11 career nominations, somehow besting the the Smashing Pumpkins, Oasis, Garbage, and the Wallflowers. (“Crash Into Me” would lose to the Wallflowers the next year.)

But the feel-good image that Crash’s sounds and sales created never quite comported with the songs themselves, the messages Matthews nested within the music. Naysayers often cite the Dave Matthews Band in the senescence of grunge, their giddiness supplanting that movement’s raw angst. But on Crash, Matthews mined the same emotional cores as Kurt Cobain—dejection, loneliness, anxiety, sexual and social frustration. Everything about their presentation—the sounds, the mood, the culture—was different, but the sentiments were often the same. This semblance is perhaps clearest on the 1999 album Live at Luther College, the fifth show from Matthews’ 1996 acoustic tour alongside Reynolds just as Crash was being finished. It is their MTV Unplugged, the songs stripped to their essence. Without its horns, “#41” sounds broken and mournful, wallowing in hurt. It is a gorgeous elegy for innocence.

Indeed, Crash’s songs fit neatly into three broad categories, each a bit more serious than the album’s musical buoyance may suggest. There are, most famously, three songs about unrequited love and lust, a nascent rock star pining for sex he will never have. “Crash Into Me” epitomizes the idea, of course, with the true-to-life testimony of any teenager who’s ever fallen asleep in the throes of a fantasy. It is both creepy and quotidian, the testimony of a child confronting changing biochemistry.

Taken together, “Say Goodbye” and “Let You Down” shape a cautionary tale—the former a plea to forgo morals for a night of fireside adultery, the latter his mea culpa for the deed after it is done. Matthews was years into a courtship that led to marriage and children; this trio presents his subliminal timeline for learning to respect love amid the temptations of stardom and the exigencies of adulthood. He begins it as a boy staining the sheets; he ends it as a partner swallowing his pride.

A second triptych, scattered unevenly through these 69 minutes, represents what Matthews has long called his “seize-the-day” songs. These are his odes to living informed by those around him who have died, each anchored to a slogan fit for high-school yearbooks and cursive tattoos. “I can’t believe that we would lie in our graves/Dreaming of things we might have been,” goes the most mirthful one. “Celebrate we will/Because life is short but sweet for certain,” reads the moodiest, laced by pizzicato violin and eerie wafts of noise. And Matthews bastardizes multiple Bible verses at once for “Tripping Billies,” a gleeful Meters approximation that races with delight around a joyous violin line. All three remain live staples, each an enduring memento mori for a band and fans aging at the same pace.

But the most interesting parts of Crash—fully half the album—document Matthews’ interpersonal and sociopolitical woes. These laments are sometimes oblique. Seemingly ebullient opener “So Much to Say” lambastes our tendencies for small talk, for example, and demands we be something more honest and vulnerable, like a “little baby.” “#41” is a punch-drunk epic about the financial conflict that prompted the band to split with their first mentor and manager. It sounds elliptical and guarded, as though purposely written to avoid being entered into evidence during a lawsuit.

Matthews eventually squares up to that greed and concomitant cruelty. “Too Much” feels like one of those carpe diem anthems, with Matthews yowling and growling about eating and drinking over cataracts of bright horns and strata of snarling guitars. But it is a barbed indictment of American wastefulness at home, imperialism abroad, and how they’ve been normalized into a pernicious cycle. We use what we have here, Matthews sings with acrid glee, until we must crush someone else’s culture to get what they have, too. Played on Saturday Night Live and at the disastrous bacchanalia Woodstock ’99, “Too Much” is the Dave Matthews Band’s Trojan Horse, their way to soundtrack and excoriate the party in the same five-minute span.

“Cry Freedom,” on the other hand, is as musically unadorned and politically explicit as the band has ever been. Before and after, Matthews took care not to overstate his life as a young white man in South Africa, around for the beginning of the end of apartheid; he has assiduously avoided inserting himself into abuse that his heritage can never fully allow him to understand. But “Cry Freedom” takes its name from the 1987 film about Steve Biko, the South African revolutionary murdered by Afrikaner police a decade earlier. It is Matthews’ most straightforward lyrical reference to his childhood surroundings.

The band treats the subject with the reverence it deserves. Beauford taps out a simple beat over grayed guitar chords. Tinsley and Moore stretch long, woebegone tones behind it, the drapery blocking the sun from a room full of mourners. “How can I turn away?” Matthews sings softly at the start, framing himself as an ally. He maintains that cautious approach throughout “Cry Freedom,” reiterating that he’s only the anxious observer to this injustice, not the injured party. Though written about apartheid after its end, the song feels prescient for the United States 25 years later, a smoldering lament for a country of Blue Lives Matter banners that flap even as state-sponsored violence rages on. It is a salient reminder to be a witness, even if you’re not a savior.

Matthews’ outlook doesn’t resemble the vision of the United States that the saxophone-playing president broadcast at the time or the version that glassy-eyed suburban kids twirling on amphitheater lawns as the band played “Too Much” had likely experienced. Crash is dark, frustrated, and vulnerable, no matter how many hacky sack circles or light-beer-flavored makeout sessions its songs soundtracked. These messages are the secrets beneath the sounds; hearing them is like noticing the shadows that linger around the neon glow of Dan Flavin’s light sculptures or the turmoil lurking inside one of Meredith Monk’s exercises in vocal ecstasy. Crash is an album that actually longs to lift you up, not break you down.

There are a lot of reasons to deplore the Dave Matthews Band, to have never given Crash a second thought—so many, in fact, that speculating about them has become Matthews’ de facto sport during interviews. Perhaps you think Matthews sounds like he’s squeezing his voice from the warped horn of a tiny Victrola. Perhaps you think Beauford is always too fussy behind his drums (he certainly can be) or that the since-disgraced Tinsley was often out of tune, which isn’t wrong. Perhaps your relationship with “Crash Into Me” lacked the same redemption as that of Lady Bird. Or maybe they’re for you what the Doors are for me—an absolutely smoking band fronted by a self-important windbag. No act was more important to my rural childhood life, exposing me to so many musical ideas in the course of a single album that here I am, still pondering them. But all those complaints check out.

But the Dave Matthews Band fared well in the end. Crash made them superstars, pushing them to such popularity that they’ve been playing the same circuit of massive amphitheaters and arenas since they released it. That status eventually earned Matthews a tender-hearted cameo on Sesame Street and the band its own Ben & Jerry’s flavor, the delicious “One Sweet Whirled,” named for their most blatant example of hippie idealism. Their ultimate rejoinder to critics, however, was that they were right on Crash—right to pursue whatever sounds they loved, right to pile one unlikely element atop another, right to be weird in earnest.

A complete accounting of those that Crash influenced is both impossible and useless, an endless index of guitar strummers and kinetic drummers. Justin Vernon’s high-school band, for instance, thanked them in their adolescent liner notes. John Mayer sat in with them at the Hollywood Bowl in 2007 for a 14-minute rendition of “#41,” prefacing it with, “I’ve been waiting a long time to say this: I am who I am because of Dave Matthews Band.” Even Stevie Nicks has faithfully covered “Crash Into Me.” You could spend the better part of a lifetime watching covers of Crash songs on YouTube. (You probably shouldn’t.) More important than any single musician it helped shape, Crash helped give a generation of upstarts permission to do whatever they wanted with their own music. That sort of broad philosophical inspiration was altogether different than what Nirvana, Pavement, or most every other rock act cooler than the Dave Matthews Band supplied at the same time.

“That is bad as shit,” Beauford screams off-mic at the end of “Drive In Drive Out,” a frantic confessional about emotional torment. He is marveling at the tight-cornered rhythmic maze the band has navigated at top speed. It is, as he insists, bad as shit. I suppose that isn’t a cool thing to say about your own music on tape, especially on an album that will forever make you famous. But it sounds deeply felt and sincere, the core characteristics that always made Crash more compelling than its critics dared to admit.

%20Music%20Album%20Reviews.webp)

0 comments:

Post a Comment