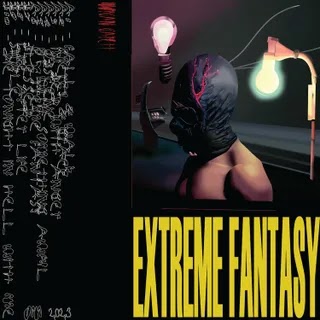

The long-running Belgian avant-garde band explores complicated gender dynamics on their ambitious new double album.

Agenre that defined 1960s French-language pop music, yé-yé always had a glaring gender problem. Named famously after the refrain of “Yeah! Yeah!” that American and British bands introduced to continental Europe, many of the genre’s hits cast teenaged girls as doll-faced puppets for older male songwriters. Certain ’60s artists, most notably the indelible Françoise Hardy, challenged their contemporaries’ misogyny problem, yet yé-yé cast its long shadow on the Francophone mainstream for decades.

On Figures, Belgian avant-garde fixtures Aksak Maboul offer a compelling détournement of French pop’s gender assumptions. Led by Marc Hollander, Maboul emerged in the late 1970s as both globally minded experimenters and malcontents of convention. Their innovative 1980 album Un Peu de l'Âme des Bandits begins with a song called “A Modern Lesson” in which a signature Bo Diddley rhythm—the sort of clavé beat that courses through the bubblegum sounds of the ’60s—dissolves into distorted punk guitar work and discordant samples of Un Peu’s other tracks. The rest of the album thumbs its nose at Western pop, mixing in musical traditions from cultures as varied as Turkey, Polynesia, Baka, and the Mississippi Delta.

After Un Peu, Hollander put Aksak Maboul on the backburner, growing his record label, Crammed Discs, which expounds a highly influential global vision of contemporary sound. He also played in the post-no wave band The Honeymoon Killers, an early collaboration with the singer Véronique Vincent. By the time Aksak Maboul completed their next record, 2014’s Ex-Futur Album, Vincent and Hollander were married and had raised kids together. Musically, she had become frontwoman to his backstage sonic mastermind, a transgressively familiar format they bring to the double album Figures.

At its best, Figures addresses a 21st century in which the misogyny of the 1960s lives on, finding new places to hide and new opportunities to rear its head. One of the few English-language songs, “Dramuscule,” features a parodic conversation between a Georges Perec-reading man and a submissive woman. The man describes himself as the woman’s “hero,” and the woman tells the man, “I drink up your words, and I swallow mine,” before she later leaves him or kills herself—the narrative ends indeterminately. Vincent seems to echo yé-yé tradition on “Spleenétique,” repeating the song’s name at the beginning of each verse in a playful chirp before adding a few nonsense words. Yet the title translates to the English “Splenetic,” and the next lines maintain the rageful momentum coiled beneath her upbeat tone: “Idling speed attack/Ire swells in me.”

The conflict between words and music reflects the album’s gender battles. Though Hollander composed most of the music, Vincent wrote all of the lyrics, and her musings are often self-reflective. “La musique et les lettres,” she sings on a track near the end, her next line translating into English as, “Words have ensnared me.”

While the album’s hour-plus runtime is full of fragments and found sounds, Figures is most cohesive when it serves as a stage for Vincent’s writing. Hollander layers his restless electronic tracks with woodwinds, programmed beats, electric guitar, and runs of jazz piano, but the album lacks the surprising juxtapositions that mark Aksak Maboul’s early work, its relative smoothness often giving the impression that Figures’ arrangements are settings for words and voice.

Non-French speakers may find it difficult to appreciate the quality of Vincent as writer and chanteuse. Of course, listeners across the world are alienated by the tyranny of Anglophone songs, and Aksak Maboul’s musical vocabulary is admirably worldwide. Figures is both musique and lettre, male and female, and it rejects a whole bunch of tyrannies in the course of proving its point.

👉👇You May Also Like👇👌

View the original article here

0 comments:

Post a Comment