Knit together with ambient passages and found sound, the teenage rapper and producer’s debut feels like a jumbled journey through folders of ideas, revealing new layers with every listen.

quinn cares deeply about how she is seen. Few photos or interviews with the 16-year-old rapper and producer from Virginia exist online. Her body of work lives on the digital fringes, sprawled across alt accounts and aliases. Explore her SoundCloud page cat mother for her latest experiments in drum’n’bass, or user-574126634 for a data dump of 30-second freakouts, intimate demos, and a bizarrely great Westside Gunn/Machine Girl mashup. Browse her website to view her virtual gallery of liminal space photos.

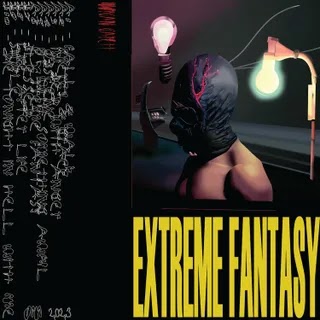

This scatteredness suggests an artist distancing herself from the notoriety she achieved in 2020 as one of the faces of hyperpop, after blowing up online with her song “i dont want that many friends in the first place” and becoming the first artist from her SoundCloud scene to appear on the cover of Spotify’s hyperpop playlist. (Due to technical complications, the music she’s released on streaming is currently still listed under the name p4rkr, a moniker she deaded nearly two years ago after coming out as trans.) As labels swooped in to sign teenaged peers like Glaive and ericdoa, quinn, who then went by osquinn, soured on the hyperpop tag and the visibility she’d gained. For several months leading into 2021, she deactivated her Twitter. In the spring, she re-emerged, announced she had been going through serious depression and quit vocal music, and released several meandering drum’n’bass and dark ambient records under the aliases cat mother and trench dog. On Twitter, I watched her collection of gear grow: Day by day, she would add another sampler or camera or pedal or synthesizer, proudly posting a photo and sometimes even sharing the work she’d used it to create. It’s how we see her on the cover of her self-produced debut, drive-by lullabies: her face obscured by a Pioneer DJ controller.

The artwork hints at how this album is sequenced: a jumbled journey through folders of ideas, with notions of temporality and genre flattened by the mix. It feels like a terminally online teenager clicking through tab after tab on a web browser, digging into different rabbit holes. Need a lo-fi rework of “Hands on the Wheel?” Check. A song that sounds like a deep-fried remix out of SoundCloud’s dariacore scene? Check. A random riddim explosion? quinn’s got you. The vocals are back, but this album prioritizes mood over the hookiness of her bigger singles from 2019 and 2020. Some songs have the spare, anxious feel of last year’s “mbn”; some fold in quinn’s recent forays into dark ambient and drum’n’bass; and the sole interlude, which quinn says she freestyled in 2018 at age 14, sounds like a kid’s earnest take on Some Rap Songs. Even back then, quinn’s music was about understanding how she is seen, navigating a gaze: “I was way, way better than my mom told me.” This was the thrust of the music that catapulted quinn into the mainstream last year, and it continues to power drive-by lullabies, a portrait of a small celebrity navigating personal life.

The sound design reveals new layers with every listen, showcasing the meticulous detailing quinn picked up during her turn to instrumental music. Those explorations sometimes felt aimless and imitative on their own; anchored by her warbling voice, they gain direction and burst to life. Droning ambient passages and bits of found sound accompany, break up, and rope together drifting verses, acting as a kind of glue for genre experimentation. It recalls the way her inspiration Dean Blunt wove the sound of water through several tracks on The Redeemer. But where Blunt’s voice is deep and resonant, quinn’s is round and warmly robotic. When her voice first emerges on “The World Is Ending Soon!” it’s like a sprite flowing from fog, born from a mess of static and guitar strums.

On that song, she begins charting a complicated relationship to an unnamed other, imagining how they might find each other when the “stars burn out and explode.” This connection serves as the emotional core of lullabies, a way of tying together the record’s moving parts. Still, lullabies sometimes threatens to spiral into creative oblivion. There’s a lot going on here—maybe too much for an introductory record. The instrumental song “birthday girl,” where a warped piano segues into a physician’s monologue on depression, might scan as overindulgent to even the steadiest quinn fans.

But to open ears, this album is a quiet thrill. There are brash moments that recall quinn’s older music, like “perfect imperfection,” which shakes out a drill rhythm before constructing a wall of synth noise, but lullabies largely finds beauty in smallness and rawness. On “silly,” you can hear quinn’s take on the soft, JRPG-like sounds percolating through dltzk’s Teen Week, kurtains’ insignia’s manor, and other 2021 digicore records. “coping mechanism” is simply gorgeous, quinn’s crushed-up vocals drifting past tiny glitches and birdsong. But then there’s the calm refrain, almost hilariously morbid: “Have you seen enough people die? I didn’t think so.”

The ambiguous “you” in this line is a device quinn deploys often to unpack gaze. In her knotty single “and most importantly, have fun,” it captures how being online and interacting with fans produces cognitive dissonance. On lullabies, it seems to map onto DMs and text messages, channeling how even the most intimate digital spaces reduce our bodies to vague directives. “See I want something to do with you,” she sings to a romantic interest on the gurgling “Change That.” This introduces a quietly captivating three-song suite that concludes the album’s relationship arc. Through tender exercises in indie rock and soft, cryptic language, she teases out details of a lack of mutual understanding, of mess-ups and miscommunication, of two people seeing past each other.

Critics love to frame the reigning internet music of the moment as a snapshot of an online generation, but quinn’s songs do not approximate a vague generational trend or aesthetic; they feel wrought from a place of private meaning, directed to a shapeshifting subject. She’s at her poetic best on “mallgrabber p,” weaving complicated feelings between two people into endearing, nursery-rhyme verses. quinn has cited countless artists as influences, from 100 gecs’ Laura Les and JPEGMAFIA to Sybyr and Duwap Kaine, but when I hear how quinn tumbles through the words here, I’m reminded of Lucy, an artist from Western Massachusetts whom quinn loves to shout out. Lucy found an online following in the mid-2010s as part of a collective called Dark World Records. His music was weird and funny and, like quinn’s, disarmingly earnest. But right as that group was on the verge of a real breakthrough, Lucy left Dark World and retreated from the internet limelight. He pursued his joyous outsider music away from the press, bringing small crowds to basement shows around New England. Then, last spring, he re-emerged with an album called The Music Industry Is Poisonous. Listening closely to drive-by lullabies, you can imagine quinn feels the same way.

0 comments:

Post a Comment