The third volume of Light in the Attic’s ongoing survey of this largely notional movement puts a new twist on the idea of combining two seemingly incompatible genres in one unruly sound.

One of the unsung qualities of Country Funk Vol. I and Country Funk Vol. II was their casual disregard for history. Documenting a scene that wasn’t really a scene and not even much of a movement, they traced a mere idea—hey, let’s combine country twang with funk rhythms!—across a couple dozen tracks from the late 1960s through the mid 1970s. Neither bothered to put the songs in chronological order; in fact, the two volumes themselves weren’t in order, with Vol. II covering a slightly earlier time frame (1967-1974) than Vol. I (1969-1975). Those spans didn’t even represent particularly salient mile markers; they were just the dates of the songs the producers wanted us to hear. They were more like mixtapes than reissues, which fit the gritty, sometimes funny, occasionally sexy, often bizarre music perfectly well.

Almost by necessity, this long-awaited third volume is a bit more aware of the past. It picks up roughly where the other two left off and follows that idea into the early 1980s. Still scrambling the timeline in its sequencing, the collection can’t help but track the changes that both country and funk but especially country-funk endured as one decade ended and the next began. Vol. III covers 1975 through 1982, a period that saw the end of outlaw country and Southern rock, the beginnings of yacht rock, the rise and fall of disco, the start of the Reagan era, and the arrival of new sounds and technologies in pop music, all of which affected the music collected on this new compilation.

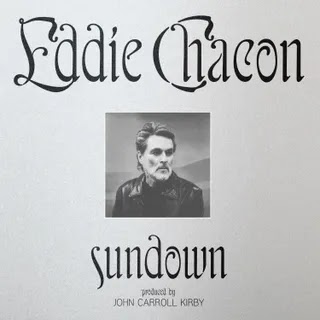

So set aside your disappointment that Jess Rotter didn’t return to draw the cover; this set succeeds because it puts a twist on the whole idea of combining these two genres into one unruly sound. The yacht-country strains of Eddie Rabbitt’s “One and Only One,” with its breezy vocals, percolating rhythm section, and genius rhyme scheme (“Baby, you’ll always be my special… lady”), would have sounded jarring on the first two volumes, but it fits nicely within this wider array of sounds. Jerry Reed projects boundless hick charm on “Rhythm and Blues,” and Delbert McClinton goes cowboy noir on “Shot From the Saddle,” which gets its boogie from, of all things, an alto saxophone. The funkiest thing about Dolly Parton’s disco-adjacent “Sure Thing” is the way she sings that title, hoarsely drawing out the ur in sure with a wink and a nudge.

Some of these country artists, including Parton, used funk sounds as a springboard to cross over into the pop market, while others struggled to adapt. Tony Joe White was caught between the mainstream hitmaker he’d been in the late ’60s and the cult artist he’d eventually become, and “Alone at Last” (released here for the first time) shows why he was flailing commercially: That low voice still sounds compelling and weird in its phrasing and intonation, but it’s paired with a chintzy keyboard that is the very opposite of funky. (Side note: Is he actually singing, “The first time your ass touched mine, I knew we’d get together somehow”?) Ronnie Milsap, on the other hand, was on the cusp of crossing over to a pop audience when he cut “Get It Up” in 1979, sounding like a man so unhinged by lust that he mistakes the discotheque for a honkytonk.

Sex remains one of country funk’s favorite topics, and Vol. III tracks some changing attitudes about getting it on. There’s nothing here that’ll make you blush as scarlet as Bobbie Gentry’s “He Made a Woman Out of Me” did on Vol. I, but Rob Galbraith’s “I Got the Fever” comes awfully close, specifically the way he delivers the line, “You got me feeling so illegal.” And Terri Gibbs delivers a rags-to-riches story worthy of Joan Collins: On “Rich Man,” she plays a woman who uses her wiles to snare a wealthy husband and has fun doing it. Best of all, Gary & Sandy combine sex and sci-fi on “Gonna Let You Have It,” which is Gary, Sandy, a tight rhythm section, and a phalanx of laser blasters. Over a galloping melody, the duo equates shootouts with hookups, with Sandy turning even the most cliched lines into come-ons: “Gonna open fire… with sweet desire.”

It may be obvious by now that the best moments here are the most outrageous, the ones that lead country music way out into some deeply weird pastures. And none get weirder than Billy Swan’s 1977 not-a-hit “Oliver Swan,” which opens as a character sketch about a town drunk who “smelled like a dead skunk.” Despite that supremely infectious organ lick and shuffling drumbeat, it plays like one of those somber Southern slice-of-life songs, similar to Mac Davis’ “Lucas Was a Redneck,” from Vol. I. Then it takes a truly strange turn: “Then one night a saucer flew down from the sky, full of another world’s women saying, ‘We need us a guy!’” They abduct him, hold intergalactic orgies, and repopulate their planet, and Billy Swan wraps it up by describing a “bunch of little green Oliver Swans.” There’s a mischievous edge to his delivery, as though he can barely suppress a laugh. It’s the beautifully ridiculous centerpiece of this collection.

Even at its most absurd, there’s a tinge of sadness to Vol. III, as though the artists and the compilers understand that something is coming to an end. The ’80s weren’t necessarily kind to country funk, as many of these artists aged out of the mainstream and were replaced first by Nashville neo-traditionalists who viewed innovation with suspicion and later by hat acts more interested in rock than funk. A theoretical Vol. IV could dive deep underground, although half the fun of these weird compilations is knowing that these artists and sounds had infiltrated the mainstream to some degree. Or it could simply backtrack and see what was happening from 1974 through 1981. Until then, Dennis Linde’s frantically upbeat “Down to the Station” serves as a fitting send-off to this unlikely marriage of two seemingly incompatible styles. “Feeling fine at the station, I ain’t even gonna look back,” sings the man who wrote both “Burning Love” and “Goodbye Earl.” “I ain’t worried about tomorrow, it ain’t here and I ain’t there.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment