Quality Control’s secret weapon sticks to his crunk roots on his new album while also venturing into the most known unknown.

Memphis, like the entire South for many years, was so ignored or disrespected by the rap industry that the city’s scene developed a remarkable sense of self-sufficiency. DJ Paul and Juicy J started off making their own beats; and today, Young Dolph is at the level of a major-label star but maintains independence through his label Paper Route Empire, offering a Black-owned network of support to younger rappers from the 901. That sense of community and self-reliance is, in many ways, the essence of Memphis—the Orange Mound neighborhood was one of the first in the country in which Black residents owned, rather than rented, their homes, allowing for a certain amount of autonomy not afforded to Black Americans. Memphis’ spirit of self-determination and independence is at the heart of the music of Duke Deuce, the slyly emerging secret weapon in Quality Control’s stable who expands beyond the regional acclaim of his Memphis Massacre mixtape series on new album DUKE NUKEM.

Duke, born and bred in Blackhaven, came of age during his city’s most mainstream moment—the era of “Stay Fly” and Yo Gotti’s prolific mixtape run—but his connection to his hometown’s rap goes beyond mere fandom. He grew up in the studio alongside his father, Duke Nitty, a producer for the likes of former Three 6 member Gangsta Blac and Nasty Nardo during the true underground days. Most of Nitty’s credits stem from the turn-of-the-millennium, but at the encouragement of his son, the elder Duke has returned to beat-making. Deuce enlists features from artists outside West Tennessee but still keeps his homegrown sound strictly in the family, as generations of Memphis rappers have done—Juicy J and Project Pat are brothers, after all, and early major label signee Gangsta Pat learned the tools of the music trade from his father Willie Hall, percussionist for Isaac Hayes and Stax Records.

Duke’s album title references the iconic video game character Duke Nukem, who alongside Doom and Wolfenstein solidified the first-person shooter as one of gaming’s hegemonic genres. Nukem retrofitted 1980s action for Generation X, combining the hard bodies of Schwarzenegger and Stallone with an ironic, Simpsons-like smarm and the transgressive, tongue-in-cheek edge of the Attitude Era. Some of Nukem’s most infamous catchphrases are quotes from Bruce Campbell in Army of Darkness and Rowdy “Roddy” Piper in They Live; and the atomic action figure and his bleach-blonde flat-top are physically modeled after Dolph, Van Damme, and pro football player turned failed action star Brian “The Boz” Bosworth.

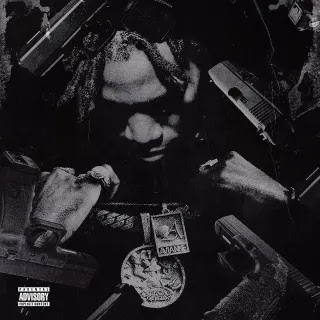

In the same way that Duke Nukem was a pastiche of action movies past, Duke Deuce draws himself a cartoon persona out of old Southern rap tropes. His relentless beats often sound like military marches, timpanis thumping in-between trap hi-hats, and DUKE NUKEM appropriately has an army theme. “Soldiers Steppin” opens with the ten-hut chants of a platoon before Duke commands you to march, with a finger in your face like R. Lee Ermey. The No Limit-like iconography carries over into the packaging: the futuristic cover by KD Designz, with green plastic army men, Duke’s head fashioned into a nuclear bomb, and his constant and iconic “What the FUUUUUCK!” ad-lib rendered as an explosion; song titles like “Army” and “Soldiers Steppin”; music videos themed around buck boot camp drills and Nukem-inspired video game levels.

While most Memphis revivalists opt for the haunted tongue-twisting of Lord Infamous, Duke Deuce feels more influenced by the pitter-patter flows of Project Pat, a goofy court jester and absolute unit as much as he is a slick-talking player of the game. Duke frequently speaks of himself in the third person, as if he’s the Incredible Hulk about to smash the club up. He has a Bruce Banner side, of course, slipping into something more mournful and soulful on “Army.”

DUKE NUKEM is an album made with the club in mind—as Duke puts it on “Soldiers Steppin,” “2020 fucked up, so we back up on that crunk shit”—but there’s a kind of intricate weirdness to much of the instrumentation and production: the warbling, almost out-of-tune keys on “Duke Skywalker”; a distorted and shuffling loop a little lower in the mix on “Toot Toot”; a grave hum underneath Duke’s voice on “Move.” Duke brings together old and new generations of the 901; multiple tracks are produced by Hitkidd, who in addition to collaborations with Memphis artists like Blocboy JB and former Raider Klan members Xavier Wulf and Chris Travis, has produced for Bladee and Yung Lean, showing the global influence of the Memphis underground sound.

Some of the guests that Duke drafts owe a debt to Memphis: like A$AP Ferg on “Fell Up in the Club,” whose blockbuster “Plain Jane” took its structure from “Slob on my Knob,” or fellow Quality Control comrade Offset on “Gangsta Party”—what was the much-heralded triplet “Migos Flow” if not a refurbished take on Three 6’s dense delivery? Duke doesn’t just draw from the same well of Hypnotized Minds-licensed records—the first sound on the album aside from Duke’s voice, on the 8Ball & MJG-nodding “Into: Coming Out Hard,” is a brief sample of the Stooges’ “Dirt,” directly linking Southern crunk and punk mosh pits. “Fell Up in the Club” is built from a flip of a true regional underground hit that’s probably only known by a few outside Shelby County, EP da PaperChaser and Dow Jones’ “PaperChase,” which I can only imagine would have soundtracked a lot of school dances and parking lot hangs when Duke was growing up, him and his friends trying to perfect the jookin move of the same name.

Unlike so many who bite the mystic style born in Memphis, Duke Deuce was born there, too; it’s not just samples or a flow to him—crunk is an entire culture, and it’s in his blood. So much of rap is built on riffing on or playing off music history, but there’s a thin line between reinterpretation and repetition. Duke Deuce holds to certain traditions while also venturing into the most known unknown. Crunk isn’t dead, and it’s not an undead zombie of its former self, either: Duke knows and respects his history, but he’s detonating it to make way for something new.

0 comments:

Post a Comment