On the first album of a four-part series, the Venezuelan-born, Barcelona-based artist offers her most accessible music to date, channeling her signature sounds into sharply focused avant-pop.

In the overlapping spheres of pop and electronic music—spaces long populated by queer artists moving beyond narrow preconceptions of gender identity—Arca has become one of the most visible figures exploring what it means to transition in public. On KiCk i, the first in a proposed series of four albums, she navigates the spaces in between worlds, languages, genres, and genders. Where her previous releases often felt rooted in melancholy and discomfort, emotions that spilled forth as operatic vocals on 2017’s Arca, KiCk i radiates with self-possessed joy. It contains her most accessible music to date, scooping up her glitchy, slippery textures and chiseling them into hard definition. It’s pop, it’s avant-garde. It’s both and it’s neither.

Opening track “Nonbinary” presents Alejandra Ghersi at her most direct and pop-primed. She’s fierce, self-possessed, in it for the thrill: “I don’t give a fuck what you think/You don’t know me—you might owe me,” she purrs, tasting every syllable. Over clanging pipework and videogame machine guns, she acts out the perverse thrill of doing whatever you want and knowing that someone hates you for it: “What a treat it is to be nonbinary, ma chérie, tee-hee-hee—bitch!”

With each track, Arca applies a different costume—a different skin, even—moving through effervescent electro pop on “Time,” which could be the beginning of a Robyn ballad, and into experimental club rhythms, steamy torch songs, and her own ragged, industrial take on the reggaetón that she encountered as a kid in Caracas. On “KLK,” she and co-producer Cardopusher add extra ballast to a pounding reggaetón production with the growl of the furroco bass drum, a Venezuelan folk instrument that Ghersi learned at school. Elsewhere, the electronic sounds feel familiar enough from the abstract universe of Arca—noises that have no real-world index, but make you think of stuff like latex and metal, volcanic rocks and collapsing buildings—but each element has been sharpened and accentuated.

More than on previous records, Arca bends her voice into multiple shapes and characters. The operatic mode we’ve heard from her before returns on the romantic closer, “No Queda Nada,” and “Calor,” a shuddering love song for her partner: “Eres el dueño de todo mi ser” (“You’re the owner of my whole being”). On “Mequetrefe,” the bashed-up skeleton of a reggaetón rhythm offers an unstable base for her processed voice, which crumbles into metal shards as she imagines herself as a head-turning woman on the hunt for her man: “Ella no toma taxi/Que la vean/Que la vean en las calles” (“She doesn’t take a taxi/Let them see her/Let them see her on the streets”). “Rip the Slit” is also fueled by a combination of shredded reggaetón and treated vocals, this time pitched up to helium-femme proportions.

In addition to Arca’s voices, three female collaborators appear. Shygirl casts a cold glance over “Watch,” dismissing the night’s options in a world-weary Londoner’s monotone: “No feelings, no exclusive.” It doesn’t take much to flip Rosalía’s flamenco tones into something approaching sheer glossolalia, and on “KLK” the bare-bones lyrics are simply a way to generate sound through the Catalan singer’s quivering soprano as she repeats short, scrappy phrases: “Qué es lo que tú crees?” (“What do you think it is?”) and “Bendecida, bendecida” (“Blessed, blessed”).

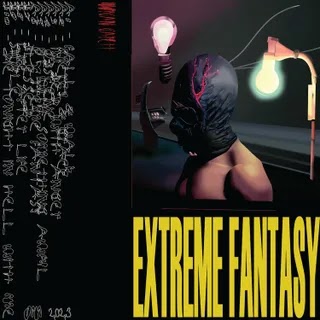

Lacking much of a hook (save for a loop of the Dominican slang phrase “Que lo que”), “KLK” feels more like a studio experiment than a pop song, despite the A-list guest singer. Perhaps that’s the point. Björk appears, singing in Spanish, on “Afterwards,” underscoring the extent to which KiCk i is inspired by the Icelandic musician’s ’90s albums, from the sound—cutting-edge club music combined with pop-facing vocals—to the cyborg cover art, which would surely get the nod from Homogenic art director Alexander McQueen. What Björk once brought to the table, though, was songwriting—image-rich, personal, laden with memorable hooks and emotional landscapes. “Afterwards” has a touch of that (the lyrics are about a dream where “golden bees” make honey “inside my heart”) but the duet slips away like sand between their fingers, never settling on a distinct melody; the song feels restless and unresolved.

The lack of proper songs, for want of a better term, is a mystery. There have never been so many lyrics on an Arca album before, yet, “Nonbinary” aside, they’re mainly used as textural elements rather than vehicles for ideas or stories. This is a shame, as Arca is known for the sharpness and wit she wields in two languages—another duality unpacked on KiCk i, as she flips between English and Spanish. In a recent interview, she made the point that language is prone to “glitches,” misunderstandings that arise when people disagree on the meaning of a given word. “You can have two people arguing about identity politics and gender,” she said, “screaming at each other with both of their faces red, thinking that they’re right.” But the inevitable “glitch” is to be welcomed as a kind of productive dissonance, she added, “because it favors a life that is more unexpected, vibrant and full of possibility. Who doesn’t want that?”

Arca’s music has always incorporated various kinds of glitches, conceptual as much as technological, making electronic ruptures and spasms into her signature sound. Perhaps the same suspicion that meaning is never fixed or certain helps to explain Ghersi’s treatment of voices throughout, as they flicker like radio static, failing to communicate. That will be disappointing for those who were expecting a star-studded pop-crossover album on a par with her guests’ best work. Still, compared to the rest of Arca’s catalogue—including the forbidding twists and turns of @@@@@, the hour-long mixtape from earlier this year—KiCk i marks not only a giant leap towards a bigger audience, but one taken on her own terms.

As she put it in another interview, KiCk i can also be heard as a rallying cry, inviting listeners “to recognize the fact that there’s an alien inside of each of us.” She sets her own inner alien free on the album cover and in other recent images, where she appears almost naked, strapped into prosthetic claws and stilts, or six-breasted, attached to inscrutable devices—a being of her own creation, beyond traditional binaries, part human and part machine. Using the camera and her body to reinvent herself for our (and her) pleasure, Arca joins a long line of musical chameleons. The emancipatory promise of Arca’s project—a world beyond binaries, categories, and convention itself—remains thrilling, even when her tottering steps don’t quite reach that wished-for horizon.

View the original article here

0 comments:

Post a Comment