On his third album of 2020 and first for Griselda Records, the Detroit rapper continues to pry open windows onto his past, soul, and psyche.

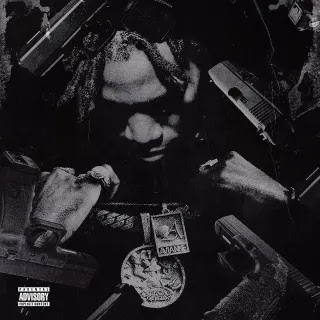

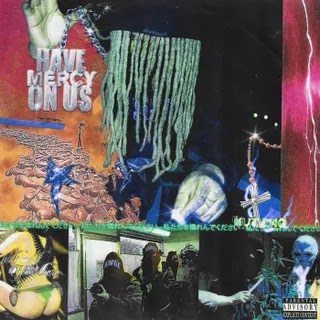

The Versace Tape is the third album the Detroit rapper Boldy James has released in the last six months. It follows February’s The Price of Tea in China, a skeletal but psychedelic collaboration with the acclaimed Los Angeles producer Alchemist, and last month’s constantly molting Manager on McNichols, which was helmed by the veteran but comparatively obscure Sterling Toles, from Boldy’s hometown. Versace pairs the rapper with someone from, well, the internet: Jay Versace, the former Vine star who has lately turned to producing music. It was a surprise this spring when Versace popped up in the credits of Westside Gunn’s Pray for Paris; The Versace Tape is Boldy’s first album for Griselda Records, the label co-founded by Gunn, and fits neatly into a machine that promises steely, ambitious street rap, delivered at regular intervals.

Boldy’s catalog has the quality of genre fiction: his songs hit familiar notes and live in an instantly recognizable milieu. The style is repeatable without being repetitive, its dials tweaked slightly for each new iteration. The Versace Tape’s intro smartly signals that the rapper has refitted his approach for Griselda Records, whose releases––especially Gunn’s––are littered with, and in some ways defined by, references to luxury goods. This intro is a local news clip about a thief who walks into a gas station and steals a “very expensive pair of Cartier glasses” right off of a victim’s face before sauntering out the door and into a waiting car. The police, this news anchor says, described the suspect as “bold and nonchalant.”

That nonchalance is one of Boldy’s signatures; it’s slyly funny when, on the already muted “Maria,” he deadpans that all the money he’s been raking in is making him emotional. Early on “Brick Van Exel”––he can cook with his left hand––Boldy recalls two generations of his relatives growing into the drug trade. The moment is allowed to land, but not linger; there are instructions about burner phones and stern warnings to give. Later on in the same song, he raps, “Every time I met up with the plug, felt like a setup,” before once again dropping that idea to follow a new tangent. This structure and affect makes his music compulsively listenable, because it suggests these stark personal revelations and jaw-dropping asides will be meted out consistently, as if from a metronome. They are.

Versace’s beats are similarly reliable. It is perhaps ironic that such an antic internet personality is turning out beats that fit so neatly in the post-Dilla, -Madlib, -Marcberg world of contemporary underground street rap, where drums are of little concern and loops are often laid bare. This album is warm, as if it was all dipped in sepia.

To that point, one of the most pleasantly surprising aspects of Boldy’s work this year is the sentimentality that creeps in at the margins. “Long Live Julio,” one of the record’s standout tracks, begins with an ad-libbed redux of a famous Eazy-E hook, where the “boys in the hood” are not meant to be menacing and mythic, but rather young and full of promise, frozen in memory. Boldy throws the song into fourth-period lunchrooms and cramped bathrooms where he’s scrubbing Nikes with a toothbrush; he makes the life sentences that hang over murder cases sound like speedbumps in his school parking lot.

Even in these moments, though, Boldy is the consummate technician. From the time he says “Rest in peace, Eric Wright” at the song’s beginning, he never strays from that rhyme pattern; it strings together prayers to God and homage to Fredo Santana. This trio of 2020 albums suggests that the windows into an artist’s past, soul, and psyche can be pried open not only in fits of mysterious inspiration, but also by relentless, uniform effort.

0 comments:

Post a Comment