Featuring the magisterial Dusty in Memphis, its lesser follow-up A Brand New Me, and a bevy of related tracks, a new collection captures one of pop’s most fascinating personalities in her second act.

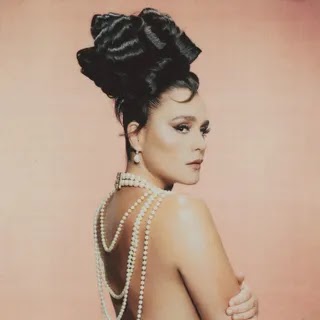

By 1968, Dusty Springfield had begun to suspect that there was no easy way down. Cool enough to duet with Jimi Hendrix on her regrettably named ITV show It Must Be Dusty but hobbled by increasingly dowdy material, Springfield realized it wasn’t a good time for singers with bouffant hairstyles who hoped to stay hip. Signing with Atlantic and relocating to Memphis that year looked like a smart move, resulting in a body of work as substantial as Aretha Franklin’s own Atlantic recordings. The Complete Atlantic Singles 1968-1971 collects the magisterial Dusty in Memphis (1969), its lesser follow-up A Brand New Me (1970), and a bevy of tracks orbiting the albums like lonely satellites.

Before turning to this fecund epoch, it’s important to appreciate Springfield’s achievements. To savor the run of singles recorded between 1963 and 1967, from “I Only Want to Be With You” to “The Look of Love” means appreciating Springfield’s combination of winsomeness and submersion; unlike Dionne Warwick, another beneficiary of Burt Bacharach and Hal David’s compositions, Springfield wasn’t detached, as her performance of the 1966 Pino Donaggio and Vito Pallavicini composition “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” rewritten in English, testifies. But Springfield, who wrote a song here and there and exerted more production control than credits aver, had grown restless. She insisted on working with the redoubtable producer Jerry Wexler. The eight songs he brought to what became Dusty in Memphis represented the best of the so-called Brill Building songwriters: Carole King and Gerry Goffin, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil. Randy Newman and Michel Legrand chipped in too. With Arif Mardin and engineer Tom Dowd joining Wexler, the venture had promise.

A combination of Springfield’s mild anxiety about singing live with a rhythm section and her insistence on controlling the material stalled the project at first. “To say yes to one song was seen as a lifetime commitment,” Wexler carped later. Most of the vocals she eventually recorded in New York, a development with no bearing on the album’s swampy, undulating sonics: Dusty was in the fantasy-selling business. Aretha had already rejected a John Hurley-Ronnie Wilkins soul number called “Son of a Preacher Man.” Time and impatience with the Pulp Fiction mythos hasn’t dulled Springfield’s signature tune, in which she sasses and upbraids one “Billy” while an ebullient horn section blows its support and bassist Tommy Cogbill plucks the sweetest line she’d ever sung over. So self-assured was Springfield’s performance that Franklin recorded a version for This Girl’s in Love with You (1970)—and it’s merely decent (Springfield and Annie Lennox remain the only women to have gone eye-to-eye with Franklin and survived).

Bifurcating erotic abandon and a melancholy as permanent as soul death, the rest of Dusty in Memphis depends on the intuitiveness with which the players and the singer understand their respective needs: Springfield’s for ballast, house band the Memphis Boys for ethereality. It’s not a concept album as such but it often unfolds like one: Dusty Springfield recreating herself as lover and loved, essaying her stylized version of soul music. “It is a love that is all at once diffuse, dark, unpredictable, ecstatic, and a terrible deal,” Warren Zane speculated in his 33 1/3 book on the album. This sparkling remix underscores the achievements: the oboe in “I Don’t Want to Hear It Anymore” circling her mediations like a long-legged fly; Reggie Young’s forlorn guitar arpeggio in “Just One Smile” and—it was 1968—his sitar in “In the Land of Make Believe.” Singers dependent on an upper register risk tiring listeners with their intensity; with Springfield, the syllable-at-a-time approach noted by future producer Neil Tennant, torturous to her current record makers, transforms her into a co-creator. Tangling the sensual and the threatening, she masters assonance (“br-eh-kfast in b-ehhh-d”), discretion (quietly breathy in the verses of “Don’t Forget About Me” as if afraid of wearing out a welcome), timing (a full stop for each word in the chorus of “No Easy Way Down”).

A Brand New Me steps away from the brink. Relocating from Memphis to Philadelphia with songwriter-producers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, Springfield doesn’t inhabit the material: she externalizes it. The album is soft-focus, blurry. Gamble and Huff approach her as if circling a runway. Sweet banalities like “Bad Case of the Blues” unfurl alongside gutbucket funk pop like “Lost.” The title track, her last American Top 40 hit until 1988, is a manifesto in search of a cause. The mildly bossa nova-flavored “Let Me in Your Way” works best: Springfield follows bassist Ronnie Baker’s melody. For a hint of what could’ve been, look to the bonus material collected on the anthology, most of which has found homes on reissues of the studio albums over the years: “Haunted,” graced with swampy organ lick, and a momentum similar to Martha and the Vandellas’ “Nowhere to Run”; the way in which “Someone Who Cares” switches from cocktail ballad despondency to I’m-here-to-tell-ya euphoria; and “Willie and Laura Mae Jones,” a sharecropper-era fantasia by Tony Joe White in which the cotton is high and the corn is growin’ fine.

One part of that tale rings true: lots of corn, fine and high, on the last half of this compilation—itself redundant, for remastered and expanded versions of both albums have existed for years. Yet Dusty Springfield remains one of pop’s most fascinating, protean personalities. Not just a British woman singing R&B but a queer British woman, she dwelled in a sinister twilight where objects of desire bobbed gender-fluid but no less distracting. She was the poet of the afterglow. The 1970s she spent doing TV theme material and backing vocals for buddies like Elton John; after the collapse of her relationship with erstwhile collaborator Norma Tanega, she was scared about British tabloids outing her. She waited a pop eternity for Tennant and Chris Lowe, aglow with childhood memories of her and Cilla Black and Sandie Shaw, to give her sympathetic arrangements again. Like Gladys Knight and her Pips, Springfield needed backtalking backup singers and horn blasts after breakfast in bed. The Complete Atlantic Singles is the un-easiest of listening. Thank Dusty Springfield.

0 comments:

Post a Comment