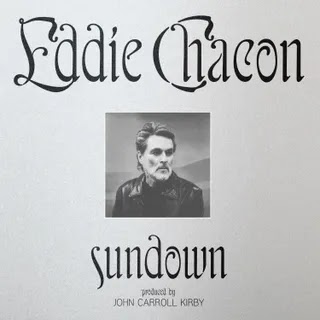

On his third solo album, Jack Antonoff ends up splitting his time between careful rock songwriting and carefree pop singing, leaving a minor impression of both.

There’s a strain of Tasteful Pop coursing through mainstream music right now, guided by Jack Antonoff’s princely hand. Taylor Swift and Lana Del Rey and Clairo and Lorde have all recruited Antonoff as co-pilot on their journey to the soft and lush grounds of Tasteful Pop, cushioned by string arrangements and acoustic guitars and first-person observational songwriting that always seems to ask what is honest right now? as opposed to what might sound interesting later? As a producer, he is more than a hired gun but never an egomaniac, just the footprints in the sand when you need him the most. Even when working on funky ’70s pastiche with St. Vincent or the pop-country of the Chicks, Antonoff remains collaborative, chameleonic, versatile, and difficult to pin down save for one word: tasteful. And there is no accounting for taste.

His third solo album as Bleachers, Take the Sadness Out of Saturday Night, threatens to blow that whole idea out of the water. It’s a confused album that sounds like it wants to sit on the shelf next to do-it-all pop savants like Jeff Lynne or Todd Rundgren, yet retreats to the safety of Antonoff’s alt-pop impulses before anything spectacular really develops. Everything feels a little too sweaty and effortful, and the yelpy millennial-pop singles gobble up the scenery behind more nuanced and emotionally textured album cuts. Though it’s an album led by a bona fide hit-maker, it is perfumed with the notice-me-dad odor of a solo project. It is mostly inspired, sometimes interesting, and occasionally banal, half All Things Must Pass, half Jack Antonoff and the G League Band.

Antonoff recorded these sessions with his five-piece touring band during the pandemic, crafting an album about falling in love with the sound of the slapback echo. I’m kidding, but not really. The production effect—made famous by Elvis Presley in Sun Studios, a hallmark of ’50s and ’60s rock’n’roll, and used by many since then from Bruce Springsteen to Wolf Parade—is essentially a sixth band member, coloring the songs with a sepia, rockabilly tint. It is the first hint at Antonoff’s desire to create a real album’s album.

On 2014’s Strange Desire and 2017’s Gone Now, he celebrated his nostalgia for the ’80s, but now he seeks something even further in the past, summoning images of lyrics scrawled on foxed pages and captured with vintage microphones. This feeling begins with the lovely “91,” co-written and sung with the author Zadie Smith. The slow prelude has an expressionistic, dreamlike quality, a spectral memory play set in 1991, where there’s a war on TV and a mother waltzing around a room “like there ain’t no rip in the seam.”

Mothers, ghosts, faith, and darkness are a few of the motifs across Saturday Night, cropping up like Bruce-shaped signposts along the side of the turnpike. Antonoff even calls in Bruce—his childhood idol and chief musical and spiritual inspiration—to join him on “Chinatown,” a song that feels like a spec script for a Bruce Springsteen song, glockenspiel and all. (The first line: “Get in my backseat, honey pie, and I’ll wear your sadness like it’s mine.”) It conjures big nights and bigger tomorrows like some viral video where Bruce joins a wedding band on stage—kind of lovely and sad and small at the same time. Antonoff told Billboard that this album was “always about breaking out, knocking at the door of the next phase of your life.” Bruce wouldn’t knock, though—he’d kick it down.

In that way, the nervous and quieter parts of the record are where Antonoff separates himself from his pop career. “Big Life” sounds like a songwriter who knows the rules and is willingly destroying them with a preposterous amount of slapback echo, a surfy guitar riff, and an opening line that is funny and self-lacerating: “I flip back and forth coast to coast like an herb.” There’s a lot of odd creases like this, nerdy songwriter/producer choices that highlight Antonoff’s love of making records: The way he sings the title of the album on two separate songs; the close-mic’d vocals and how they strangely overlap each other on closer “What’d I Do With All This Faith”; the clear homage to another inspiration of his, the Mountain Goats’ John Darnielle, on the acoustic heart-pumper “45.” It is the quintessential Antonoff solo song, the self-professed herb strumming a guitar and singing his heart out about music and records and love.

The bigger swings at pop-rock are when everything gets blurry and Antonoff pulls a muscle trying to make another hit. “Stop Making This Hurt” is a horn-filled, chest-beating Garden State anthem with a shout-scream chorus as welcome as a troupe of theater kids doing an impromptu number at an IHOP. The big rave-up “How Dare You Want More” fares a little better because it sounds like it was recorded all huddled around one mic, the kind of infectious live-show staple that might really cook if it didn’t stall out completely when the guitar and saxophone start miserably trading fours. It’s rare to find a moment on any record where it seems worth remarking how bad a solo sounds, but there it is.

“I talk so much because I’m scared to begin,” he sings on “Secret Life,” the best and most revealing line on the album. The anxiousness and confusion that bloom in the album’s smaller moments hide behind the bigger songs, which, for all their ’80s and ’50s worship, still sound tailormade for schlocky alt-pop radio. Antonoff remains a curious case for a solo artist, this perennial kid brother archetype with a grin stained on his face even when he’s trying to look serious. His leather jacket says rock star, but his songs are mostly without danger or angst. And even in their hangdog sadness, they are always eager to be heard, yipping at your shins as opposed to inviting you in.

0 comments:

Post a Comment