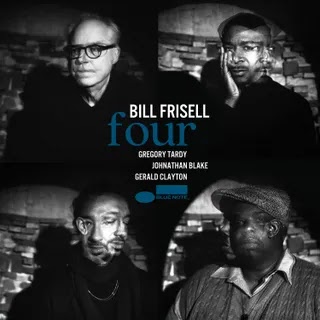

On violin, guitar, saxophone, percussion, and keys, the quartet pieces together a carefully arranged mixture of jazz, ambient, folk, and classical minimalism.

Seasons change in the mind and the body before they change in the world. Anyone who has felt spring bloom in their hearts on the first false day of sunshine, or been transported to autumns past by the crunch of a stray brown leaf on a late-summer afternoon, knows that climatological reality is not always in sync with our perception of how things should be. The Japanese word “fuubutsushi” refers to this gap, capturing the feeling of longing for a new season at the first signs of its emergence. After months of life looking like one thing, fuubutsushi marks the moment when you believe it may begin to look like something else.

That feeling—not the out-of-time displacement of hope, so much, or the rush of anticipation, but the embodied understanding that things are about to change—suffuses this collaboration between violinist Chris Jusell, guitarist Chaz Prymek, percussionist and keyboardist Matthew Sage, and saxophonist Patrick Shiroishi. All four are prolific composers who have hooked up in various configurations in the past, often playing challenging takes on jazz and ambient music. For Fuubutsushi (風物詩), which was recorded remotely with each musician in a different U.S. state, they piece together soothing bits of jazz, ambient, folk, and classical minimalism with the ease and grace of a group of pals working on a jigsaw puzzle over warm cider. Listening to it can feel a little like relaxing in the home you imagine as you unpack your belongings in a new apartment: Everything is expertly placed and arranged with care.

Fuubutsushi’s spacious production highlights the performances of the individual players, which in turn makes their interactions ring more clearly. In “Along the Causeway,” Sage’s piano rolls forward like a ball losing momentum uphill, falling back into a figure that recalls both the clipped phrases of Ethiopian classical music and the good cheer of Joe Hisaishi. Shiroishi takes the cue and flits alongside at the same pace, the early-morning hoarseness of his tone matched by Jusell’s violin. This focus on clarity recalls the famed production style of ECM Records, but Fuubutsushi is almost entirely lacking the high-minded stakes that underlie so much of that label’s work. This is less a conscious shot for posterity than a conversation among intimates.

Still, that conversation frequently touches on the profound. On album opener “Bolted Orange,” whose kindheartedness recalls Sam Wilkes’ WILKES, they patiently fill space with the softest of interactions, as if they’re passing around a Fabergé egg. Jusell’s melodic sense reaches a peak in “Hayao’s Garden,” bringing to mind the stark drama of Björk, while flickering backmasked samples light up and are gone in a flash of poignance. Even “Watch the Time,” a “Hallogallo”-esque krautrocker that’s easily the album’s most upbeat song, evolves into something like Steve Reich’s Different Trains scaled down to living-room size. True to its title, nostalgia and longing permeate the album, along with a prevailing remembrance of how thin the present moment can be.

In the hands of lesser artists, all this focus on the fleeting nature of beauty and the quiet erasure of time could easily drift into the saccharine, carried along on a stream of sentiment like a plastic bag on the wind. Jusell, Prymek, Sage, and Shiroishi seem to know it, and they willingly puncture any potential fragility with good humor, excellent pacing, and reminders of the world outside, an approach that reaches its apotheosis on album centerpiece “Freedom and Crap.” While the quartet tinkers with a miniature, two unidentified people speak about their experiences in some kind of prison. “I was kinda wistful for what was outside of the fence,” a female voice remarks, while a male voice concludes his story by saying, “I can’t imagine anybody liking it or having positive images of being locked up.” While the group treats this material with the reverence it deserves, they never slip into the po-faced. Without being avoidant, they create a soundscape that’s playful and loose; it’s like visiting Ernest Hoods’s Neighborhoods on a drizzly day. Rather than sensationalize the stories, the subdued mood highlights how tragically common they are.

At this stage in our year of quarantine, it seems impossible not to empathize with those who are subject to incarceration. The need for true human connection has never been more obvious, and the intimacies we can achieve with one another have rarely felt so precious. Recorded a few months into lockdown, Fuubutsushi glows with this awareness: that even in our present darkness, there’s something beautiful, mysterious, and vital that’s generated when old friends find new ways to come together again, against all odds and as natural as can be.

0 comments:

Post a Comment